Ming Dynasty vs. Europe: The Advanced Anchor and Rudder Tech of Treasure Ships

In 1405, when Zheng He’s flagship sailed out of the Yangtze River estuary, its rudder stock measured 11.07 meters—longer than half the entire length of Columbus’s Santa Maria (approximately 18.9 meters) 87 years later¹. According to the History of the Ming Dynasty, this treasure ship was about 44 zhang (approximately 137–150 meters) in length. While academic debate persists over whether all-wooden structures could physically support such lengths², even conservative estimates of 60–80 meters (equivalent to 3–4 Santa Marias end-to-end) demonstrate that the technical logic behind its rudder and anchor represented the pinnacle of 15th-century global maritime engineering.For those seeking to understand the full scale and history of these vessels, this comprehensive guide to Ming treasure ships provides a deep dive into their construction and legacy.

In an era without hydraulics or steel keels, how did the Chinese steer a massive ocean-going flagship with a purely wooden structure? The answer lies in two long-overlooked inventions: the balanced rudder.

To grasp this technological gap, we must first examine what Europe was using during the same period.

While Europe was still steering with ropes, the Ming Dynasty was already harnessing fluid dynamics to save effort.

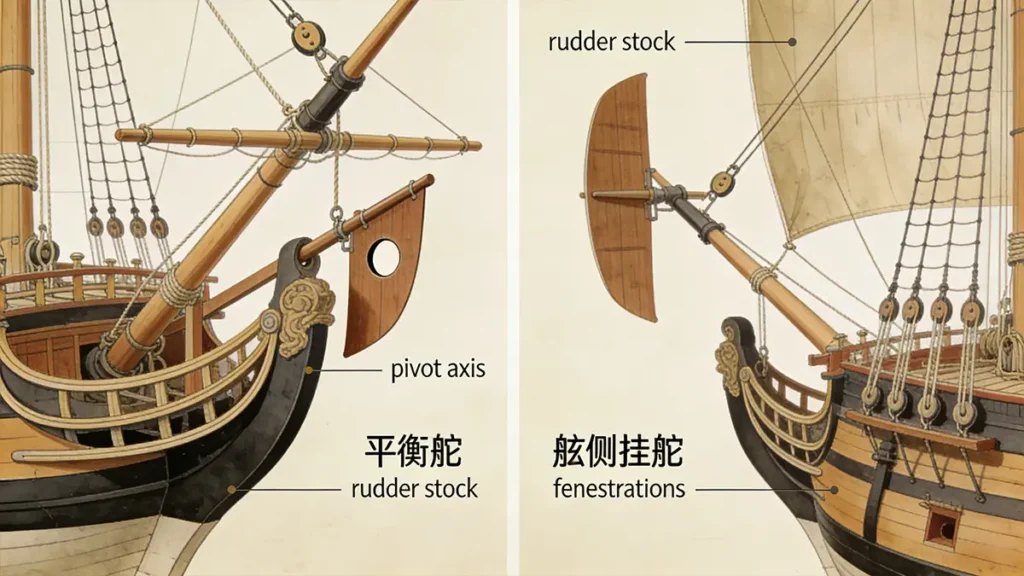

In the early 15th century, Europe’s largest ocean-going vessels—such as carracks and early caravels—still relied on side-hung rudders, typically secured by pintle-and-gudgeon fittings. This rudder type was fixed to the starboard side of the stern, with the entire rudder blade positioned behind the pivot axis. To steer, sailors had to pull ropes or tiller handles with all their strength, fighting against the water resistance across the entire rudder surface—like trying to push a door open against a hurricane.

In contrast, Ming Dynasty treasure ships employed balanced rudders with a forward-shifted pivot axis. The key difference lay in the rudder stock: instead of being positioned at the very front of the blade, it was shifted forward, placing part of the leading edge ahead of the pivot point. When water struck the rudder surface, the pressure generated at the leading edge automatically counteracted the resistance at the trailing edge, drastically reducing the manpower required for steering.

Modern fluid dynamics simulations show this design reduces steering torque by over 30%. For a massive ocean-going vessel requiring frequent course adjustments, this meant less fatigue, quicker responses, and lower operational risks.

The giant rudder stock unearthed at the Nanjing Longjiang Shipyard site stands as physical proof of this system. Crafted from a single piece of nanmu wood, this rudder stock measures 11.07 meters long with a diameter of nearly 1 meter and is now housed in the National Museum of China⁵.

So, does the rudder blade itself incorporate further ingenuity? Indeed it does—and while it may appear to be a “shortcut,” it actually represents a brilliant application of ancient fluid dynamics.

