The Forbidden City and the Treasure Fleet: The Origin of World-Leading Naval Power

What connection does the Forbidden City have with the Ming Dynasty navy?The Forbidden City was not merely the emperor’s residence but the strategic command center of the world’s most powerful navy in the 15th century. From within its walls, the Yongle Emperor ordered the construction of the Treasure Fleet and appointed Zheng He—a Muslim eunuch who served in the imperial court—to lead seven transoceanic voyages. Mobilizing the state’s fiscal, administrative, and industrial resources, this fleet enabled the Ming Dynasty to dominate Indian Ocean trade and diplomacy decades before European powers entered the region. The rise—and abrupt disappearance—of this naval superpower hinged entirely on a single decree issued from the imperial palace in Beijing.

Why Is the Forbidden City Called the “Naval Headquarters”?

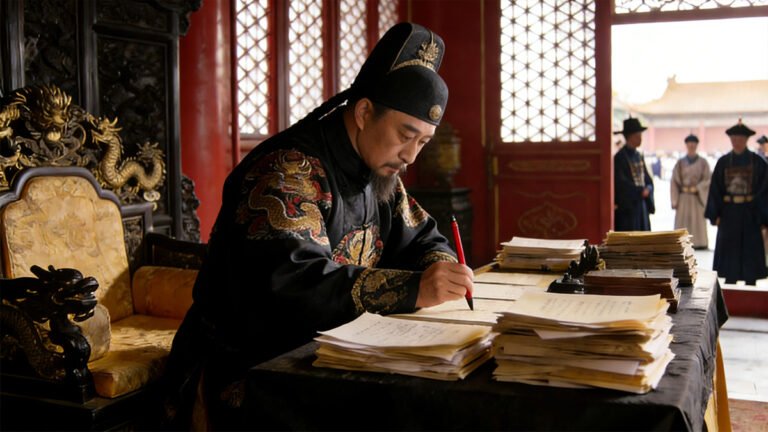

To many Western readers, “imperial palace” and “navy” may seem unrelated. Yet in Ming China, the Forbidden City was the physical embodiment of centralized state power. In 1406, the Yongle Emperor moved the capital to Beijing and began constructing the Forbidden City—not only to assert legitimacy after usurping the throne but also to create a highly efficient command system. Major military and diplomatic operations, including Zheng He’s voyages to the “Western Seas,” were directly ordered by the emperor from the Hall of Supreme Harmony or the Palace of Heavenly Purity, bypassing the regular civil bureaucracy.

Crucially, the treasure ships were neither built nor commissioned locally.

As recorded in Volume 24 of the Veritable Records of the Ming Taizong:

“The eunuch Zheng He was commanded… to go and instruct the nations of the Western Ocean, and to have sea vessels constructed at the Longjiang Shipyard Office.”

This reveals a clear operational structure:

- Decision-making center: The Forbidden City, Beijing

- Execution sites: Longjiang Shipyard (Nanjing) and Changle Port (Fujian)

- Command chain: Emperor → Imperial Eunuchs (Office of Eunuchs) → Ministry of Works / Ministry of War

Archival records from the Palace Museum indicate that the Longjiang Shipyard alone employed over 10,000 craftsmen and could produce dozens of large ocean-going vessels annually (Source: The Palace Museum – Ming Shipbuilding). This “central directive, local execution” model exemplified the Ming state’s formidable capacity for large-scale coordination.

In short: without the will of the Forbidden City, there would have been no Treasure Fleet.

The Treasure Fleet: A “Super Fleet” Decades Before Columbus

Zheng He is often called “China’s Columbus,” but this comparison obscures more than it reveals:

| Feature | Zheng He’s First Voyage (1405) | Columbus’s First Voyage (1492) |

|---|---|---|

| Number of ships | 62 treasure ships + 208 support vessels | 3 small caravels |

| Crew size | ~27,800 men | ~90 men |

| Largest ship length | ~137 meters (per Ming Shi) | ~25 meters |

| Armament | Lightly armed; focused on diplomacy | Heavily armed; colonial intent |

| Mission | “To display virtue and pacify distant peoples” (xuande hua er rou yuanren) | Find a western route to Asia for trade and conquest |

The technological sophistication of the treasure ships was equally remarkable. They featured watertight bulkheads—compartments sealed off from one another so that damage to one section wouldn’t sink the entire vessel. This innovation predated similar European designs by at least 500 years and was inscribed on UNESCO’s Representative List of the Intangible Cultural Heritage of Humanity in 2010 (UNESCO, “Watertight Bulkhead Technology of Chinese Junks”).

Even more telling was the fleet’s composition: it carried medical officers, interpreters, astronomers, clerks, and even floating vegetable gardens to ensure fresh food. This was not a conquering armada but a mobile imperial embassy—a floating network of diplomacy, trade, and intelligence that engaged over 30 polities across Southeast Asia, India, the Persian Gulf, and East Africa.

