Zheng He’s Leadership: How a Resilient Personality Led the World’s Largest Fleet

At the age of ten, he was captured amid the war in Yunnan, castrated, and forced into the palace. Physically mutilated and stripped of his identity, he might have been destined for a life of insignificance. Yet he rose from the ashes to become the most formidable naval commander of the 15th century—commanding a super fleet sixty times larger than Columbus’s fleet, crossing the Indian Ocean seven times, and reaching as far as East Africa. His treasure ships resembled 15th-century aircraft carriers, their decks spacious enough to hold four Santa Marias. Commanding 28,000 elite troops, he never colonized an inch of land nor forced a single conversion. As a Muslim, he revered Buddhist statues; as a eunuch (in reality the empire’s chief advisor and admiral), he spearheaded the Ming Dynasty’s “United Nations”-style soft power diplomacy. His story is a true underdog tale: from slave to giant, from ruins to the seas, connecting half the world through restraint and empathy.

In 1405, a fleet comprising 62 giant ships and 208 support vessels set sail from Fujian, China, carrying nearly 28,000 officers and soldiers—one of the largest ocean-going fleets in human history. Its commander was not a general, but a eunuch named Zheng He—more accurately, the Yongle Emperor’s “Imperial Chief of Staff” and “Grand Admiral of the Ming Navy.”

Over the next 28 years, he crossed the Indian Ocean seven times, reaching as far as the East African coast, yet never occupied an inch of land nor forced any nation to convert or pay tribute.

This was exceptionally rare in the 15th-century world.

So what made Zheng He’s voyages so extraordinary? The answer lay not in the size of his treasure ships, but in his character: a leadership style blending cross-cultural empathy, crisis composure, organizational rationality, and diplomatic restraint.

To understand this leadership, we must begin with the dawn that changed his life forever.

1: From Slave to Giant: A “Phoenix in a Disabled Body”

In 1371, Ma He was born into a Hui Muslim family in Kunyang, Yunnan. His father had made the pilgrimage to Mecca, and Arabic scriptures hung on the walls of their home. At age ten, Ming forces overran Kunming, reducing his home to ashes. Dragged from the corpses, he was castrated and sent to the palace—his body was destroyed, his name stripped away, and his path home severed.

In Western culture, “eunuch” often conjures Varys from Game of Thrones: cunning, marginalized, disdained. Zheng He’s story diverges sharply. He was no schemer, but a leader reborn from the flames—a “giant in a broken body.”

He did not succumb to trauma. Instead, he studied Chinese language, military strategy, and diplomacy with relentless dedication at the Prince of Yan’s residence in Beiping. During Zhu Di’s coup d’état, the Jingnan Campaign, he charged into battle and earned military honors. After Emperor Yongle ascended the throne, he bestowed upon Zheng the imperial surname “Zheng” and appointed him Chief Eunuch of the Palace Bureau—not a menial position, but equivalent to today’s “Imperial Chief of Staff,” directly overseeing diplomatic and military operations.

From prisoner of war to supreme commander, his rise was a phoenix-like rebirth. Yet the stage for this remarkable comeback was not the palace, but the turbulent seas thousands of miles away.

2: The Aircraft Carriers of the 15th Century: The Largest Peace Fleet in History

Winter 1405, Changle Port, Fujian. Zheng He’s fleet stood ready for departure:

