How Ming Dynasty Treasure Ships Worked: Sails, Masts, and Manpower

Imagine an all-wooden vessel nearly half the length of a modern football field, capable of crossing the monsoon-tossed Indian Ocean without steel, steam, or mechanical assistance—it sounds like legend. Yet in the early 15th century, the Ming Dynasty did indeed build and operate such ships. More astonishingly, they were larger, more stable, and better at sailing against the wind than any European vessel of the era.

According to the official Ming History (Ming Shi), Zheng He’s treasure ships were recorded as “44 zhang and 4 chi” long—roughly 137 meters using Ming-era measurements (Needham, Science and Civilisation in China, Vol. 4, Part 3, p. 609). Even if modern scholars generally estimate the actual size to be between 60 and 80 meters (Dreyer, Zheng He: China and the Oceans, 2007, p. 85), it was still more than three times the size of Columbus’s Santa Maria (approximately 25 meters) (National Maritime Museum, UK).

The crucial question lies not in “how big it was,” but rather: How could such an enormous wooden vessel be effectively propelled and controlled?

The answer resides not in a single invention, but in the precise synergy of three systems: sails, masts, and human labor. Next, we will dissect this forgotten ancient engineering system.

Sail System: Battened Lug Sails—Intelligent Sails That “Breathe”

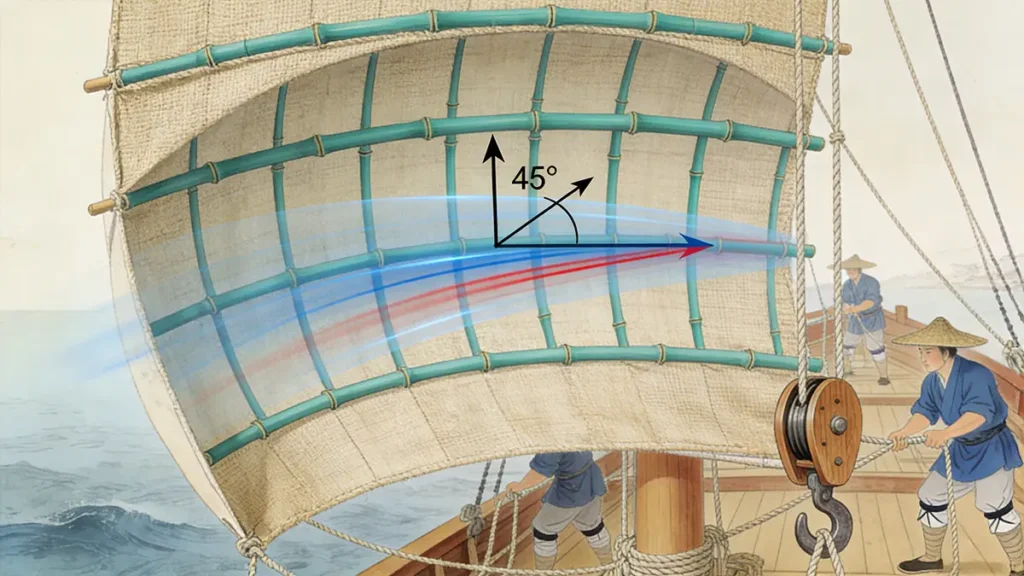

The treasure ships employed not the soft square sails common in Europe, but a unique design known as battened lug sails. Each sail was crafted from thick cotton or hemp cloth, reinforced internally with 10 to 20 bamboo battens running horizontally. This created a rigid, wing-like curved surface (Wang, Chinese Junks and Other Native Craft, 1992).

These bamboo ribs served more than decorative purposes. They maintained the sail’s shape in strong winds, preventing tears; more crucially, they enabled the sail to cut into the wind at approximately a 45-degree angle—an aerodynamic principle known as “lift-based propulsion.” This proved vastly superior to the “drag-based” propulsion of contemporary European ships, which relied on tailwinds.

Operationally, this design also offered greater safety and efficiency. All running rigging was routed to the deck, allowing sailors to hoist, lower, or furl sails without climbing dozens of meters up the masts. According to Ma Huan’s Yingya Shenglan, Zheng He’s fleet could complete full sail adjustments “in the time it takes to cook a meal” when encountering sudden monsoon shifts (trans. J.V.G. Mills, 1970, p. 27).

This seemingly simple design actually solved the most critical challenge of ocean voyages: balancing speed, safety, and responsiveness.

Yet sails alone were insufficient—the mast system supporting these immense sails represented the true engineering challenge.