But how was such an immense enterprise sustained?

How Did the State Fund the Voyages?

Scholar Louise Levathes estimates that the seven voyages cost several million taels of silver—roughly 10–15% of the Ming Dynasty’s annual fiscal revenue (When China Ruled the Seas, Oxford University Press, 1994). Funding came from three main sources:

- The Imperial Treasury (Taicang) – Central government reserves

- Maritime Trade Superintendencies (Shibosi) – Customs offices collecting tariffs on foreign trade

- Tribute-trade profits – Foreign envoys brought spices, ivory, and exotic goods; the Ming reciprocated with silk and porcelain. Though framed as “giving generously and receiving modestly,” this system allowed the court to monopolize high-value commodities and gather strategic intelligence.

Personnel structure was equally critical. As a senior eunuch of the Office of Eunuchs, Zheng He reported directly to the emperor and operated outside the control of the civil bureaucracy. This allowed the Forbidden City to bypass red tape and mobilize resources swiftly. In 1412, for instance, the Yongle Emperor authorized the construction of the Tianfei Palace in Changle, Fujian, and erected a commemorative stele that reads:

“Imperial Eunuch Zheng He… commanded tens of thousands of officers and soldiers, sailing forty-eight ocean-going vessels to various foreign nations.”

(The stele is now housed in the National Museum of China.)

Yet this very strength—dependence on imperial will—became the fleet’s fatal weakness.

1433: Why Did the World’s Mightiest Navy Vanish?

After the Yongle Emperor’s death in 1424, policy shifted dramatically. His son, the Hongxi Emperor, immediately issued an edict:

“Cease the voyages to the Western Seas and order all coastal regions to focus on fortifying defenses.”

(Veritable Records of the Hongxi Emperor)

Although the Xuande Emperor permitted one final voyage in 1431, the fleet never sailed again after Zheng He’s return in 1433.

The decline had nothing to do with technological incapacity. Later Ming admirals like Qi Jiguang still deployed advanced warships (e.g., Fuchuan vessels with cannons) during anti-piracy campaigns, and Ming fleets blockaded Korean waters during the Imjin War (1592–1598). The real cause was political:

- The civil official faction regained influence and condemned the voyages as “wasteful extravagance” (xuhao guokuang)

- Rising Mongol threats along the northern frontier redirected military priorities inland

- The court enforced a strict maritime prohibition: “Not even a single plank is permitted to go to sea” (pian ban bu xu xia hai, Great Ming Code)—effectively severing civilian maritime tradition

Technology endured, but the institutional framework collapsed. A navy that had led the world for nearly a century vanished not with a battle, but with a bureaucratic memo from the Forbidden City.

A Different Globalization?

Today, archaeologists on Kenya’s Lamu Archipelago have uncovered Ming-era porcelain and DNA evidence suggesting descendants of Chinese sailors may have settled there (BBC News, 2020). In Indonesia and Malaysia, Zheng He—known locally as “Sam Po Kong” or “Lord Sanbao”—is still venerated in temples. These fragments hint at an alternative path: a globalization rooted in diplomacy, tribute, and cultural exchange, not colonization or extraction.

But history has no “what ifs.” As Joseph Needham famously asked in Science and Civilisation in China:

“Why did modern science not develop in China despite its early technological lead?”

The fate of the Treasure Fleet embodies the “Needham Question”: innovation alone is not enough. Without sustained institutional support, strategic continuity, and openness to the sea, even the most advanced capabilities fade into legend.

In 2025, as the world marks the 620th anniversary of Zheng He’s first voyage, the lesson remains urgent: a nation’s maritime ambition lies not in the size of its ships, but in whether its leaders are willing to sustain a long-term commitment to the oceans beyond their shores.

References

Primary Sources:

- Ming Shilu (Veritable Records of the Ming Dynasty), Zhonghua Book Company

- Ma Huan, Yingya Shenglan (The Overall Survey of the Ocean’s Shores), 1416, Harvard-Yenching Library

Scholarly Works:

- Levathes, Louise. When China Ruled the Seas. Oxford University Press, 1994.

- Needham, Joseph. Science and Civilisation in China, Vol. 4: Physics and Physical Technology – Part 3: Civil Engineering and Nautics. Cambridge University Press.

Institutional Sources:

- The Palace Museum (Beijing): Ming Dynasty Administrative System

- UNESCO: “Watertight Bulkhead Technology of Chinese Junks” (2010)

- BBC News: “Chinese Descendants Found in Kenya?” (2020)

Verified Encyclopedic Entries:

- Wikipedia: “Zheng He,” “Ming treasure voyages,” “Forbidden City” (cross-checked against academic sources)