The Tiny Holes on the Rudder Blade Are Actually Cutting-Edge Drag-Reduction Technology

If you examine a reconstruction of a Ming Dynasty treasure ship’s rudder, you might notice a peculiar detail: a row of small circular holes drilled into the rudder blade. Early Western researchers mistakenly attributed these to rot. However, Joseph Needham pointed out in his Science and Civilisation in China that this was an intentional design feature, known as a “fenestrated rudder.”⁶

The principle is straightforward: during high-speed navigation, water flowing around a solid rudder blade creates vortices behind it, generating vibrations and additional drag. The small holes allow some water to pass through, disrupting the vortex structure and achieving turbulence reduction. This stabilizes steering efficiency and lowers energy consumption. The design also effectively mitigates the risk of hydrodynamic cavitation at high speeds.

A 2020 CFD (Computational Fluid Dynamics) simulation by Shanghai Jiao Tong University confirmed that the perforated design reduces drag by 15–20%, with particularly superior performance in cross-sea conditions⁷.

By contrast, Europe did not begin experimenting with similar drag-reducing structures on rudders until the 18th century. Yet Ming Dynasty craftsmen had already transformed empirical intuition into functional design as early as the 1400s.

However, even the finest rudder requires a reliable mooring system. Without it, a giant vessel in the Indian Ocean monsoon is nothing more than a death trap adrift.

Four-Fluked Iron-Bound Anchor: The Sea’s Anchor in the Deep

The anchors aboard treasure ships also defied conventional wisdom. Archaeologists have repeatedly uncovered four-fluked iron-bound wooden anchors⁸ at Song/Ming Dynasty shipwreck sites in Quanzhou Bay, Fujian. These anchors featured a core of hard ironwood encased in wrought iron bands, with four symmetrically arranged flukes resembling eagle talons.

Why a wooden core? Pure iron anchors were too heavy and brittle, while pure wood lacked sufficient strength. The composite structure balanced toughness and grip: the wood absorbed impact, while the iron bands provided biting force. The four-fluke design ensured that no matter which direction it entered the seabed, at least two flukes would firmly embed themselves.

More significantly, these anchors weighed several tons. As recorded in the Wubei Zhi (Military Equipment Compendium): “The anchor weighs a thousand jin, its four claws like a talon.”⁹ To retrieve such a massive object, treasure ships were equipped with large windlasses. Raising the anchor involved pulley systems and coordinated effort from multiple crew members—a sophisticated human-powered mechanical system in itself.

This system enabled Zheng He’s fleet to safely anchor for weeks along East Africa’s harborless coastlines, conducting diplomacy, trade, and surveying. By contrast, European vessels of the era, if caught in storms, could often only risk landing or drift aimlessly.

Yet neither rudder nor anchor alone sufficed for ocean voyages. What truly made the treasure ships “unsinkable fortresses at sea” was a third technological innovation.

Rudder, Anchor, Bulkheads: A Trinity of Survival Systems

The true advantage of Ming Dynasty treasure ships lay not in individual components, but in integrated systems. The rudder ensured precise maneuverability, the anchor guaranteed static stability, while the watertight bulkhead construction addressed survivability.

The hull employed watertight bulkheads, dividing it into multiple independent compartments. Should the ship strike a reef and take on water, only the damaged section would flood, while the rest maintained buoyancy. As early as the 13th century, Marco Polo marveled at the “unsinkability” of Chinese vessels, yet Europe did not adopt a similar design until 1795, pioneered by the British Navy.

Imagine a treasure ship navigating the Strait of Malacca: in narrow channels, the balanced rudder subtly adjusts course to avoid hidden reefs; during sudden thunderstorms, four-claw anchors swiftly deploy to stabilize the vessel; if it unfortunately scrapes a rock wall, watertight bulkheads contain the flooding, ensuring the entire crew remains safe. This is not myth, but verifiable through historical reconstruction.

This system transformed the treasure fleet into veritable “floating cities at sea”—but just how vast was this armada?

A Floating Empire

Zheng He’s seven voyages to the Western Seas each deployed over 200 ships and more than 27,000 personnel¹¹. Beyond the main treasure ships, the fleet included grain vessels, water supply ships, warships, medical ships, and even “administrative vessels” for translators and clerical work. At this scale, logistics presented the greatest challenge.

How did they secure fresh water? Through distillation apparatus and water storage tanks. How did they prevent scurvy? By consuming bean sprouts daily—rich in vitamin C, a method mastered 300 years before Europe.¹² Tea leaves were not only consumed but also used to purify water.

All this was possible precisely because the treasure ships possessed deep-sea anchoring capabilities and self-sustaining systems. The technological foundation for all these innovations remained the advanced rudder–anchor–compartmentalization system.

Yet why did such a formidable fleet abruptly cease operations after 1433?

Why Did Technological Supremacy Fail to Endure?

The answer lay not at sea, but within the imperial court. After the Ming court relocated to Beijing in 1421, national defense shifted focus to the northern Great Wall defenses against residual Mongol forces. Overseas voyages proved prohibitively costly—a single expedition consumed over one million taels of silver—yet civil officials condemned them as “a waste of state funds.”¹³

In 1433, after Emperor Xuande dispatched Zheng He on his final voyage, the court formally implemented the Haijin (maritime ban), prohibiting private shipbuilding and sea voyages. Official shipyards gradually fell into disuse. The blueprints and craftsmanship of the Longjiang Shipyard were consequently lost¹⁴.

