Zheng He: An Introduction to the Greatest Navigator in History

On a sweltering July day in 1405, the waters of Longjiang Port in Nanjing shimmered under the summer sun. Along the Yangtze River lay 317 massive ships—floating citadels with masts like forests and sails that blotted out the sky. Aboard them stood 27,800 officers and crew, not as an army of conquest, but as an imperial embassy of goodwill led by the eunuch admiral Zheng He. Their holds carried no cannons, no chains—only silk, porcelain, calendars, and an imperial edict from the Yongle Emperor: “Extend virtuous rule and pacify distant lands with benevolence.”

Fully 87 years before Columbus sketched his imagined route to India on Portuguese maps, Zheng He had already completed the first of seven voyages across the Indian Ocean at the helm of the world’s largest ocean-going fleet. His treasure ships, recorded in the History of Ming as measuring 44 zhang 4 chi (approximately 138 meters), dwarfed Columbus’ flagship Santa Maria (a mere 25 meters) by more than fivefold. Yet what truly set Zheng He apart was this: wherever his fleet sailed, it built not a single colony, forced not one conversion, and plundered not a city’s wealth. Powerful, yet restrained; far-reaching, yet peaceful—this remains a near-unique chapter in the annals of maritime history.

So what made Zheng He unforgettable?

He did not merely redraw trade routes across Asia and Africa—he proved that globalization need not be born of gunboats and greed. Civilizational exchange, he showed, could begin with respect, not fear.

This article invites you into Zheng He’s world—from a boy torn from his home in Yunnan’s highlands to the commander of China’s greatest naval enterprise; from the lantern-lit bazaars of Hormuz to the palm-fringed shores of East Africa where legends of “qilin” still echo. We’ll explore the questions that matter most: How did he achieve all this? What was his greatest legacy? And why did China, after him, turn its back on the sea? Along the way, we’ll dispel myths and recover a vision of global connection too long forgotten.

Chapter 1: From Yunnan Hills to the Imperial Court—A Life Reforged by Fate

In 1371, in Kunyang, Yunnan (modern-day Jinning, Kunming), a Hui Muslim family welcomed a son named Ma He. Both his grandfather and father had made the sacred pilgrimage to Mecca, earning the honorific title Hajji. As a child, Ma He may have recited verses from the Qur’an in the soft dawn light of a mosque—or gazed up at the stars above Dianchi Lake, dreaming beneath the sky of ancient Nanzhao.

But fate shattered when he was just ten. In 1382, Ming forces crushed the last Yuan loyalists in Yunnan. Young Ma He was taken prisoner, castrated—a brutal punishment for the vanquished—and sent to serve in the imperial palace in Nanjing. Overnight, a boy destined to inherit faith and family honor became rootless.

Yet he refused despair. Intelligent and resolute, he was assigned to serve Zhu Di, Prince of Yan. During the Jingnan Rebellion (1399–1402)—the civil war in which Zhu Di seized the throne from his nephew—Ma He fought bravely and advised shrewdly. When Zhu Di ascended as the Yongle Emperor, he rewarded his loyal aide with a new name: Zheng. Thus, Ma He became Zheng He—a rebirth sealed by imperial grace. This bond between ruler and servant was the spark for a grand maritime vision; you can explore the connection between the Forbidden City and the origin of the Ming Treasure Fleet to see how this era began.

Why did the emperor trust him so deeply?

In Ming China, eunuchs—though barred from lineage—could act as the emperor’s direct agents, bypassing the cautious bureaucracy of scholar-officials. Zheng He was rare: a man of military acumen, diplomatic finesse, and cultural duality. A devout Muslim by birth, he also honored Mazu, the Chinese goddess of seafarers. Before each voyage, he burned incense at the Tianfei Temple in Changle, Fujian; in Arab ports, he entered mosques to pray. This was not hypocrisy—it was empathy. And it opened doors from Colombo to Mombasa.

Chapter 2: Seven Voyages, Twenty-Eight Years—A Silent Pilgrimage of Civilizations

To the Ming mind, “the Western Seas” was less a place than a dream—the sapphire expanse of the Indian Ocean, where cloves and ivory flowed, and Islamic minarets rose beside Hindu temples. Between 1405 and 1433, Zheng He led seven expeditions, visiting over 30 polities and sailing more than 160,000 kilometers—enough to circle the Earth four times.

