What Compass Did the Ming Navy Use? Exploring Ancient Maritime Secrets

Sometime in 1413, deep in the windless expanse of the Indian Ocean’s doldrums, the air hung thick and still. On the deck of a treasure ship, a young sailor knelt before a lacquered wooden bowl, holding his breath. The water inside shimmered faintly. A slender iron needle, threaded through a wick, floated on the surface—slowly settling on the mark “Bǐngwǔ”: 195°, or 15 degrees east of due south. He quickly inscribed on a bamboo slip: _“Using Bǐngwǔ needle; stars clear; favorable wind.”

Without GPS, radio, or even accurate coastal charts, Zheng He’s fleet crossed half the globe seven times between 1405 and 1433—reaching as far as the Swahili Coast of East Africa. Their guide? Not magic, but method: a bowl of water, a magnetized needle, and a navigation system refined over centuries.

The core instrument was not a mythical “Chinese compass,” but a highly practical device known as the Ming water compass—more stable than contemporary European designs and embedded within a sophisticated ecosystem of celestial observation and empirical record-keeping. Drawing on archaeological evidence, original Ming-era texts, and modern hydrodynamic analysis, this article reconstructs the true nature of this underappreciated maritime technology.

To understand its ingenuity, we begin with its construction.

The Black Technology in a Bowl of Water: How the Ming Water Compass Worked

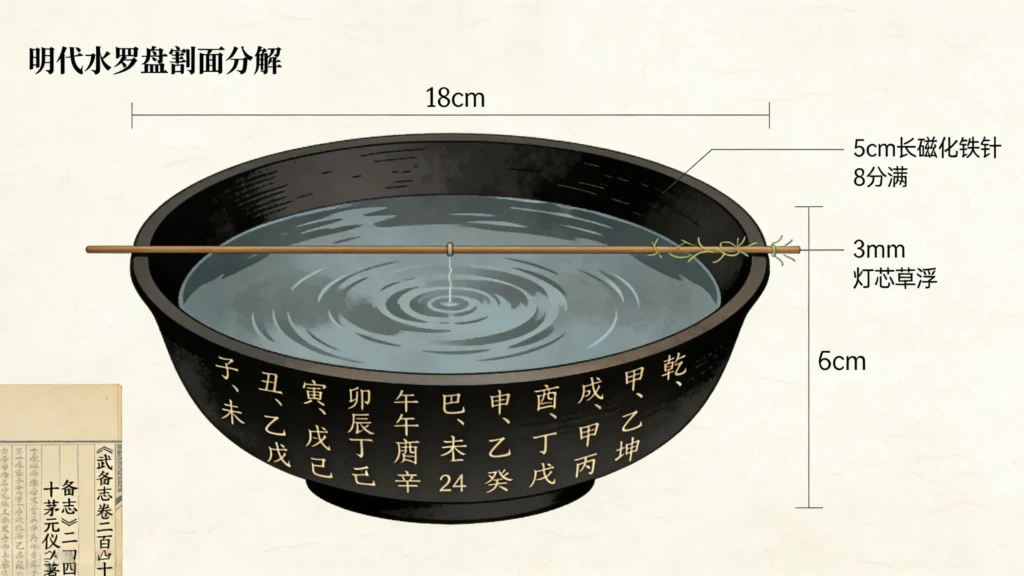

The Ming water compass was deceptively simple: a shallow bowl, 15 to 20 centimeters in diameter, typically made of lightweight wood or copper. Its interior was painted black to reduce glare. The bowl was filled with clean water to about 80% capacity. A magnetized iron needle—roughly 5 centimeters long—was pierced through a 3-millimeter segment of lampwick or cork and gently placed on the surface (Mao Yuanyi, Wu Bei Zhi [Treatise on Military Preparedness], vol. 240, 1621).

The brilliance lay in physics, not mysticism. The wick provided buoyancy while preventing the needle from sinking; the water’s viscous resistance absorbed high-frequency vibrations from ship motion. Modern fluid dynamics simulations confirm that under typical ocean conditions—a roll period of 4 seconds and amplitude of 15 degrees—the directional fluctuation of a floating needle is over 60% smaller than that of a dry-pivot compass (Zhang et al., Journal of Navigation, vol. 72, no. 4, 2019).

