What is a Watertight Bulkhead? The Ancient Chinese Technology That Saved Ships for Centuries

Imagine a 13th-century Chinese ocean-going sailing vessel crashing into reefs during a storm. Seawater surges into the hull—yet the ship does not sink. It slowly makes its way back to port, carrying its crew and cargo.

During the same period, a European merchant ship facing a similar disaster would almost certainly meet with total loss of life.

The difference between life and death lay in a ship safety technology originating in ancient China: the watertight bulkhead.

What is a Watertight Bulkhead and how did it save ships?

A watertight bulkhead is a transverse structural partition within a ship’s hull that creates independent, leak-proof compartments. Originating as a 2nd-century Chinese invention, this technology saves ships by confining hull damage to a single section, preventing total flooding and maintaining buoyancy—a revolutionary safety feature that predated Western adoption by centuries.

This is not merely a “partition within the ship,” but a complete survival system. Its core purpose is singular: to preserve the vessel’s buoyancy through physical isolation, even if the hull suffers localized damage. So how exactly does this technology function? And what archaeological evidence substantiates its existence?

Archaeological Evidence Chain: From Eastern Han Dynasty Pottery Boats to Quanzhou Song Dynasty Shipwrecks

The earliest known physical evidence of watertight compartments comes from an Eastern Han Dynasty ceramic ship model unearthed in Guangzhou in 1955 (circa 200 AD). This model already featured distinct transverse partition structures, indicating that Chinese craftsmen of the time had developed a preliminary concept of “compartmentalization to prevent sinking” (Joseph Needham, Science and Civilisation in China, Vol. 4, Part 3, p. 648).

True maturity in this technology emerged during the Song Dynasty. In 1974, the wreck of a 13th-century ocean-going Fujian junk (historically known as the “Quanzhou Ancient Ship”) was discovered in Quanzhou Bay, Fujian. Archaeological excavation confirmed the vessel possessed twelve fully enclosed watertight compartments. Each compartment featured thick transverse wooden bulkheads extending from the keel to the main deck, forming independent sealed units. Residual grayish-black filler at the seams was identified through chemical analysis as “chunam”—a traditional waterproof sealing compound made from quicklime, tung oil, and hemp fibers (Quanzhou Museum of Maritime History, 2023).

The ship’s design indicates that watertight compartments had become standard equipment on Chinese ocean-going vessels by the Song and Yuan dynasties (10th–14th centuries) at the latest, rather than a mere experimental feature.

What Is a Watertight Bulkhead in a Ship?

The effectiveness of watertight compartments relies on the synergy of three key technical elements:

First is the structural jointing method. Chinese shipbuilders employed tongue-and-groove joints: shaping the edges of planks into interlocking convex and concave forms that fit together like puzzle pieces. This connection not only ensures tightness but also maintains structural integrity under wave impact, preventing gaps from widening due to vibration.

Second is the waterproof sealing material. All seams are filled with “chunam”—a lime-based sealant. Modern laboratory tests reveal that upon contact with seawater, chunam undergoes a slow chemical reaction, gradually hardening into a composite material denser than wood, effectively blocking water molecule penetration. This self-healing seal ensures bulkheads maintain watertight integrity during prolonged voyages.

Finally, buoyancy control principles apply. According to fundamental fluid dynamics laws, a vessel remains afloat as long as buoyancy from dry compartments exceeds its total weight. Watertight bulkheads physically isolate sections, preventing localized damage from triggering cascading flooding and thus preserving overall stability.

Additionally, these transverse bulkheads enhance the hull’s longitudinal rigidity, reducing rolling motion during navigation. This improves ocean-going seaworthiness and crew comfort.

What Is the Purpose of Watertight Bulkheads?

Its purpose extends far beyond merely “preventing sinking.” The core function of watertight compartments is to enable damage control: containing disasters locally to preserve the whole.

This concept had reached a high level of sophistication by the Song Dynasty. The 12-compartment design of the Quanzhou ship was engineered so that in the event of reef strikes, collisions, or planking fractures, sacrificing a single compartment would allow the remainder to remain seaworthy for the return voyage. This “fault tolerance” gave Chinese merchant ships a distinct survival advantage during long-distance voyages across the Indian Ocean and South China Sea.

Marco Polo documented this in his late 13th-century Travels:

“Their ships are built with thirteen separate compartments… Even if one or two compartments are damaged and take on water, the remaining compartments remain intact, and the ship does not sink.” (The Travels of Marco Polo, Book III, Chapter I.)

This account confirms that watertight compartments were already a visible and verifiable mature technology at that time.

Why Did the West Delay Its Adoption? Differences in Design Philosophy

Despite the proven effectiveness of watertight compartments, European shipbuilders did not begin systematic trials of similar designs until the late 18th century. The Royal Navy conducted its first official test of watertight compartments in 1795 (N.A.M. Rodger, The Command of the Ocean, p. 321).

This delay stemmed not from technical limitations but from fundamentally different shipbuilding priorities. From the Middle Ages through the early modern period, European vessel design primarily served warfare and trade efficiency: pursuing higher speeds, larger gun deck spaces, and more flexible cargo hold layouts. Safety, particularly survivability, was not a core concern.

In contrast, Chinese ocean-going junks, long engaged in peaceful trade, prioritized vessel durability and crew survival. Consequently, redundant safety designs were incorporated into standard construction practices much earlier.

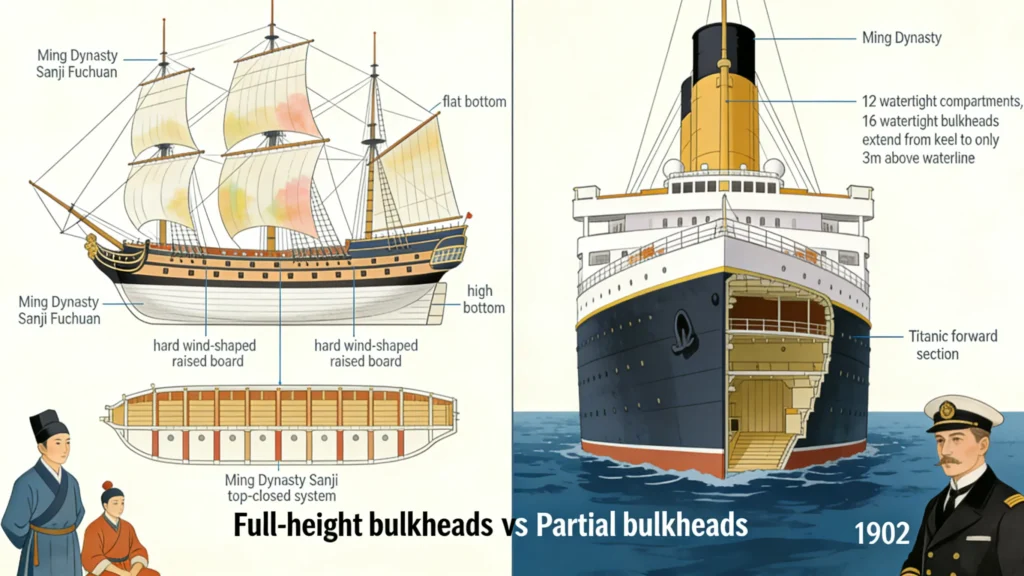

The Titanic’s Counterexample: Incomplete Watertight Design

The sinking of the Titanic in 1912 exposed the fatal flaw of its “pseudo-watertight compartments.” Although the ship featured 16 watertight compartments, their bulkheads rose only about 3 meters (10 feet) above the waterline and did not extend to the upper deck. When the iceberg ripped open multiple forward compartments, seawater rapidly flooded these sections. It then overflowed from the tops into adjacent compartments, ultimately causing the entire ship to lose buoyancy and sink (1912 British Wreck Commissioner’s Report, Section 22).

In contrast, the Song Dynasty ship from Quanzhou featured bulkheads extending from the keel to the deck, forming a fully enclosed structure that achieved true “watertight” integrity. Chinese craftsmen clearly understood that if water could overflow from the top of compartments, compartmentalization would be rendered meaningless. This critical design detail determined the difference between life and death.

While the watertight bulkhead was the cornerstone of safety, it was just one component of a much larger system of advanced maritime logistics and ship types that defined the Ming Dynasty’s naval supremacy.

Modern Legacy: From Intangible Cultural Heritage to International Maritime Standards

Today, the fundamental principle of watertight compartments has become the cornerstone of global vessel safety. The International Convention for the Safety of Life at Sea (SOLAS) mandates that all commercial ships—including cargo vessels, passenger ships, tankers, and even aircraft carriers—must incorporate watertight subdivision to minimize the risk of sinking.

Meanwhile, this traditional craftsmanship continues to thrive. In 2010, UNESCO officially inscribed “Watertight-Bulkhead Technology of Chinese Junks” onto the Representative List of the Intangible Cultural Heritage of Humanity. In Fujian’s Quanzhou and Ningde regions, artisans like Zhang Guohui continue to handcraft seaworthy traditional junks, preserving core techniques such as tongue-and-groove joints, chunam-sealed caulking, and fully enclosed bulkheads (UNESCO Intangible Heritage Archive).

This practice not only honors history but perpetuates an efficient, sustainable engineering wisdom.

Eternal Value

Watertight compartments originated as a ship safety technology in China during the 2nd century AD. By installing transverse sealed bulkheads within the hull, the vessel is divided into multiple independent compartments. This design limits water ingress to localized areas in the event of damage, thereby preserving overall buoyancy. Archaeological discoveries, historical records, and modern practice collectively demonstrate that this technology predates similar Western designs by over 1,500 years and continues to influence shipbuilding to this day.

Its true value lies not in “who invented it first,” but in how a simple, reliable, and low-cost structural solution addresses complex maritime safety challenges—an engineering philosophy that transcends time and space, remaining effective to this day.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQ)

Authoritative Reference Materials

- UNESCO. (2010). Watertight-Bulkhead Technology of Chinese Junks. https://ich.unesco.org/en/RL/00398

- Quanzhou Maritime Museum. (2023). Exhibition on Song Dynasty Shipwreck.

- Needham, J. (1971). Science and Civilisation in China, Vol. 4, Part 3. Cambridge University Press.

- British Wreck Commissioner. (1912). Report on the Loss of the Titanic.

- Rodger, N.A.M. (2004). The Command of the Ocean. Yale University Press.