Who Was Wang Jinghong? The Co-Commander Who Brought Zheng He’s Fleet Home

Wang Jinghong (c. 1369–1434) was not merely Zheng He’s subordinate, but the second-in-command of the Ming Dynasty’s maritime expeditions. After Zheng He’s death in India in 1433, it was Wang who single-handedly led over 200 treasure ships, nearly 30,000 officers and soldiers, and envoys from dozens of nations back to China safely, completing the most complex long-distance naval retreat of the 15th century. He was also the only core member entrusted with overseas missions by Ming emperors after Zheng He’s passing.

Yet today, almost no one knows his name. This article explains why he remains so significant yet forgotten by history.

1. He Was Not a “Supporting Role,” But an Officially Appointed Joint Commander

Wang Jinghong was a Han Chinese from Zhangping, Fujian. This point warrants emphasis—for his homeland of Fujian was one of the crucial starting points of the ancient Maritime Silk Road. Since the Tang and Song dynasties, cities like Quanzhou, Fuzhou, and Zhangzhou had served as centers for China’s foreign trade and shipbuilding industries. Generations of local residents were intimately familiar with monsoons, shipping routes, and transoceanic voyages. Wang Jinghong’s upbringing was inherently steeped in this profound maritime culture.

He entered the palace as a eunuch, not of Hui or Muslim descent (a point often confused, as Zheng He was of Yunnan Hui origin). During the Yongle and Xuande reigns, he repeatedly sailed as the “Chief Eunuch Envoy,” ranking second only to Zheng He.

Crucial evidence comes from the 1431 Stele of Foreign Trade Achievements erected at Tianfei Temple in Liujiagang, Taicang, Jiangsu. The inscription explicitly states:

“Eunuchs Zheng He and Wang Jinghong were dispatched to command tens of thousands of soldiers and sailors aboard forty-eight ocean-going vessels…”

This inscription was not a retrospective account but an official record engraved before the fleet’s seventh voyage, confirming Wang Jinghong’s status as a co-commander alongside Zheng He, not merely an attendant (as interpreted by the Nanjing Museum).

It is crucial to note: High-ranking eunuchs in the Ming Dynasty were far from mere palace servants. In Europe, “eunuch” often referred to powerless court attendants; in China, however, emperors entrusted eunuchs with military and political authority precisely because they were deemed “without descendants and without selfish motives.” As a “Grand Eunuch of the Palace Bureau,” Wang Jinghong served as the emperor’s direct proxy, empowered to command armies, conduct diplomacy, and allocate resources—this constituted the core logic of the Ming dynasty’s system of “eunuchs controlling generals.”

2. 1433: He Assumed Command of the Most Perilous Maritime Crisis in History

The Seventh Maritime Expedition (1431–1433), originally conceived as a diplomatic mission of peace, took a sudden turn in 1433: Zheng He, aged 62, passed away in Calicut (present-day Kozhikode, India).

At this juncture, the fleet was deep in the Indian Ocean, comprising:

- Over 200 vessels (including more than 60 large Treasure Ships)

- Nearly 30,000 officers, sailors, physicians, and interpreters

- Diplomatic missions from dozens of nations across Arabia, East Africa, and Southeast Asia

Mismanagement could have sparked mutiny, pirate attacks, or diplomatic catastrophe.

Wang Jinghong swiftly assumed command. According to the Veritable Records of the Ming Emperor Yingzong:

“Wang Jinghong and others escorted all foreign envoys back to their homelands before returning to the capital to report.” (Volume 11, 1434)

This signified not only a safe return but the fulfillment of all diplomatic missions—without losing a single vessel or provoking conflict.

His success stemmed from a sophisticated cross-cultural management system: the fleet carried “interpreters” fluent in Arabic, Malay, and even Swahili; an “official supply station” was established in Malacca to store provisions, transmit documents, and host envoys. Wang Jinghong’s true prowess lay in his coordination and mastery of this multilingual, multi-religious, multi-ethnic system.

3. He May Have Led the “Eighth Voyage”

Traditional accounts state that Zheng He undertook “seven voyages to the Western Seas,” but historical records indicate that Wang Jinghong continued executing overseas missions after 1433.

