Why Did China Stop Its Treasure Fleet? 5 Real Reasons Behind the End of Zheng He’s Voyages

China didn’t stop Zheng He’s voyages because it fell behind technologically. It stopped them by choice—driven by fiscal strain, northern threats, bureaucratic power consolidation, resurgent Sinocentrism, and a deliberate policy of maritime retreat: what we call “The Great Closure.” This decision marked an early signal of the “Great Divergence”—while Europe turned toward the oceans, China chose the land.

The “Supremacy” That Vanished Overnight

Imagine this: in 1405, a fleet of 27,000 men sailed from Nanjing. Its flagship—the “Treasure Ship”—stretched 120 meters, carried nine masts, twelve sails, and could hold over a thousand crew.

Eighty-seven years later, in 1492, Christopher Columbus set out with just 90 men on the 18-meter Santa Maria, venturing into the unknown Atlantic.

Zheng He’s fleet dwarfed anything Europe could muster—not just in size, but in technology and logistical sophistication. This wasn’t parity; it was supremacy.

Yet by the year Columbus was born (1451), the Ming Dynasty had already dismantled its treasure ships, burned its nautical charts, and banned oceanic voyages.

This raises a haunting question: Why would a civilization with absolute maritime dominance voluntarily abandon the seas?

The answer lies not in tools or timber—but in institutions.

Zheng He: The Outsider Who Commanded an Empire’s Fleet

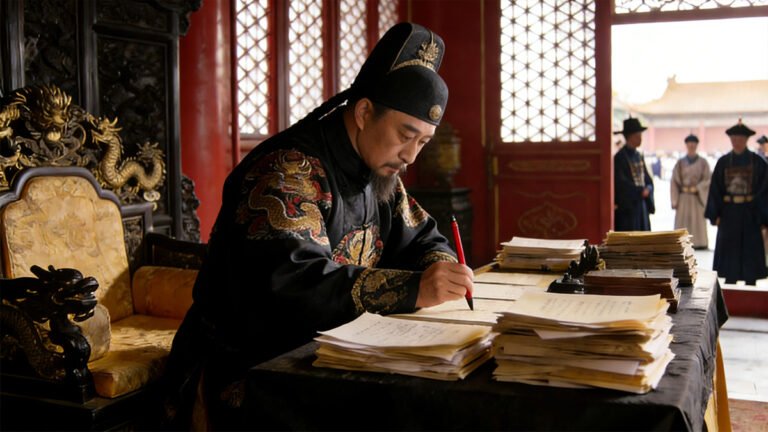

To understand this turning point, consider Zheng He himself. Born Ma He in Yunnan, he was a Muslim captured as a child during war, castrated, and brought into the imperial palace as a servant. He was both a eunuch and a Muslim—an outsider serving an alien faith at the heart of a Confucian empire.

The Yongle Emperor elevated him precisely to circumvent the entrenched Confucian bureaucracy. Zheng He’s seven voyages were, at their core, an audacious attempt by imperial authority to break free from institutional constraints.

But when Yongle died in 1424, that experiment collapsed.

The Triumph of the Bureaucracy: Institutional Inertia in Action

Western readers may recognize the term “Deep State”—referring to unelected institutions that shape policy regardless of leadership changes. In Ming China, this role belonged to the Confucian civil service, recruited through rigorous exams and deeply invested in preserving agrarian stability.

These were not passive scholars. They controlled appointments, budgets, and ideology. To them, Zheng He’s expeditions represented three threats:

- Political: Eunuchs gaining influence through naval patronage

- Fiscal: “Prestige projects” draining the treasury

- Ideological: Foreign contact undermining the moral order of a self-sufficient realm

After 1433, they moved swiftly—not out of ignorance, but as a rational defense of their vision of order. Their victory wasn’t conservatism; it was institutional self-preservation.

And once set in motion, this inertia proved unstoppable—even by emperors.

The Great Closure: A Systematic Retreat from the World

The Ming maritime ban—often called haijin—was far more than a simple prohibition. It was a coordinated policy of withdrawal we term “The Great Closure.” It operated on three levels:

| Type of Barrier | Policy Action |

|---|---|

| Physical | Ban on building ships with more than two masts |

| Knowledge | Destruction of Zheng He’s archives (1477) |

| Ideological | Promotion of Sinocentrism—the belief that China, as the “Middle Kingdom,” needed nothing from the outside world |

This mirrors later historical episodes: America’s Monroe Doctrine, Cold War autarky, or today’s “technological decoupling.” All cloak strategic retreat in the language of security.

The result? Within a century, China forgot it ever ruled the waves. By the Jiajing era (1522–1566), the largest warships measured just 30 meters—less than a quarter the length of Zheng He’s flagships.

Finance, Incentives, and the Missing Property Rights

Zheng He’s voyages were not economic ventures. They were state-led rent-seeking: resources flowed to court favorites, not productive enterprise.

Each expedition cost roughly 6 million taels of silver—nearly one-third of the Ming’s annual revenue—with virtually no return. This triggered a severe crowding-out effect: funds for flood control, border defense, and famine relief were slashed.

Most critically, the state refused to recognize private property rights in overseas trade. Any merchant who sailed risked confiscation or execution.

Meanwhile, Europe was doing the opposite. Through chartered companies—like Portugal’s Casa da Índia or later the Dutch East India Company—governments granted legal monopolies, profit shares, and territorial rights. Risk was shared; rewards were real.

That institutional difference explains why Europe’s oceanic push became self-sustaining—and China’s did not.

Five Institutional Reasons the Voyages Ended

| Reason | Explanation |

|---|---|

| 1. Fiscal Unsustainability | Each voyage consumed ~30% of annual revenue with zero ROI |

| 2. Northern Security Threat | Mongol raids forced reallocation of resources to land defense |

| 3. Bureaucratic Counterattack | Civil officials suppressed eunuch power and “disruptive” projects |

| 4. Resurgent Sinocentrism | Ideology framed external engagement as unnecessary or dangerous |

| 5. The Great Closure | Deliberate erasure of maritime knowledge, technology, and memory |

Ming China vs. Early Modern Europe: Two Paths, One Divergence

| Dimension | Ming China | Europe (Portugal/Spain) |

|---|---|---|

| Power Structure | Bureaucracy vs. Emperor | Crown allied with merchant class |

| Economic Logic | State monopoly; no private rights | Chartered companies + profit sharing |

| Risk Model | 100% state-funded | Public-private risk sharing |

| Ideology | Sinocentrism (“We have all”) | Commercial expansionism (“Go and profit”) |

| Long-Term Outcome | Maritime capacity collapsed | Global trade networks emerged |

As Daron Acemoglu and James Robinson argue in Why Nations Fail, extractive institutions suppress innovation; inclusive ones unleash it. The Ming chose extraction—and paid the price in lost futures.

Today’s Echo: Is History Repeating?

Zheng He’s story isn’t just about the past. It resonates powerfully today.

We now live in an age of “tech decoupling”:

- Nations restrict AI, chips, and space collaboration in the name of “national security”

- Administrative mandates replace market incentives

- “Self-reliance” slogans mask policies that stifle cross-border innovation

Under the banner of “independent innovation,” are we enacting a 21st-century Great Closure?

The Ming lesson is stark: No technological lead—however vast—is safe without inclusive institutions, secure property rights, and an open ecosystem. Without them, even supremacy becomes ephemeral.

True strategic foresight isn’t measured by the spectacle of launch—but by whether breakthroughs become embedded in institutions that outlive their creators.

Deep Dive: Sources & Frameworks

- Ming Shi (History of Ming): “Sixty-two treasure ships built, each 44 zhang long [≈120m].”

- Yan Congjian, Shuyu Zhouzi Lu: “Minister Liu Daxia destroyed the archives, fearing future generations might imitate them.”

- Acemoglu & Robinson, Why Nations Fail (2012): Extractive institutions block creative destruction.

- Kenneth Pomeranz, The Great Divergence (2000): Europe and Asia diverged due to institutional and ecological path dependencies.

- Huang Renyu, Taxation and Finance in 16th-Century Ming China: Rigid fiscal system incapable of absorbing commercial variables.

References:

- Veritable Records of the Ming Dynasty

- History of the Ming Dynasty (Ming Shi)

- Yan Congjian, Records of Foreign Lands (Shuyu Zhouzi Lu)

- Acemoglu, D., & Robinson, J. (2012). Why Nations Fail. Crown.

- Pomeranz, K. (2000). The Great Divergence. Princeton University Press.

- Huang, R. (1974). Taxation and Governmental Finance in Sixteenth-Century Ming China. Cambridge.

- Xi, L. (2005). History of Chinese Shipbuilding. Hubei Education Press.