This was no reckless exploration, but a grand strategy of peace.

| Voyage | Years | Key Destinations | Notable Events |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1st | 1405–1407 | Champa, Java, Sumatra, Ceylon | Crushed pirate Chen Zuyi; restored safe passage |

| 2nd | 1407–1409 | Calicut, Cochin | Invested local king with Ming seal and robes |

| 3rd | 1409–1411 | Ceylon | Captured tyrant Alagakkonara; installed a just ruler (attested by the Galle Trilingual Stele) |

| 4th | 1413–1415 | Hormuz | First Ming contact with the Persian Gulf |

| 5th | 1417–1419 | Arabia, East Africa (Kenya, Somalia) | Escorted envoys from 19 nations back to their homelands |

| 6th | 1421–1422 | Southeast Asia, India | Recalled early upon Yongle’s death |

| 7th | 1431–1433 | Hormuz, East Africa | Zheng He died at sea; fleet returned under Wang Jinghong |

He brought back more than goods—he brought wonder.

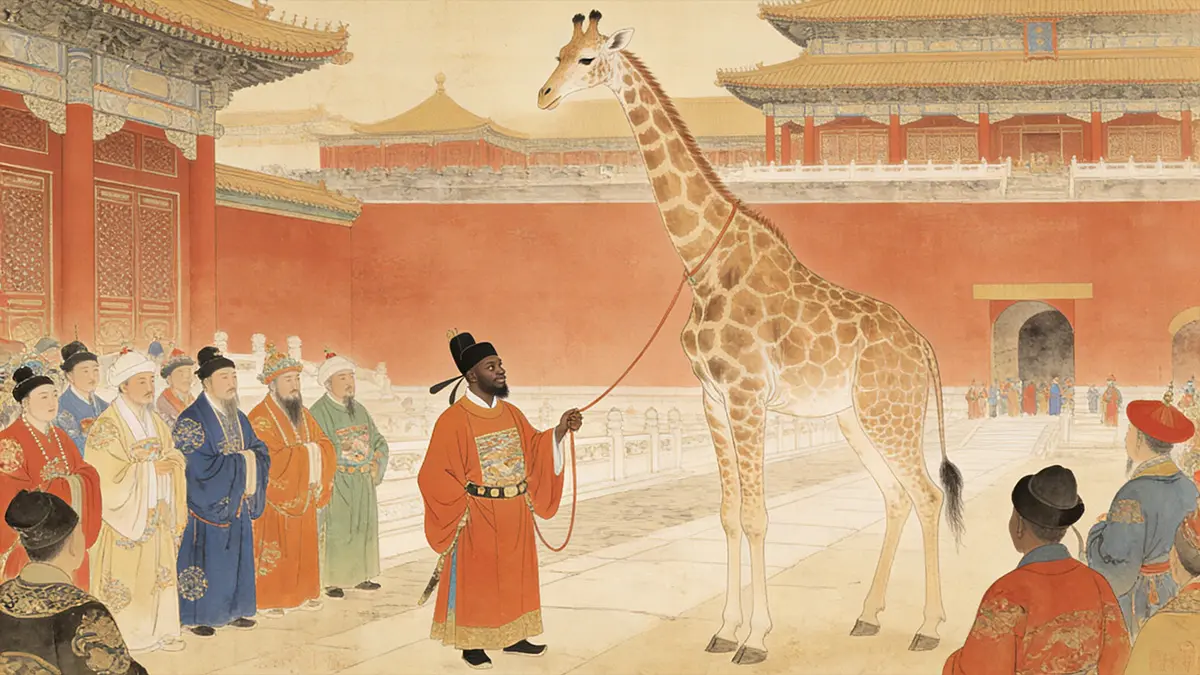

In 1415, after his fifth voyage, a giraffe stepped gently onto Chinese soil. Never seen before in the Middle Kingdom, court scholars pored over ancient texts and declared it the mythical qilin—a celestial omen of sage rule. The emperor commissioned the Illustration of the Auspicious Qilin (now in Taipei’s National Palace Museum), in which the creature bows its long neck as if in reverence. It was a beautiful misunderstanding between two worlds.

Zheng He also returned with zebras, ostriches, frankincense, and African drum rhythms. In turn, China shared silk, porcelain, agricultural techniques, and astronomical knowledge—a true exchange of civilizations.