The Veritable Records of the Ming Xuanzong Emperor, Volume 112, records that in the ninth year of the Xuande reign (1434), envoys from Sumatra, Ceylon, and other nations arrived in China, all of whom were received by Wang Jinghong. Based on this, Professor Li Jinming of Xiamen University speculates that Wang may have led a portion of the fleet southward again in 1434 to escort the envoys back to their countries—this could be regarded as an unofficial “Eighth Voyage” (Zheng He’s Voyages to the Western Seas and Southeast Asia, 2005).

He was the only core member of Zheng He’s original team who continued to oversee diplomatic affairs after Zheng He’s death, demonstrating the imperial court’s profound trust in his capabilities.

4. What Kind of Fleet Did He Command?

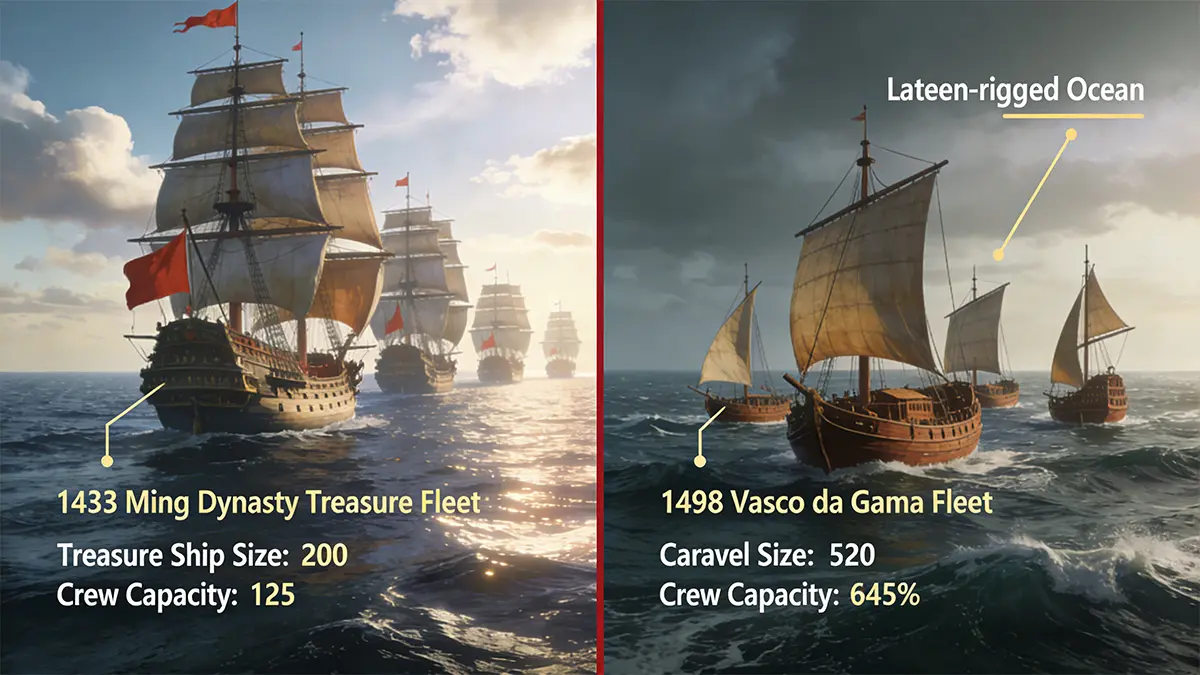

To grasp Wang Jinghong’s achievements, one must understand the scale he commanded:

- Flagship Treasure Ships: 120–130 meters (approx. 400 feet) long, over 50 meters wide, with a displacement potentially exceeding 10,000 tons—longer than a standard soccer field;

- Technical Advantages: Watertight compartments (sink-proof), balanced rudders (agile steering), multiple masts with square sails (efficient monsoon utilization);

- Crew: 27,000–28,000 personnel, including physicians, astronomers, translators, and soldiers (Encyclopædia Britannica).

