Why Did the Yongle Emperor Launch Zheng He’s Voyages?

Eighty-seven years before Columbus set sail, an unprecedented Chinese fleet had already made seven voyages to the Indian Ocean and even the East African coast. Led by the eunuch admiral Zheng He, this fleet boasted nearly 30,000 crew members and vessels stretching up to 140 meters—nearly six times longer than Columbus’ flagship. Yet its purpose was neither to discover new continents nor to establish colonies.

So why did the Yongle Emperor dispatch these maritime expeditions?

Drawing on Ming dynasty official archives, eyewitness accounts, and contemporary international scholarship, this article systematically addresses this question while dispelling a longstanding misconception: Zheng He’s voyages were not a “missed opportunity for globalization,” but rather a meticulously planned imperial strategic operation.

1. Core Motivation: A “Legitimacy Project” to Consolidate Imperial Power

Background: The Anxieties of a Usurper

In 1402, Zhu Di, Prince of Yan, seized the throne from his nephew, the Jianwen Emperor, through a civil war known as the Jingnan Campaign (1399–1402). He then proclaimed himself emperor, adopting the reign title “Yongle” (“Perpetual Joy”). Although he later became one of the most capable rulers of the Ming dynasty, his reign began under a cloud of illegitimacy—Confucian political philosophy emphasized orthodox hereditary succession, and Zhu Di had taken power by force.

As American historian Edward Dreyer notes in Zheng He: China and the Oceans in the Early Ming Dynasty:

“The Yongle Emperor’s most urgent need was not to explore the world, but to prove to both domestic and foreign audiences that ‘Heaven’s Mandate was with him.’”

“All Nations Pay Homage”: Diplomacy as Political Theater

Beginning in 1405, Yongle dispatched his trusted eunuch Zheng He to lead massive fleets on overseas missions. At each port of call—from Malacca to Calicut to Hormuz—grand ceremonies were held. The Chinese distributed silk, porcelain, and copper coins as gifts and invited local rulers to send envoys back to Nanjing to pay tribute.

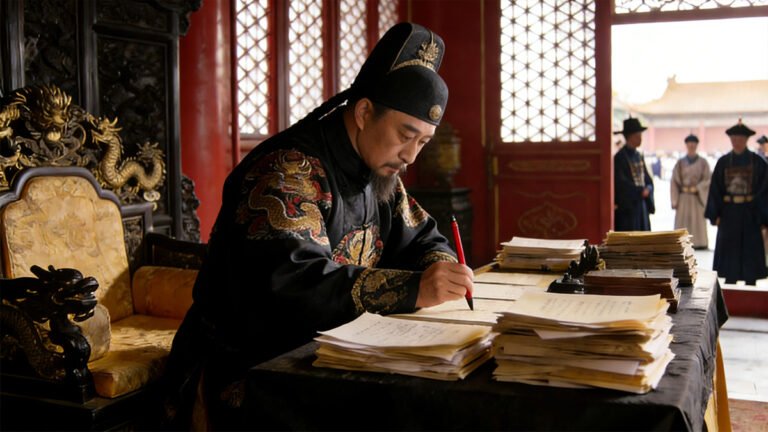

In 1411, envoys from over ten states arrived simultaneously at the Ming capital. Emperor Yongle hosted a grand banquet in the imperial palace, and court painters immortalized the scene as visual proof of universal recognition of Ming authority—a powerful symbol of restored cosmic and political order.

In other words, Zheng He’s primary mission was not trade or exploration, but to reinforce Yongle’s domestic legitimacy by constructing a Ming-centered international order through the tribute system.

2. The Purpose of the First Voyage: Multiple Strategic Objectives

What was the purpose of Zheng He’s first voyage? It was far more than a trial run.

In 1405, two major external threats loomed:

- The Timurid Empire was assembling a massive army in Central Asia, preparing to invade China.

- The Strait of Malacca—a vital maritime corridor—was controlled by the Chinese pirate Chen Zuyi, disrupting tribute traffic.

Cambridge University historian Beatrice Manz confirms in The Rise and Rule of Tamerlane (1989) that Timur died en route to his eastern campaign in 1405. Zheng He’s departure coincided precisely with this moment, strongly suggesting that intelligence-gathering on Central Asian developments was a key objective.

At the same time, in 1407, Zheng He launched a surprise attack at Old Port (present-day Palembang, Indonesia), crushing Chen Zuyi’s pirate network and capturing over 5,000 men. He then established the Old Port Pacification Commission—the first semi-official Chinese administrative presence overseas in history.

Thus, what was the purpose of the seven voyages? Their focus evolved: early missions prioritized security and reconnaissance; later ones emphasized diplomatic prestige and system maintenance.

3. What Tangible Benefits Did China Gain?

Many assume Zheng He brought back vast wealth. In fact, the opposite was true.

According to the Ming Huidian (Collected Statutes of the Ming Dynasty), in 1421 alone the imperial court consumed 120,000 jin of pepper (about 72 metric tons) and 80,000 jin of sappanwood (about 48 metric tons)—almost entirely sourced from tribute missions. Exotic animals also arrived, such as the “qilin” (actually a giraffe) presented by Bangla (modern-day Bangladesh) in 1414.

What three commodities did the Yongle Emperor particularly desire? Historical records point to:

- Pepper (used in medicine and elite cuisine)

- Sappanwood (a red dye also valued in traditional medicine)

- Auspicious exotic animals (like giraffes, interpreted as heavenly signs of virtuous rule)

Crucially, the Ming operated on a “generous giving, modest receiving” principle: the value of imperial gifts far exceeded that of incoming tribute. This was not commerce—it was political investment. The state gained no profit; instead, it spent enormous sums.

So what benefits did China gain from these voyages? Primarily:

- Political prestige (“all under heaven recognize Ming supremacy”)

- Maritime security (pirate suppression)

- Strategic intelligence (on foreign militaries, ports, and religions)

- Diplomatic influence (e.g., supporting the newly founded, pro-Ming kingdom of Malacca)

4. What Happened After the Yongle Emperor’s Death?

What transpired after the Yongle Emperor’s passing? The answer reveals the voyages’ true nature.

Yongle had bypassed the traditional civil bureaucracy by placing naval and foreign affairs under loyal eunuchs like Zheng He. But after his death in 1424, his successors—the Hongxi and Xuande Emperors—restored power to scholar-officials. Finance Minister Xia Yuangji famously protested:

“The treasure ships cost millions annually. How can the people endure such exhaustion?”

By 1433, after the seventh voyage concluded, the Ming court permanently halted oceanic expeditions and reinstated strict maritime prohibitions.

Why did Zheng He’s voyages stop? Not due to technological limits or lost interest—but because of a shift in court politics. The Confucian literati viewed the expeditions as wasteful and ideologically unsound, violating core principles that prioritized agriculture, fiscal restraint, and internal stability over foreign engagement.

5. Zheng He’s Historical Significance: A Practitioner of Peaceful Order

Why is Zheng He important in history?

In an age when empires typically expanded through conquest, Zheng He’s fleet never occupied territory, never established colonies, and never imposed religious conversion. Instead, it sustained a peaceful network of exchange from China to East Africa through gift-giving, ceremonial investiture, and conflict mediation.

As Professor Geoff Wade of the National University of Singapore observes:

“Zheng He’s success depended on the voluntary cooperation of local rulers, not military coercion.”

Thus, what was Zheng He’s significance? He embodied a non-colonial model of global connectivity—one that prioritized mutual recognition over domination. In today’s world, that legacy remains profoundly relevant.