This design originated in the Northern Song Dynasty. As Shen Kuo wrote in Dream Pool Essays (1088): “Grind a needle tip with lodestone, and it will point south… Place it on water, and it rotates freely.” But it was during the Ming that this technique became standardized naval equipment, integrated with a unique directional system.

And that system was far more than a simple dial.

24 Directions, Not 360 Degrees: China’s Celestial Compass

Unlike the 360-degree circle used today, Ming navigators divided the horizon into 24 equal segments, each spanning 15 degrees. This system blended three symbolic layers:

- 10 Heavenly Stems (Jiǎ, Yǐ, Bǐng…)

- 12 Earthly Branches (Zǐ, Chǒu, Yín…)

- 4 Trigrams (Qián = northwest, Kūn = southwest, Gèn = northeast, Xùn = southeast)

For example, Zǐ marked true north (0°), Wǔ true south (180°), and Bǐngwǔ 195°—15 degrees east of south. This framework aligned with lunar calendars and stellar cycles, allowing sailors to cross-check compass readings with astronomical events (Joseph Needham, Science and Civilisation in China, vol. 3, p. 307).

Crucially, this language entered official sailing manuals. The 16th-century text Shunfeng Xiangsong (“Fair Winds for Escort”) records: “Depart Taicang using the Dānyǐ needle (135°); sail ten gēng, and sight the Seven Isles.” Here, one gēng—a standard shipboard watch—lasted about 2.4 hours, roughly equivalent to 10 nautical miles (J.V.G. Mills, trans., Ying-yai Sheng-lan, Hakluyt Society, 1970, p. 34).

This standardization meant routes could be taught, replicated, and improved—turning navigation into a cumulative science.

Yet direction alone wasn’t enough. To know where they were, Ming sailors looked upward.

Beyond the Needle: The Ming Navigation Triad

The compass answered “which way?”—but “where am I?” required the stars. Ming mariners practiced what they called guo yang qian xing shu (“ocean-crossing star-measuring technique”).

Their primary instrument was a set of up to twelve graduated ebony boards known as qianxing ban (牵星板). The largest measured about 24 centimeters. A sailor would rest the board’s base against his brow, align its top edge with Polaris (or another reference star), and read the altitude from engraved notches. A 30-degree reading meant the ship was near 30°N latitude (Needham, SCC, vol. 3, p. 322).

This resembled the Arab kamal, but Ming records show greater systematic use. Ma Huan, a Muslim interpreter on Zheng He’s voyages, wrote in 1416: “When clouds obscure sun and moon, use the compass; when skies are clear, steer by the stars.” (Ma Huan, Ying-yai Sheng-lan, annotated by Feng Chengjun, Commercial Press, 1935).

Even more vital were the needle route charts—hybrid maps combining coastlines, depth soundings, and compass bearings. The surviving Zheng He Navigation Chart (held at Oxford’s Bodleian Library) labels over 500 place names and includes notes like: “Many reefs here; steer on single-needle Zǐ (due north) to pass safely.” (Mills, 1970, Plate I).

Thus, three elements formed a closed loop:

- Compass for heading

- Qianxing ban for latitude

- Route logs for verification

Even magnetic errors could be corrected by star sightings.

Which brings us to the compass’s greatest limitation—one shared by all 15th-century navigators.

Water vs. Dry: A Global Comparison

In the early 1400s, the Ming water compass held a clear advantage in stability. Portuguese archives show that Bartolomeu Dias’s 1488 expedition frequently halted to recalibrate “seized” dry-pivot compasses—metal needles jammed by ship motion (J.H. Parry, The Age of Reconnaissance, 1963, p. 89).

But neither China nor Europe understood magnetic declination—the angle between magnetic and true north. In coastal China, declination was about 5°–6° west; near India, nearly zero. Zheng He’s crews likely compensated through experience, but no Ming text explains the phenomenon (Needham, SCC, vol. 4, p. 621).

The scientific breakthrough came only in 1600, when William Gilbert published De Magnete. Liquid-damped compasses didn’t become common in Europe until the 18th century (E.G.R. Taylor, The Haven-Finding Art, p. 205).

