Food and Fresh Water on Zheng He’s Treasure Ships: Feeding 27,000 Men at Sea

In 1415, aboard a Ming dynasty vessel in the central Indian Ocean, a sailor named Afu lifted a damp burlap sack to reveal sprouting mung beans beneath, their tips just turning white. Imagine this: in a ship’s hold thick with salty sea air, the stench of rotting timber, sweat, and acrid charcoal smoke, that small patch of tender green wasn’t just vitamin C—it was the only visible sign of life these men had left.

This isn’t romantic fiction. The fleet’s interpreter, Ma Huan, recorded it plainly in his Yingya Shenglan (The Overall Survey of the Ocean’s Shores): “The sailors soaked mung beans in water to sprout them, eating them daily to ward off the ‘sea disease.’” That “sea disease” was almost certainly scurvy. Europeans wouldn’t confirm the curative power of vitamin C until 1747, when British naval surgeon James Lind used lemons to treat his crew. Honestly, every time I read Ma Huan’s line, I can’t help but think: while Ming sailors were munching fresh sprouts, their European counterparts were still gnawing on moldy hardtack.

But what’s even more staggering is the scale. On Zheng He’s seventh voyage, the crew alone numbered over 27,000—more than the population of London at the time. They drank more than 50,000 liters of water a day and ate nearly 30 tons of rice. These aren’t estimates; they’re drawn straight from the Ming Shi—the official History of Ming. So how did they pull it off without refrigeration, water purifiers, or multivitamins?

The answer wasn’t in the size of their ships—but in the intelligence of their entire logistical system.

The fleet wasn’t one ship—it was a floating supply chain

When people hear “Zheng He,” they often picture a single, mythical 120-meter “treasure ship.” Historians still debate whether that number is exaggerated—some say it’s plausible, others call it propaganda. But here’s what no one disputes: no single vessel could possibly feed 27,000 people.

Zheng He’s fleet was, in fact, a highly specialized maritime ecosystem. Beyond a handful of treasure ships used for diplomacy and display, the majority were grain carriers (liangchuan), water tenders, horse transports, and warships. Archives unearthed at Nanjing’s Longjiang Shipyard (on the Qinhuai River) show that a typical expedition deployed over 60 large vessels, backed by hundreds of support craft. Grain ships hauled rice and salt. Water ships carried freshwater. And yes—they even had dedicated kitchen ships.

As maritime historian Edward L. Dreyer puts it in Zheng He: China and the Oceans in the Early Ming Dynasty: “Zheng He’s success depended not on ship size, but on organizational mastery.” And he’s right. When Columbus sailed in 1492, his three ships carried fewer than 90 men total. Zheng He routinely commanded fleets of tens of thousands capable of sailing nonstop for six months or more. It wasn’t even close.

Which brings us to the real lifeline: water.

Freshwater: Life stored in barrels—more precious than gold

At sea, water is survival. Zheng He’s fleet needed over 50,000 liters a day—enough to fill more than 20 standard bathtubs. How did they store it? Keep it clean? Replenish it?

First, the containers were carefully engineered. They used large fir-wood barrels, their interiors coated with quicklime or beeswax to kill microbes and block woody flavors from seeping into the water. For drinking water, they often used sealed ceramic jars. I’ve seen replicas at the Nanjing Museum—waist-high barrels lined up in the lower hold like a wine cellar.

Second, the ships themselves helped. Ming treasure ships featured watertight bulkheads—a design that isolated each compartment so that if one flooded or spoiled, the rest stayed safe. This technology predated European adoption by at least 600 years and is now recognized by UNESCO as a cornerstone of the Maritime Silk Road.

But the real genius was in resupply. Zheng He didn’t drift—he followed a “freshwater corridor.” His route linked trusted ports: Malacca, Calicut (in modern-day India), Hormuz in the Persian Gulf. At each stop, porcelain and silk were traded for local water. Ma Huan noted that in Sumatra, “the king sent men to deliver water to the ships, exchanging it for porcelain”—a clear example of supply diplomacy, not conquest.

Still, water alone doesn’t keep an army alive. What about food?

It wasn’t just salted fish: fermentation, spices, and psychological sustenance

Forget Hollywood. Ming sailors didn’t survive on salted fish and rice alone.

Rice was the staple—but adjusted by region: southerners got rice, northerners millet or wheat. Meat existed, but sparingly. Pork was heavily salted, then smoked with Sichuan pepper, cinnamon, and star anise—not just for flavor, but as a preservation method. Reading Tiangong Kaiwu (The Exploitation of the Works of Nature), it’s clear Ming engineers knew spices doubled as antimicrobials.

Even more vital were fermented foods: douchi (fermented black beans), soy sauce, and preserved tofu. High in protein, shelf-stable, and deeply savory, they turned bland rations into something bearable. Out on the open ocean, a spoonful of pungent fermented tofu might have felt like a shot of pure vitality—far more than any preserved ration could offer.

But what struck me most was their grasp of psychological nourishment. Those bean sprouts weren’t just nutrition—they were hope. Picture a sailor staring at grimy decks, breathing in sweat and brine, then glancing down at a few green shoots in his bowl. In that moment, it must have felt like an astronaut seeing Earth from orbit.