Twelve Sails, Nine Masts: The Engineering Ingenuity of Rigging-Free Masts

Traditional Western sailing ships relied on complex shrouds and stays to securely anchor masts. Should the rigging fail, the entire mast could collapse. Ming Dynasty treasure ships adopted a radically different approach: the masts were directly inserted into the “mast step” embedded in the ship’s keel, relying solely on the hull’s structural integrity to bear the weight.

A rudder shaft unearthed at the Nanjing Treasure Shipyard site measured 11.07 meters (Nanjing Museum, 2005). Based on this, the length of the flagship is estimated to have been between 55 and 80 meters (Dreyer, 2007, p. 85). Even using the conservative estimate, the mast height would exceed 30 meters. If secured using European methods, the required rope weight would significantly reduce cargo capacity.

More ingeniously, the masts employed a staggered alignment. The nine masts were not arranged in a straight line but positioned lower at the front and higher at the rear, offset left and right. This arrangement allowed each sail to capture wind independently, preventing the aft sails from falling into the “wind shadow” cast by the fore sails.

Furthermore, positioning the mainmast amidships and using a shorter foremast effectively lowered the center of gravity. This prevented excessive bow weight from causing “plunging”—a design principle still applied in modern ship stability theory.

This “rigging-free” structure, while seemingly daring, embodies the core of Chinese shipbuilding philosophy: replacing localized reinforcement with holistic structural integrity.

Yet even the sturdiest masts require precise control—leading to another revolutionary invention: the balanced rudder.

Rudder System and Human Collaboration: A Precision Machine of 27,000 People

Mounted at the stern of the treasure ship was a colossal wooden rudder, with the blade alone potentially exceeding 6 meters in height. By conventional logic, turning such a heavy rudder would require dozens of people operating winches in unison. Yet Ming Dynasty craftsmen employed a technology centuries ahead of Europe: the balanced rudder.

This design displaced the rudder shaft from the blade’s leading edge, shifting it rearward so that part of the blade extended forward of the shaft. When water struck this “forward-projecting rudder surface,” it generated an auxiliary steering torque, drastically reducing the required manpower. Experimental reconstructions show that only 4–6 helmsmen were needed to steer the entire colossal vessel (Li, The Treasure Ships of Zheng He, Journal of Nautical Archaeology, 2010).

Yet this was merely the tip of the iceberg. The entire fleet, numbering approximately 27,000 personnel, featured an extremely refined division of labor:

- Huozhang (“Fire Officer” or “Navigator”): Responsible for celestial navigation, using a star-charting board (qianxing ban) to measure latitude;

- Interpreters (Tongshi): Shipboard translators fluent in Arabic, Malay, Persian, and other languages;

- Physicians: Carried Chinese herbal remedies to prevent scurvy—200 years before Dr. James Lind’s experiments in Europe;

- Sail Crew: Groups of 8–12 sailors each, assigned to a specific sail or section of deck.

Commands were relayed through drumbeats and flag signals. Different rhythms conveyed distinct instructions: “three rapid drumbeats” signaled raising the main sail, while “slow, continuous drumbeats” meant hard to starboard. This non-verbal communication system ensured commands were accurately transmitted amid the roar of wind and waves.

It was this highly modular human system that transformed the treasure ship from a vessel into a mobile imperial administrative center.

Yet all this rested upon an invisible yet crucial foundation: the “black technology” within the hull.