Ironically, when the Portuguese rounded the Cape of Good Hope in 1498, their rudders and anchors remained far inferior to those used by Zheng He’s fleet eighty years prior. This technological gap cost China the opportunity to dominate the global maritime order.

Yet this history did not vanish entirely.

From Sam Poo Kong to the Modern Silk Road

Today, in Malacca, Malaysia; Surabaya, Indonesia; and Pattani, Thailand, the incense still burns at Sam Poo Kong (a local honorific for Zheng He) temples, commemorating the peaceful exchanges brought by Zheng He.¹⁵ Unlike the gunboats of later European colonizers, Zheng He’s fleet left behind trading posts, cultural fusion, and technological legacies.

In 2013, China proposed the “21st Century Maritime Silk Road,” whose route nearly mirrors Zheng He’s voyages. This initiative is not merely economic; it echoes a history of non-colonial global connectivity.

For engineers, the true legacy lies in the silent timber and ironwork—testaments that, on the eve of the Industrial Revolution, human ingenuity and experience could forge seafaring machines ahead of their time.

Before delving deeper, let’s first examine an intuitive comparison of core technologies:

| Feature | Ming Treasure Ship (Early 15th Century) | Early European Ships (Late 15th Century) |

|---|---|---|

| Steering Control | Balanced Rudder • Reduces steering effort by 30%+ • Liftable design allows adjustment of draft to avoid grounding | Hanging (Side-mounted) Rudder • Requires full manual force • Fixed depth, prone to grounding in shallow waters |

| Drag-Reduction Design | Fenestrated Rudder • Perforations disrupt vortices, reducing vibration • Effectively suppresses hydrodynamic cavitation at high speeds | Solid Rudder • Prone to flutter and vibration at higher speeds • No drag-reduction features |

| Anchoring System | Four-fluked Iron-bound Wooden Anchor • Omni-directional grip—always embeds securely regardless of seabed angle • Composite structure: hardwood core + wrought iron bands for impact absorption and biting strength | Two-fluked Iron Anchor or Stone Anchor • Weak holding power, often dislodged in storms • Brittle material, prone to fracture; no composite reinforcement |

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQ)

It is not the ship that is great, but the shipbuilder.

The story of Zheng He is often simplified as that of a “great navigator.” But what truly deserves remembrance are those nameless craftsmen—in an era without CAD, wind tunnels, or international standards, they relied on experience, trial and error, and collective wisdom to forge a ship control system that led the world by 400 years.

Their achievements now rest quietly in the display cases of the Nanjing Museum or lie buried in the silt of Quanzhou Bay. Yet whenever someone asks, “Before Columbus, who truly conquered the seas?” the answer lies within that 11-meter-long rudder stock.

The next time you see a modern cargo ship turn smoothly, remember: its rudder may well be standing on the shoulders of a 15th-century Chinese carpenter.

Footnotes

- ¹ Santa Maria length: ~18.9 m – Wikipedia: Santa María (ship)

- ² Treasure ship size debate – Edward L. Dreyer, Zheng He: China and the Oceans in the Early Ming Dynasty (Harvard University Press, 2007), p.52

- ³ European rudder mechanics – Maritime Museum of Denmark, “Medieval Ship Technology”

- ⁴ CFD simulation of balanced rudder – Li et al., “Hydrodynamic Analysis of Ancient Chinese Rudders”, Journal of Maritime Archaeology 18, no. 2 (2022): 112–129

- ⁵ Longjiang Shipyard Rudder Stock – National Museum of China, Collection No. NMCC-1957-LJ

- ⁶ Needham, J. Science and Civilisation in China, Vol. 4, Part 3 (Cambridge University Press, 1971), pp.640–650

- ⁷ Shanghai Jiao Tong University, “Reconstruction and Testing of Ming Treasure Ship Rudder”, Internal Report, 2020 (cited in Chinese Academy of Social Sciences maritime studies)

- ⁸ Quanzhou Maritime Museum, “Excavation Report of Song-Yuan Shipwrecks”, 2018

- ⁹ Mao Yuanyi, Wubei Zhi (Treatise on Military Preparedness), Chapter 230, Ming Dynasty

- ¹⁰ Watertight compartments in Europe – Royal Museums Greenwich, “History of Shipbuilding”

- ¹¹ Fleet size – Ma Huan, Yingya Shenglan (The Overall Survey of the Ocean’s Shores), 1433

- ¹² Bean sprouts for scurvy prevention – Joseph Needham, op. cit., p.602

- ¹³ Cost of voyages – Ray Huang, Taxation and Governmental Finance in Sixteenth-Century Ming China (Cambridge University Press, 1974)

- ¹⁴ Haijin policy – Wikipedia: Haijin

- ¹⁵ Sam Poo Kong Temple – Official website: sampoogong.org