And speaking of sprouts—that may be the fleet’s quietest triumph.

Sprouts: A vitamin C factory that needed no soil, no sun—just three days

Scurvy haunted European voyages. When Vasco da Gama returned from his first trip around Africa in 1499, two-thirds of his crew were dead—most from bleeding gums, loose teeth, and skin hemorrhages: classic scurvy. Yet across Zheng He’s seven expeditions, there are virtually no records of such outbreaks.

Why? Because they grew their own cure onboard.

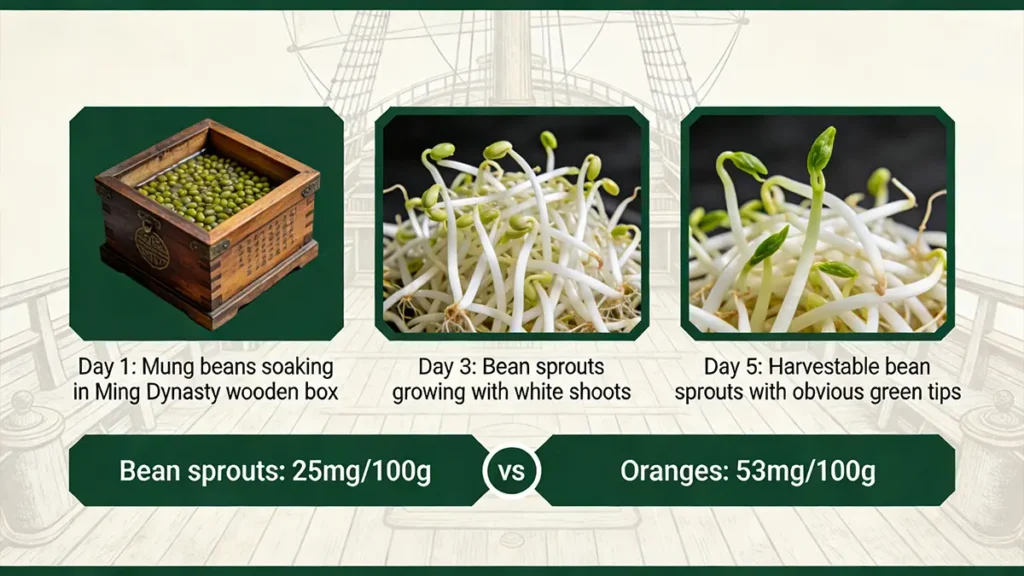

The method was astonishingly simple: soak mung beans for 24 hours, spread them in shallow wooden trays, cover with damp cloth, and store in a cool corner. The ship’s ambient heat and humidity did the rest. Sprouts appeared by day three; by day five, vitamin C peaked. According to USDA data, 100 grams of raw mung bean sprouts contain 20–30 mg of vitamin C—nearly as much as an orange.

Best of all, it cost nothing extra: no freshwater irrigation, no sunlight, barely any space. Ma Huan’s note about daily sprout consumption suggests this wasn’t occasional—it was routine. Every ship likely had someone tending rotating batches like a tiny floating farm.

Meanwhile, European sailors were still debating in the 1700s whether scurvy was divine punishment. Was this gap just about technology? I’d say it reflected something deeper: a fundamentally different understanding of how to sustain human life at sea.

Of course, even the best food system needs cooks.

The kitchen ship: a floating galley built for thousands

Zheng He’s fleet included purpose-built provision ships. Their lower decks were weighted with stone ballast for stability. Mid-decks held brick stoves with metal wind shields and chimneys venting straight to the open air—so cooking didn’t choke the whole vessel in smoke. Upper decks stored dry goods near water access points.

Meals followed rhythm, not luxury: light congee at dawn for easy digestion; hearty rice with pickles and bean-sprout soup at dusk for energy. Charcoal was the main fuel, and open flames were strictly controlled—fire zones clearly marked.

I once stood before a replica of Columbus’s Santa María at the National Maritime Museum in Greenwich. Its “galley” was a single iron stove wedged into a cargo corner. Zheng He’s kitchen ship? It looked like a central commissary. No wonder some Western scholars joke: “If Columbus had seen the Ming supply convoy, he’d have thought he was dreaming.”

Tragically, none of this survived.

Why did such a brilliant system vanish?

In 1433, the Xuande Emperor issued an edict halting all overseas voyages. Treasure ship construction stopped. Craftsmen scattered. The Longjiang Shipyard fell silent. The Ming Shilu (Veritable Records of the Ming) dismisses it with a line: “The treasure ships rotted away.” Behind those words lay the collapse of an entire knowledge network.

Worse, this logistical genius was never codified in official histories. Only fragments remain—in private journals like Ma Huan’s and Fei Xin’s. Centuries later, the West remembered Zheng He for his ships’ size—but forgot his true achievement: keeping 27,000 men alive, healthy, and fed across oceans.

Today, as we plan vegetable gardens for Mars colonies or closed-loop water systems for deep-sea habitats, maybe we should look back. Six hundred years ago, humans already ran a near-self-sustaining civilization on the waves of the Indian Ocean.

Its core ingredients? A barrel of clean water. A sack of mung beans. And a group of people who understood that survival isn’t about grandeur—it’s about respecting the smallest details of life.