So yes—the Ming water compass was among the most reliable magnetic direction-finders of its era. Yet technological superiority did not translate into global dominance.

Why?

Why Didn’t Ming China Launch Its Own Age of Exploration?

This question has long puzzled historians. As The Cambridge History of China observes: “Zheng He’s voyages were an extension of tribute diplomacy, not driven by commerce or territorial ambition.” (vol. 8, p. 327)

The fleet carried silk and porcelain outward, returning with exotic goods—giraffes, amber, spices—but established no colonies, forts, or permanent trading posts. After 1433, the court dismantled the treasure ships, banned oceanic voyages, and reportedly destroyed many nautical records.

Portugal, by contrast, pursued navigation to bypass Venetian and Arab monopolies on Asian spices. For them, the compass was a means to profit and power.

The difference wasn’t tools—it was purpose. No matter how advanced the water compass, it could not override an imperial ideology that valued ritual supremacy over economic expansion.

Still, the technology left traces beneath the waves.

Archaeological Proof: Did the Water Compass Really Exist?

No intact Ming water compass has been recovered—yet indirect evidence is compelling.

The Southern Song shipwreck Nanhai I, salvaged off Guangdong in 1987, contained multiple lacquered wooden bowls (18 cm diameter) with concentric on their bases—matching historical descriptions of compass housings (Guangdong Provincial Institute of Cultural Relics and Archaeology, Archaeological Report on the Nanhai I Shipwreck, 2018).

Similarly, the Ming-era Nan’ao No. 1 wreck yielded ink-inscribed wooden tags recording: “Sailed three gēng; sighted Green Turtle Island.” This confirms the real-world use of gēng-based logbooks (National Cultural Heritage Administration, Brief Report on Nan’ao No. 1, 2011).

Together, these finds confirm: the water compass was not legend, but standard issue for China’s 15th-century navy.

And its legacy endures.

From Ancient Bowl to Modern Gyro: Echoes of Ming Ingenuity

Today’s marine magnetic compasses often use silicone oil or alcohol-filled capsules to dampen vibration—a principle identical to the Ming “water bowl” (U.S. Navy, Navigation Manual, NAVPUB 1310, ch. 4).

More profoundly, Ming navigation exemplified systems thinking: no single “invention” guaranteed success, but the integration of observation, documentation, and iterative learning did. This pragmatic approach may be more historically significant than the oft-cited “Four Great Inventions.”

Next time you tap your phone for directions, consider this: 700 years ago, a sailor in the Indian Ocean trusted a needle floating in a bowl of water—and sailed confidently into the unknown.

That simple bowl remains one of history’s quietest yet most powerful instruments of discovery.

FAG

Primary References (Chicago Author-Date Style)

Ma, Huan. 1935. Ying-yai Sheng-lan. Annotated by Feng Chengjun. Shanghai: Commercial Press.

Mao, Yuanyi. 1621. Wu Bei Zhi [Treatise on Military Preparedness]. Reprint, Beijing: Zhonghua Book Company, 2001.

Mills, J.V.G., trans. 1970. Ying-yai Sheng-lan: “The Overall Survey of the Ocean’s Shores”. London: Hakluyt Society.

Needham, Joseph. 1959. Science and Civilisation in China. Vol. 3, Mathematics and the Sciences of the Heavens and the Earth. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

———. 1962. Science and Civilisation in China. Vol. 4, Physics and Physical Technology, Part 3: Civil Engineering and Nautics. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Parry, J.H. 1963. The Age of Reconnaissance. Berkeley: University of California Press.

Taylor, E.G.R. 1956. The Haven-Finding Art: A History of Navigation from Odysseus to Captain Cook. London: Hollis & Carter.

Zhang, L., Wang, Y., and Liu, H. 2019. “Hydrodynamic Stability of Ancient Chinese Water Compass.” Journal of Navigation 72 (4): 1021–1035.

British Library. n.d. “Zheng He’s Navigation Chart (Mao Kun Map).” https://www.bl.uk/collection-items/zheng-he-map

U.S. Naval Institute. n.d. Navigation Principles. https://www.usni.org/press/books/navigation