Why Did Eunuchs Have So Much Power in the Ming Dynasty?

The Emperor’s Private Enforcers: How Ming Dynasty Eunuchs Became the “Third Branch” of Government

“Had Machiavelli studied the Ming Dynasty, he would surely have marveled at this cunning design to harness marginalized social groups to counterbalance the elite.”

In modern politics, we are familiar with the “separation of powers”—legislative, executive, and judicial branches balancing one another. But in 16th-century China, Ming emperors faced a more intractable problem: a highly organized bureaucratic elite composed of scholar-officials—a class so entrenched it functioned like what some today call the “deep state.”

To break this monopoly, the emperor did not reform the system. Instead, he created an informal yet efficient “third branch”—not in the American constitutional sense, but as a parallel power center outside the formal bureaucracy: a private administrative and enforcement apparatus run by eunuchs. They were not an “evil accident,” but a carefully engineered mechanism of checks and balances—though one that ultimately spiraled out of control.

You may have heard of the Grand Eunuch of the Office of Ceremonial Affairs, mockingly hailed as the “Nine Thousand Years”—a title just shy of the emperor’s own “Ten Thousand Years”—or of Zheng He, the admiral who led seven epic voyages to the Western Seas. But the true history is far more complex than dramatic portrayals suggest. This article moves beyond cinematic clichés, using institutional logic and rational choice theory to reveal a truth both startling and coherent: Ming eunuchs were not the “source of chaos,” but a mirror reflecting the very essence of absolute imperial power.

Quick Reference: Key Concepts for International Readers

| Chinese Term | Standard English Translation | Western Analogy |

|---|---|---|

| Eunuchs | Eunuchs | Presidential enforcers / inner-circle appointees |

| Scholar-officials | Scholar-officials / Literati | “The Establishment” or tenured bureaucracy |

| Directorate of Ceremonial (司礼监) | Office of Ceremonial Affairs | White House Chief of Staff’s office |

| Grand Secretariat (内阁) | Imperial Cabinet | Policy drafting committee |

| Vermilion Endorsement (批红) | Imperial red-ink approval | Presidential signature on legislation |

| Brocade-Clad Guard (锦衣卫) | Embroidered Uniform Guard | Imperial secret police |

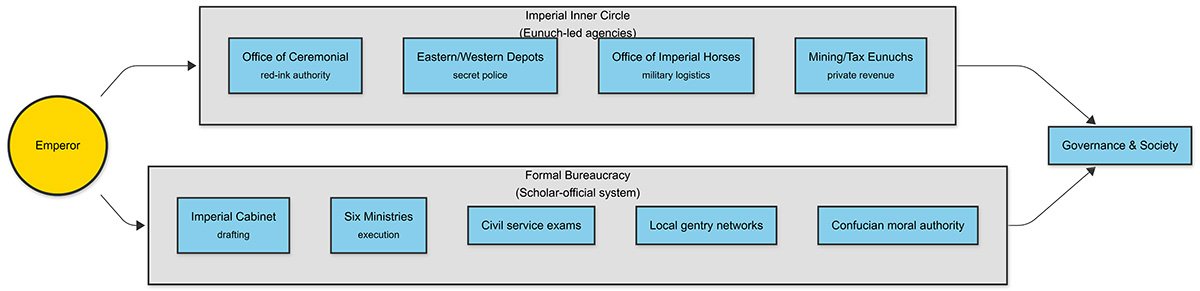

Visualizing Power: The Ming Triangular Structure (c. 1500–1644)

Key Tension: The emperor used eunuchs to bypass the civil bureaucracy and achieve “Vertical Penetration”—a term scholars use to describe direct central control over local affairs. Yet this very strategy fractured the state’s institutional coherence.

1. Institutional Roots: Administrative Expansion vs. Bureaucratic Monopoly

1.1 Zhu Yuanzhang’s Intent vs. Reality

The Ming founder, Zhu Yuanzhang, famously forbade eunuchs from interfering in politics—yet he himself established the Office of Ceremonial Affairs. Initially tasked only with ritual documents, its proximity to the throne turned it into the empire’s nerve center: effectively, the emperor’s “Chief of Staff’s Office.”

1.2 The Xuanzong Reform: The Inner Study Hall (Nei Shu Tang)

In 1425, Emperor Xuanzong founded the Inner Study Hall to teach eunuchs literacy. From then on, they could not only read memorials but also issue vermilion endorsements—the emperor’s red-ink approval that gave policies legal force.

Imagine this: the Imperial Cabinet drafts a policy, but a group of castrated men—socially despised yet institutionally indispensable—hold the vermilion pen. Without their stroke, even the wisest proposal remains dead paper.

This “war at the tip of the pen” defined Ming power dynamics for two centuries.

2. Why Eunuchs? An Extreme Loyalty Mechanism

In imperial China’s political logic, castration was not humiliation but a biopolitical guarantee of loyalty:

- Civil officials had families, regional ties, and factional interests;

- Eunuchs had no descendants, no exit, and total dependence on the throne—making them ideal “lonely loyalists.”

More crucially, scholar-officials saw themselves as moral guardians of Confucian orthodoxy. They resisted “immoral” acts like arbitrary taxation or secret arrests—not out of incompetence, but principle.

This created a classic institutional divide:

- Scholar-officials ≈ The Establishment: A tenured bureaucracy controlling policy execution, local governance, and ideological legitimacy.

- Eunuchs ≈ Political Appointees / Inner Circle: Temporary, personally loyal agents empowered to bypass the system and execute the emperor’s will directly.

This “outsider agents vs. insider establishment” conflict mirrors contemporary Western politics—from Trump’s battles with the “deep state” to Brexit’s revolt against Brussels technocrats. The Ming simply pushed this logic to its extreme.

Faced with a dilemma—how to enforce unpopular measures without tarnishing his “benevolent ruler” image—the emperor turned to eunuchs as agents for dirty work: unburdened by ethics, indifferent to posterity, loyal only to him.

Emperor Jiajing put it bluntly:

“Outer-court ministers form cliques for gain; though lowly, my eunuchs obey only me.”

This was no Chinese oddity:

- Byzantium placed its navy under eunuch command;

- Ottoman harem eunuchs wielded power surpassing viziers;

- Machiavelli advised: “A prince should employ those who have no other recourse.”

As Canadian sinologist Timothy Brook writes in The Confusions of Pleasure:

“The rise of eunuchs was not corruption, but the center’s attempt to penetrate local gentry networks and reassert direct rule. Their failure exposed the core tension between centralization and governability in imperial states.”

The Emperor’s “Gilded Cage”: Rule Under Information Asymmetry

Western readers often ask: If the emperor held absolute power, why not govern personally?

The answer: he was trapped in the Forbidden City—his “gilded cage.”

He couldn’t travel incognito, meet commoners, or even leave the palace freely. All intelligence—on famines, corruption, or mutinies—came filtered through intermediaries.

And the bureaucracy had every incentive to sanitize bad news to preserve stability—or their own careers.

Thus, eunuchs became the emperor’s “eyes and ears.” They spied on ministries, inspected provinces as tax envoys, and arrested officials without trial.

This wasn’t laziness—it was the only way to govern under extreme information asymmetry.

3. The Ultimate Gamble: Self-Castration as an “Extreme Career Pivot”

To Western eyes, self-castration seems like madness. But in rigid Confucian society, a man who failed the exams faced locked-in social status: no land, no voice, no future.

Here, self-castration became a rational, high-stakes gamble—an “extreme career pivot,” akin to quitting a safe job to launch a Silicon Valley startup: near-certain failure, but success meant generational transformation.

This aligns perfectly with Rational Choice Theory: when the conventional path (exams) offers near-zero odds, and the alternative (palace service)—though physically costly—offers the only escape, a rational actor chooses the latter.

Like Europe’s castrati singers—boys altered to preserve angelic voices for church and court—Ming aspirants traded bodily integrity for social ascent.

The payoff? Staggering:

- A North China farmer earned 1–2 taels of silver/year—bare subsistence;

- A mid-level eunuch (e.g., Document Office clerk) drew only 30 taels in salary, but accessed silk, spices, porcelain, and overseas luxuries through gifts and off-the-books income—wealth rivaling a county magistrate.

Even better: he could exempt his entire family from forced labor, and send his children to the Imperial Academy—privileges ordinary families couldn’t dream of in ten lifetimes.