Comparison: In 1498, 65 years later, Vasco da Gama’s fleet rounding the Cape of Good Hope comprised only four small vessels with 170 crew members, the largest ship measuring just 25 meters (Mariners’ Museum).

More significantly: This fleet never established colonies, plundered resources, or forced conversions. Its mission was to “preach virtue and win over distant peoples”—maintaining regional peace through displays of national strength, accepting tributes, and mediating disputes. On its return voyage, it brought back mostly giraffes (mistaken for “qilin”), spices, and friendly envoys, not gold or slaves.

Wang Jinghong commanded not merely a fleet, but a transoceanic mobile city operating within a maritime order where trade and diplomacy replaced military force.

5. Why Did History Erase Him?

Three structural reasons:

- Policy Reversal: In 1436, the Ming Dynasty officially “disbanded the Treasure Ships,” dismantled shipyards, and banned private maritime voyages. The collective downfall of naval heroes followed.

- Minimal Historical Documentation: The Ming History’s Biographies of Eunuchs mentions him in just 37 characters: “Wang Jinghong, native of Zhangping, repeatedly accompanied Zheng He on missions to the Western Seas.”

- Modern Narratives Favor “Lone Heroes”: Since the 20th century, Zheng He has been portrayed as “China’s Columbus,” naturally marginalizing his collaborators.

This is akin to the Apollo 11 moon landing: the world remembers only Armstrong stepping onto the moon, while forgetting Michael Collins, the astronaut who remained alone in the command module ensuring their safe return. Wang Jinghong was the “Collins” of the Ming fleet.

At a deeper level, the disappearance of Treasure Ship technology wasn’t because “the Chinese weren’t good at navigation,” but because the entire system was highly dependent on state monopoly. Once the imperial court ceased investment (such as with the 1436 maritime ban), the Longjiang shipyard closed, craftsmen dispersed, and the technology rapidly vanished. In contrast, contemporary Europe saw shipbuilding driven by merchants, city-states, and royal courts, fostering greater resilience—a difference rooted in institutional frameworks, not capability.

Recent scholarship, however, has begun correcting this bias. German sinologist Angela Schottenhammer observes:

“Wang Jinghong was not a shadow, but the bridge between ambition and legacy.”

6. His Legacy Endures Overseas

In Semarang, Central Java, Indonesia, the renowned Sam Poo Kong Temple venerates the “Eunuch Sanbao.” A crucial detail often overlooked is that ‘Sanbao’ was not Zheng He’s name, but rather the honorific title for the “Chief Eunuch Envoy” during the Ming Dynasty—akin to the dignified designation “Imperial Commissioner.”

Therefore, as a “Chief Eunuch Envoy” of equal rank, Wang Jinghong was also known as “Sanbao” at the time. This signifies that the temple commemorates the spiritual symbol of the entire embassy, not just Zheng He alone. Wang Jinghong’s legacy and reputation have long been woven into the incense offerings of this temple.

In China, Fujian’s Zhangping hosts the Wang Jinghong Memorial Hall (official website), showcasing his life and maritime contributions.

True leadership is bringing people home.

Today, the “Maritime Silk Road” is often mentioned, but its true legacy lies not in the routes themselves, but in a maritime tradition that replaced military expansion with peaceful engagement—Wang Jinghong was the last practitioner of this tradition.

Zheng He’s greatness lay in pioneering; Wang Jinghong’s greatness lay in concluding. As the empire turned inward and the maritime endeavors abruptly ceased, it was he who ensured this largest peaceful fleet in human history returned to its home port intact, orderly, and with dignity.

History should not only remember those who ignite the flame, but also those who guard the embers through storms until the very last moment.

References

- Verified Edition of Veritable Records of the Ming Dynasty, Zhonghua Book Company

- Nanjing Museum: Transcription of the Stele Inscription on Foreign Trade at Liujiagang

- Li Jinming, Zheng He’s Voyages to the Western Seas and Southeast Asia, Ocean Press, 2005

- Angela Schottenhammer, The Chinese Navy in the Age of Zheng He, Brill, 2021

- Zhangping Municipal Government Official Website

- Encyclopædia Britannica, Mariners’ Museum