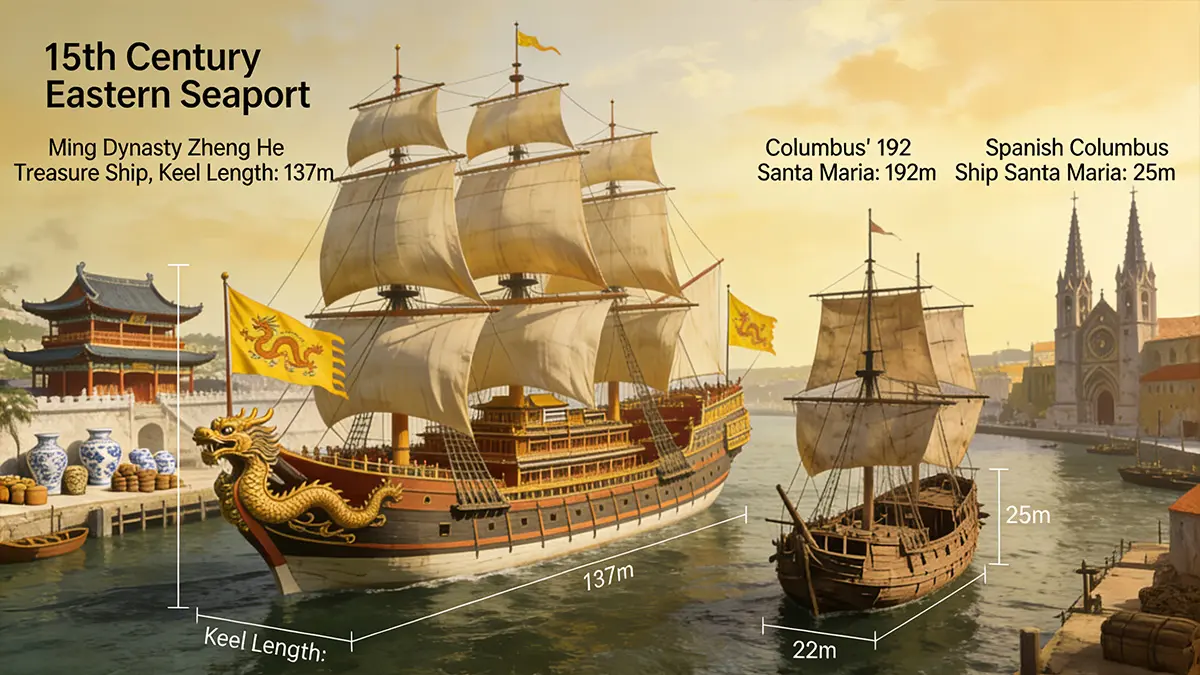

- 62 Treasure Ships—each measuring approximately 120–137 meters in length, equivalent to 15th-century aircraft carriers

- 208 auxiliary vessels (for transporting troops, provisions, medical supplies, and warships)

- Nearly 28,000 personnel: soldiers, physicians, interpreters, astronomers, artisans, and monks

The deck of a single Treasure Ship alone could hold four of Columbus’s Santa Marias; the entire fleet’s scale exceeded Columbus’s expedition by over sixtyfold.

Yet this “super fleet” was not sent to conquer, but to connect.

3: Interfaith Diplomacy: The Inclusive Wisdom of a Muslim Admiral

Zheng He was a Muslim—a 1413 stele in Quanzhou explicitly records him “visiting the mosque to burn incense.”

He also funded the construction of Buddhist temples, such as the Hongjue Temple on Niu Shou Mountain in Nanjing. In Ceylon (present-day Sri Lanka), he left a trilingual stele (Chinese, Tamil, Persian) while simultaneously dedicating Buddhist statues, Shiva idols, and the Kalima—this artifact, now housed in the National Museum of Colombo, stands as a rare 15th-century masterpiece of interfaith diplomacy.

In Java (present-day Indonesia) and Calicut (present-day Kerala, India), he respected local customs and supported religious pluralism. The result? Over thirty nations voluntarily joined the Ming dynasty’s tribute system—not as vassals, but as members of a Ming-style United Nations: each state retained sovereignty while exchanging ceremonial tributes for trade privileges and security guarantees.

4: An Anchor in the Storm

Zheng He was not solely a man of peace. In 1407, he ambushed pirates led by Chen Zuyi at the port of Cikarang (present-day Palembang, Indonesia), annihilating over five thousand men and capturing their leader alive to be executed in Nanjing.

Yet when confronting natural disasters, he displayed remarkable composure. Crew member Ma Huan recorded: “A hurricane suddenly struck, with waves soaring thirty feet high. All cried out in terror. The Admiral sat calmly in his cabin, ordering each ship to steady the rudder according to the Compass Manual.” The Compass Manual served as a standardized navigation handbook—the 15th-century equivalent of a standard operating procedure (SOP). This institutionalized management ensured none of the seven voyages suffered catastrophic failure.

5: Maritime City-States: The Most Complex Transnational Project in History

Zheng He’s fleet functioned as a floating city:

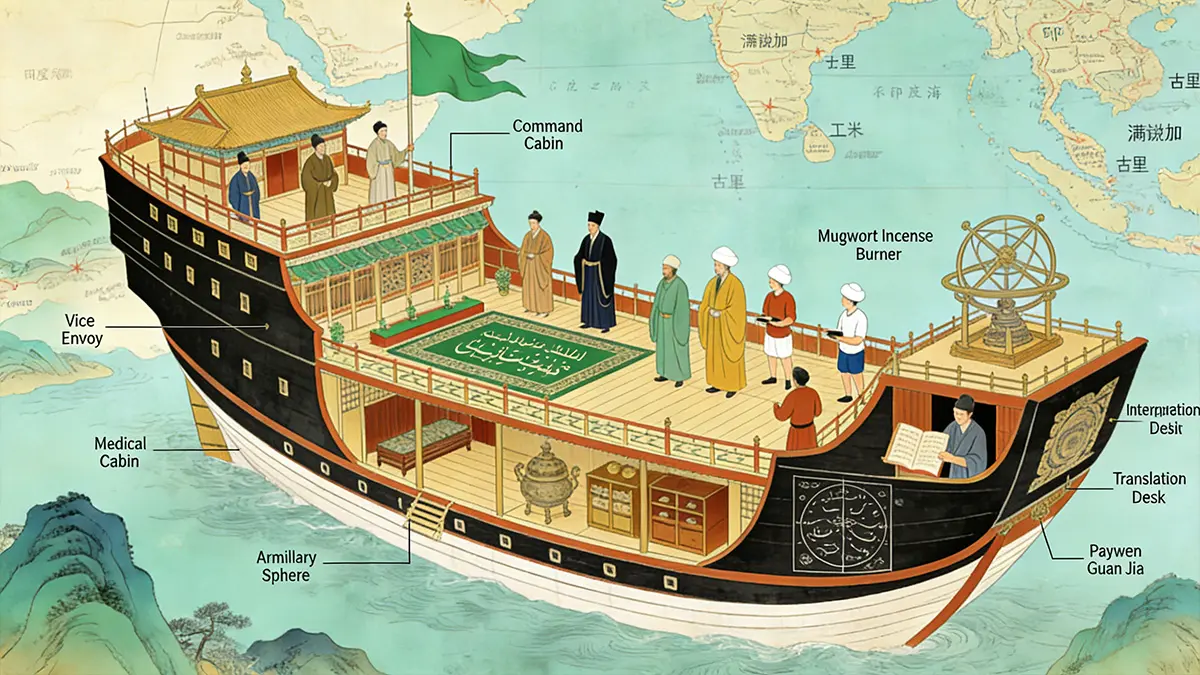

- Chief and Deputy Envoys: Fleet Commanders

- Navigators: Charting courses using compasses and celestial charts

- Interpreter: Translator (fluent in Arabic, Malay, etc.)

- Medical Officer: Fumigated cabins with mugwort for disease prevention

- Astrologer: Observed celestial phenomena to determine course

The ships featured Muslim prayer areas (marked by green flags), while Buddhist monks presided over Mazu worship ceremonies. This seamless collaboration among diverse teams represented an exceptionally inclusive management system rare in the pre-modern world.

6: Why Not Colonize? The Classical Practice of “Soft Power Strategy”

Western readers often ask: With such a powerful navy at his disposal, why didn’t he establish colonies?

Because the Ming Dynasty’s goal was not plunder, but “spreading virtue”—that is, exporting the imperial brand (Brand Awareness of the Empire). The fleets carried silk and porcelain as gifts, seeking only symbolic “tribute” from foreign rulers.

As he declared after repelling Siamese invaders at Malacca (present-day Malaysia): “I serve the Son of Heaven to spread virtue, not to seize territory.”

This strategy of “giving generously and receiving sparingly”—trading short-term costs for long-term influence—is a classic example of soft power strategy.

7: The Final Voyage: The 61-Year-Old’s Final Promise

After the Yongle Emperor’s death in 1424, the maritime expeditions were halted. Zheng He was reassigned to guard Nanjing, where he remained for nine years.

In 1431, at the age of 61 (born 1371), he insisted on embarking on a seventh voyage. Before departure, he erected the Stele Commemorating the Divine Response of the Heavenly Consort in Changle, Fujian, inscribing: “…to propagate virtue and win over distant peoples.”

His tone was calm, yet it felt like a farewell. For him, this voyage was perhaps no longer merely fulfilling orders, but completing a personal mission spanning three decades.

Two years later, he died of illness in Calicut (present-day southern India). His remains were returned to Nanjing for burial, but his influence lingered in distant lands—Ming Dynasty porcelain unearthed in Kenya and the legend of “Lord Sanbao” passed down in Java stand as enduring testaments to this era of peaceful exchange.

Zheng He vs. Columbus: Two Beginnings of Globalization

| Dimension | Zheng He (1405–1433) | Columbus (from 1492 onward) |

|---|---|---|

| Objective | Build prestige and peaceful networks | Seek gold and spread Christianity |

| Methods | Gifts, diplomacy, and limited use of force | Conquest, enslavement, and colonization |

| Fleet Nature | State-sponsored “peace fleet” | Privately funded “expedition” |

| Long-term Impact | Cultural exchange | Colonial empires |

Zheng He’s voyages abruptly ceased after 1433. Yet his legacy proved this truth: true strength lies not in how many you can conquer, but in how many willingly draw near to you.

References:

- History of the Ming Dynasty, Vol. 304: Eunuchs I (Zhonghua Book Company annotated edition)

- Ma Huan, A Survey of the Ocean’s Shores (National Library of China digital collection)

- Edward L. Dreyer, Zheng He: China and the Oceans in the Early Ming Dynasty (Cambridge University Press, 2007)

- Quanzhou Maritime Museum Official Website: www.qzsm.org.cn

- National Maritime Museum, UK: www.rmg.co.uk

- Galle Trilingual Stele, Colombo National Museum