As one father told his son before sending him to the palace:

“Better to sever a finger than live in poverty for a lifetime.”

Under systemic exclusion, bodily sacrifice became the ultimate rational investment.

4. The Power Pyramid: 99% Were Invisible

Thousands self-castrated, but most remained menial palace laborers (“xiao huo zhe”). Real power required:

- Graduation from the Inner Study Hall;

- Appointment to core agencies like the Office of Ceremonial or Office of Imperial Horses.

Per eunuch Liu Ruoyu’s Zhuozhong Zhi, the hierarchy was strict:

Chief Seal Keeper → Scribal Keeper → Attendant Keeper → Clerk → Laborer

Whoever sat in the top seat became a functional tool—replaceable, disposable, inevitable.

5. Icons Reconsidered: System Over Individual

5.1 Zheng He: Navigator and Narrator

Zheng He didn’t just sail—he authored texts like Yingya Shenglan to frame Ming voyages as peaceful diplomacy. Recent tomb inscriptions show elite eunuchs actively crafting legacies of “loyalty, diligence, prudence.”

This reminds us: the “eunuch = villain” trope stems largely from Donglin Party historiography—the winners’ narrative.

5.2 Wei Zhongxian: A “Functional Necessity”

The Tianqi-era Chief Eunuch (later vilified as “Wei Zhongxian”) wasn’t a monster—but a functional necessity. The emperor needed someone to collect taxes, crush dissent, and spy on officials—tasks Confucian elites refused, and imperial kin might exploit to seize power.

This is a textbook agency problem: the principal (emperor) hires an agent (eunuch) for dirty work, then sacrifices him to preserve legitimacy when backlash comes.

No matter who held the seal, the system demanded a Wei Zhongxian.

His fate encapsulates the eunuch’s role: the emperor’s blade—sharp, useful, and discarded once bloodied.

6. Global Parallels: The Eastern Depot and the Star Chamber

Founded in 1420, the Eastern Depot—led by eunuchs—could arrest, torture, and execute without trial, surpassing even the Embroidered Uniform Guard in reach.

For British readers, it resembled the Tudor Star Chamber: a secret tribunal bypassing common law to enforce royal will. But while the Star Chamber seated nobles, the Eastern Depot was run by a castrated peasant—highlighting Ming reliance on society’s ultimate outsiders.

As Harvard’s Fairbank Center notes:

“Eunuch dominance was the product of intense conflict between centralized monarchy and mature bureaucracy—yet it followed universal logics of imperial rule.”

7. Collapse and Legacy

When Chongzhen executed the last Chief Eunuch and returned power to scholar-officials, factionalism worsened. The flaw wasn’t individuals—it was institutional imbalance.

The Qing learned fast: they banned eunuch politics and replaced the Office of Ceremonial with the Imperial Household Department—a civilian-controlled agency. The “third branch” was permanently retired.

Ming eunuchs reveal not decadence, but the tragic logic of absolute rule: when you can trust no one, you empower those who have nothing to lose—and everything to gain from your survival.

Today, as we view Zheng He’s ship models at the National Museum of China or the rusted “Eunuchs Shall Not Interfere in Politics” plaque in the Forbidden City, we should ask not “How evil were they?” but:

What does a system look like when it must rely on the mutilated to guard its soul?

And in the silence of the unnamed—those who swept floors, guarded gates, or died nameless on the road to the palace—we hear the empire’s deepest echo.

Appendix: For the Global Reader

📚 Sinological Perspectives

- Ray Huang: 1587, A Year of No Significance – argues Ming governance substituted morality for technical capacity.

- Timothy Brook: The Confusions of Pleasure – frames eunuchs as tools of vertical penetration.

- Evelyn Rawski: The Last Emperors – contrasts Ming reliance on eunuchs with Qing institutional restraint.

References:

- History of the Ming Dynasty. Zhonghua Book Company.

- Huang, Ray. 1587, A Year of No Significance. Yale University Press.

- Brook, Timothy. The Confusions of Pleasure: Commerce and Culture in Ming China. University of California Press.

- Cai, Shishan. The Eunuchs in the Ming Dynasty. Cambridge University Press.

- National Museum of China (English): www.chnmuseum.cn/en