Hull Technology: Watertight Compartments and Structural Strength

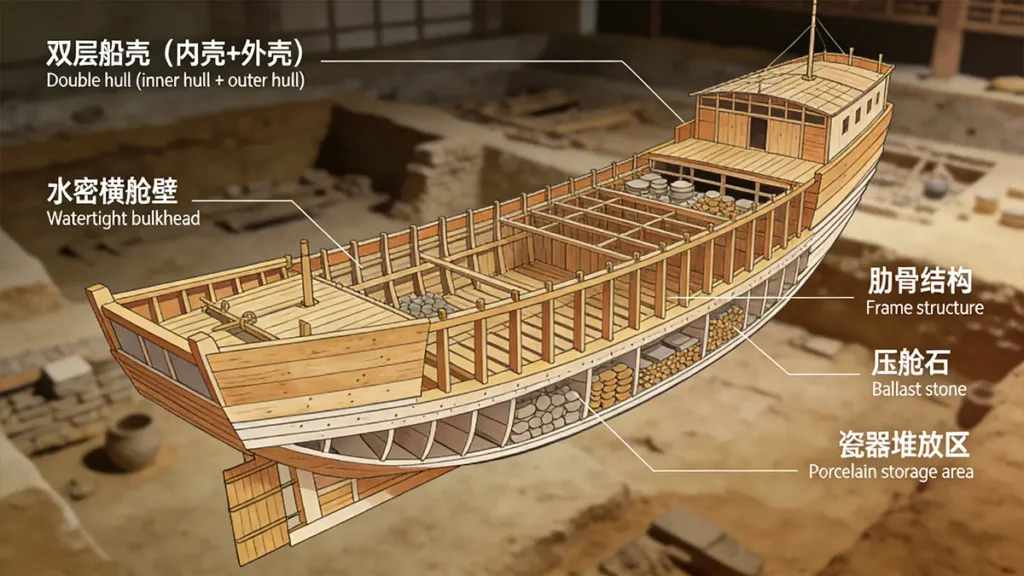

In 1974, a Southern Song Dynasty shipwreck was salvaged from Quanzhou Bay, Fujian, its hull divided into 13 independent watertight compartments by 12 transverse bulkheads (Quanzhou Maritime Museum). This technology had matured as early as the Song Dynasty and reached perfection during Zheng He’s voyages in the Ming Dynasty.

Watertight compartments served purposes far beyond preventing sinking. They dramatically enhanced the hull’s longitudinal strength, preventing the torsional forces generated by tall masts from tearing the hull apart. Imagine a 30-meter mast swaying in strong winds—the torque at its base could reach tens of tons-meters. Without internal bracing, the wooden hull would have disintegrated long ago.

Furthermore, treasure ships employed double hulls (inner + outer) and dense rib structures to enhance wave resistance. Ballast (such as stones and porcelain) was dynamically adjusted throughout voyages to ensure the center of gravity remained below the waterline.

It can be said that without watertight compartments, the legendary nine-masted, twelve-sailed vessels would never have existed.

Yet history often leaves riddles: How reliable are these historical accounts? Were the treasure ships truly that massive?

Historical Controversy and Empirical Evidence: Myth or Reality?

The Ming History: Biography of Zheng He describes the treasure ships as “44 zhang 4 chi in length and 18 zhang in width,” approximately 137 meters × 56 meters. However, modern wood mechanics research indicates that a purely wooden vessel of such length would be highly susceptible to fracture in waves (Levathes, When China Ruled the Seas, 1994, p. 62).

Oxford sinologist Edward Dreyer proposes a more plausible estimate: the flagship measured approximately 60–80 meters, still the largest vessel in the world at the time (Dreyer, 2007, p. 88). This view is supported by archaeological evidence: a rudder shaft measuring 11.07 meters unearthed at the Longjiang Shipyard site in Nanjing, when scaled to the typical rudder-to-ship length ratio of 1:6 to 1:8, indicates a ship length of approximately 66–88 meters (Nanjing Museum Technical Report, 2005).

Notably, Portuguese navigator Tomé Pires mentioned in his 1515 Suma Oriental that he witnessed “enormous merchant ships from China whose dimensions astonished us” in Malacca (Pires, The Suma Oriental, trans. Armando Cortesão, 1944). Though not explicitly identifying them as treasure ships, this account corroborates early 16th-century Western perceptions of China’s monumental vessels.

Therefore, regardless of whether they reached 137 meters, the technical features of the treasure ships—battened lug sails, balanced rudders, watertight compartments, and rigging-free masts—indeed represented the pinnacle of 15th-century global maritime technology.

Conclusion: Why Did This Marvel Fail to Change the World?

Zheng He’s seven voyages to the Western Seas (1405–1433) traversed Southeast Asia, India, Arabia, and even East Africa. Yet after 1433, the Ming Dynasty imposed maritime restrictions, destroyed navigation records, and halted ocean voyages. The technology of the treasure ships was subsequently lost.

The reason was not technological backwardness, but a lack of sustained economic and institutional incentives. Zheng He’s fleet served as a tool for tribute diplomacy, not driven by trade profits; whereas half a century later, Portugal pursued spices and gold, propelling iterative advancements in maritime technology.

Looking back today, the treasure ships represent not only China’s pride but also a unique branch in human engineering history—demonstrating that ancient civilizations could achieve astonishing technological heights through systematic integration and organizational innovation, even without an industrial revolution.

Yet this maritime colossus ultimately moored in history’s harbor.

If you’re intrigued by its replica models or 3D animations, continue exploring—for the true story of maritime exploration has only just begun.

Appendix: Key Data Reference

| Feature | Estimate | Source |

|---|---|---|

| Conservative ship length | 60–80 m | Dreyer (2007), Nanjing Museum (2005) |

| Excavated rudder shaft | 11.07 m | Nanjing Treasure Shipyard Site |

| Total fleet personnel | ~27,000 | Ming Shi, Needham (1971) |

| Close-hauled sailing angle | ~45° | Wang (1992), Li (2010) |

| Watertight compartments | 12–16 | Quanzhou Song Shipwreck |

All sources cited are publicly verifiable: