From Bukhara to the Great Ocean: The Central Asian Roots of Admiral Zheng He

When Christopher Columbus sailed across the Atlantic in 1492 with three small ships, Zheng He had already completed Zheng He’s seven epic voyages across the Indian Ocean—87 years earlier—commanding a fleet of over 250 vessels, including 62 colossal “treasure ships.” His flagship stretched 130 meters long—equivalent to one and a half football fields. It wasn’t merely a ship; it was a floating city.

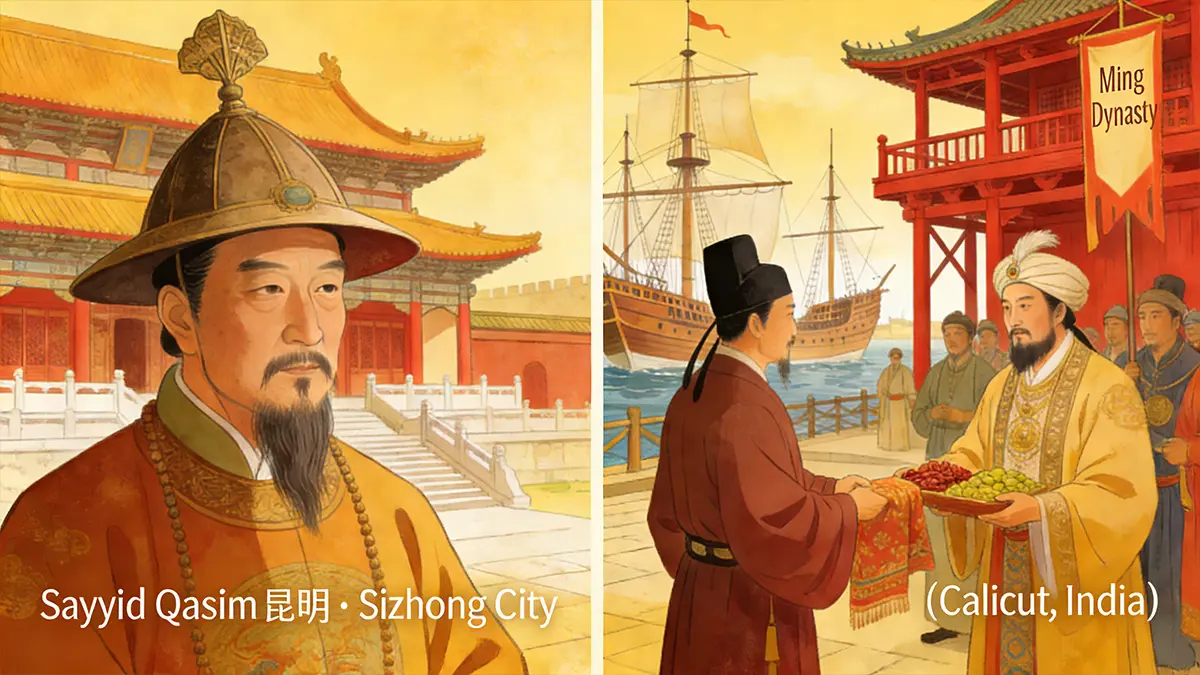

What made him so extraordinary? Zheng He was not only the supreme naval commander of China’s Ming Dynasty but also a descendant of Central Asian Muslims whose family story began in the glittering Silk Road city of Bukhara (in modern-day Uzbekistan).

Before delving into this trans-Eurasian saga, consider this key comparison:

The Great Age of Exploration – A Comparison

| Feature | Zheng He’s Fleet (1405–1433) | Columbus’s Fleet (1492) |

|---|---|---|

| Number of Ships | 250+ (including 62 massive “Treasure Ships”) | 3 (Santa Maria, Pinta, Niña) |

| Flagship Length | ~130 m (426 ft) — 1.5 football fields | ~18 m (60 ft) — about a city bus |

| Crew Size | ~27,800 (soldiers, doctors, translators, astronomers) | ~90 sailors |

| Navigation Technology | Watertight compartments, magnetic compass, star charts | Dead reckoning, astrolabe |

| Primary Mission | Diplomacy, tribute trade, conflict mediation | Find a new route to India (ultimately launched colonization) |

This table reveals a long-overlooked truth: Zheng He represented a maritime order that was non-colonial, non-missionary, and rooted in peaceful exchange.

1. Was Zheng He’s Ancestor Really a Descendant of the Prophet?

The earliest prominent ancestor in Zheng He’s lineage was Sayyid Ajjal Shams al-Din Omar, a high-ranking official during the Yuan Dynasty (1271–1368). In 1274, Kublai Khan appointed him as the first Governor-General of Yunnan Province—a role combining civil administration and military command.

Where did he come from?

- Geographic origin: Bukhara, a major center of Islamic scholarship on the Silk Road (now in Uzbekistan), once part of the Persian cultural sphere.

- Ethnic identity: Yuan records describe him as a “Huihui” (a historical term for Muslims from Central Asia). Modern scholars refer to his community as Central Asian Muslims or Hui ancestors.

- Claim of prophetic descent: He used the title Sayyid—indicating descent from the Prophet Muhammad. However, American sinologist Morris Rossabi notes this was likely a political strategy to gain legitimacy under Mongol rule, not a genealogically verified fact (Khubilai Khan, 2009, p.186).

Despite the debate over his lineage, Sayyid Ajjal’s governance in Yunnan was transformative: he built Confucian temples, restored mosques, and dredged Dianchi Lake. Today, Kunming’s Zhong’ai Pavilion stands in his honor (Kunming Municipal Culture & Tourism Bureau).

His legacy laid the foundation for a century of family prominence—until the fall of the Yuan Dynasty brought everything to an abrupt end.

2. From Ma He to Zheng He: A Name Forged in War

Zheng He was born Ma He—“Ma” being a common surname among Chinese Muslims at the time, derived from “Muhammad.”

In 1894, a stone epitaph titled “Epitaph of the Late Lord Ma” was unearthed in Kunyang, Yunnan (modern Jinning District, Kunming). It reads:

“The gentleman, styled Hajji, bore the surname Ma. His family resided in Kunyang Prefecture… He passed away in the Renxu year of the Hongwu era (1382).”

“Hajji” signifies that his father had completed the pilgrimage to Mecca. This stele, now housed in the Kunming Museum (exhibition link), is the most crucial physical evidence of Zheng He’s origins.

In 1382, Ming forces conquered Yunnan, crushing the last Yuan loyalists. Zheng He’s father, a member of the former Yuan elite (Semu ren—a Yuan classification for non-Han, non-Mongol Western peoples), died in battle. The ten-year-old Ma He was captured.

According to the Veritable Records of the Ming Taizu, boys from defeated enemy families were often castrated and taken into imperial service. But crucially: Ming eunuchs were not mere palace servants. They served as the emperor’s most trusted agents—diplomats, intelligence officers, and military commanders. Their role resembled that of a modern National Security Advisor.

Ma He’s fortunes changed during the Jingnan Campaign (1399–1402), a civil war in which he fought loyally for Prince Zhu Di. When Zhu Di ascended the throne as the Yongle Emperor in 1404, he rewarded Ma He with a new surname: Zheng—taken from Zheng Village Dam (Zhengcunba), where the emperor had once garrisoned (now in Beijing’s Chaoyang District).

Thus, “Ma He” vanished—and “Zheng He” was born.

That a captured boy of Central Asian descent could rise to command the world’s most powerful navy remains one of history’s most astonishing transformations.

3. Muslim by Birth, Buddhist by Title: The Complexity of Faith

Zheng He was undoubtedly a Muslim:

- He funded the construction of mosques in Nanjing and Xi’an.

- In 1413, he sent his deputy Ma Huan on a pilgrimage to Mecca. Ma Huan later recorded his journey in Yingya Shenglan (The Overall Survey of the Ocean’s Shores), now held at the National Library of China (nlc.cn).

Yet he also embraced Buddhism:

- He called himself “the eunuch Sanbao” (Sanbao = “Three Jewels”: Buddha, Dharma, Sangha).

- He printed Buddhist scriptures and erected steles invoking Mazu, the sea goddess, for safe voyages.

As scholar Jonathan N. Lipman explains, Ming-era Hui elites often practiced what he calls “external Confucianism, internal Islam, with Buddhist and Daoist adaptations” (Familiar Strangers, 1997, p.45). At court, they used Buddhist titles to integrate; in private, they maintained Islamic rituals.

This was not contradiction—it was strategic pluralism in a multi-religious empire.

4. From Yunnan to the Western Oceans: A Legacy of Governance

Sayyid Ajjal governed Yunnan through conciliation, infrastructure, and religious tolerance. Centuries later, Zheng He embodied the same philosophy on a global scale.

During his seven voyages (1405–1433), he never seized territory. Instead, he:

- Established trade posts

- Mediated local conflicts

- Shared Chinese technology (like papermaking and calendar systems)

Historian Li Qingxin argues this “non-conquest diplomacy” directly echoed his ancestor’s principle of “governing according to local customs.”

Family memory may fade—but the governance gene endures.

5. Can DNA Confirm His Central Asian Roots?

Evidence is indirect but compelling.

In 2016, Yunnan University tested Y-chromosomes of Ma-family clans claiming descent from Zheng He. Some carried haplogroup L1a-M76—common in Iran, Pakistan, and northwest India (Journal of Anthropology, 2017, No. 3). Data is publicly accessible via the YFull database.

However, caution is essential: Zheng He had no children. These “descendants” are collateral relatives. The strongest evidence remains:

- Textual: Ming Shi (History of Ming), tomb inscriptions

- Archaeological: The “Epitaph of the Late Lord Ma”

- Genetic: Consistent Central Asian markers in associated lineages

6. Did Zheng He Know He Came from Bukhara?

Almost certainly not—or if he did, he never said so.

In 1431, he erected a stele in Changle, Fujian, declaring:

“Zheng He, devout follower of Buddhism, native of Kunyang, Yunnan.”

He never mentioned Sayyid Ajjal, never referenced “Hui” identity, and never named Bukhara.

By the 15th century, his family had lived in Yunnan for nearly 150 years—fully Sinicized. The “Silk Road ancestry” we reconstruct today is a modern scholarly inference, not an identity he claimed.

Do not project our genealogical obsessions onto a man who saw himself simply as a loyal servant of the Ming Empire.

Authoritative Sources:

- Original “Epitaph of the Late Lord Ma”: Kunming Museum

- Morris Rossabi, Khubilai Khan: His Life and Times, University of Washington Press, 2009

- Jonathan N. Lipman, Familiar Strangers: A History of Muslims in Northwest China, University of Washington Press, 1997

- Li Qingxin, Research on the Overseas Trade System of the Ming Dynasty, Social Sciences Academic Press, 2006

- Y-chromosome data: YFull YTree – Haplogroup L1a

- Ma Huan, Yingya Shenglan (The Overall Survey of the Ocean’s Shores): National Library of China