Chapter 3: The Treasure Ship—A Wooden Leviathan of the 15th Century

“The treasure fleet included 63 great ships,” records the History of Ming, “the largest measuring 44 zhang 4 chi in length and 18 zhang in width.” By Ming standards (1 zhang ≈ 3.11 m), that’s roughly 138 meters long and 56 meters wide—making it among the largest wooden ships ever built.

Skeptics have questioned these figures, but archaeology offers compelling support: in 2003, a rudder shaft 11.07 meters long was unearthed at the Longjiang shipyard in Nanjing. Such a component implies a vessel well over 100 meters in length.

Even more impressive was its engineering:

- Watertight compartments: The hull was divided into independent sections, preventing total flooding—a technology Europe wouldn’t adopt for another 600 years (recognized by UNESCO as intangible cultural heritage in 2008).

- Navigation tools: Compasses guided direction; stellar sighting boards (qianxing ban) measured Polaris’ altitude; hand-drawn rutters charted coastlines.

- Onboard life: Crew grew bean sprouts to prevent scurvy; distillation units turned seawater drinkable; physicians, translators, and astronomers staffed dedicated departments.

This was no floating armada—it was a mobile city of peace.

Chapter 4: The Philosophy of Restraint—When Power Chooses Peace

Zheng He’s true marvel wasn’t his fleet’s size, but its spirit.

He mediated Sumatran civil wars, deposed Ceylonese tyrants, and respected prayer times in every Hormuz mosque. At Galle in Sri Lanka, he erected a trilingual stele—in Chinese, Tamil, and Persian—inscribed with a simple wish: “May all beings be happy; may the land enjoy peace and prosperity.”

His greatest achievement?

Not the treasures he brought home, nor the kings he met—but this: with unmatched naval power, he completed seven global missions without founding a colony, enslaving a soul, or imposing a creed. In human history, such restraint amid strength is almost unparalleled.

Chapter 5: Why Did the Voyages End?—An Empire Turns Inward

Zheng He died during the return of his seventh voyage in 1433. Soon after, the Ming court issued a stark decree: destroy all maritime records, ban construction of large ships, and enforce the policy that “not even a single plank was to touch the sea.”

Four forces drove this retreat, revealing the complex internal and external reasons why China stopped Zheng He’s voyages:

- Financial strain: The voyages cost an estimated 6 million taels of silver—3–5% of the Yongle state’s annual revenue.

- Bureaucratic backlash: Confucian officials condemned the expeditions as “wasteful extravagance” and eunuch-led ventures as “violations of ancestral law.” within the shifting 15th-century Ming Dynasty politics.

- Northern threats: Rising Mongol Oirat power shifted focus to the Great Wall frontier.

- Ideological shift: From cosmopolitan engagement to agrarian conservatism—“valuing grain, restraining commerce.”

An empire that once embraced the ocean chose to forget it.

Chapter 6: Why Zheng He Matters Today—A Model for a Fractured World

In our age, “globalization” often means domination—economic, cultural, military. Zheng He reminds us of another path: one built on reciprocity, not extraction; dialogue, not doctrine.

UNESCO has hailed his voyages as a “model of civilizational dialogue.” In Kenya’s Lamu Archipelago, villagers still speak of “Zheng He’s descendants.” Near Quanzhou’s Qingjing Mosque, Ming-era Arab tombstones stand as silent witnesses to that era of mutual respect.

Five poignant truths about Zheng He:

- A Muslim who lit incense for Mazu—bridging faiths without contradiction.

- Brought a giraffe, revered as a qilin—a tender collision of myth and reality.

- His fleet employed full-time translators, doctors, astronomers, and record-keepers.

- Captured a foreign king—yet replaced him with a just ruler, not a puppet.

- In seven voyages, never stationed a soldier or tax collector abroad.

Epilogue: Rereading Zheng He Is Reimagining Our Future

Zheng He’s greatness lies not in “discovering” new lands, but in refusing to claim them. In an age that glorified conquest, he chose ceremony; in an empire hungry for glory, he practiced humility.

Today, as the world again stands at a crossroads—between coercion and cooperation—we might look back to that summer of 1405 on the Yangtze,A fleet without guns sailed into the unknown blue.

Its commander carried only reverence—and a quiet conviction,“Those who dwell beyond the horizon are human, just as we are.”