The Giant Treasure Ships of the Ming Dynasty: A Complete Guide to Zheng He’s Fleet

Article Insight:At the height of the Ming Dynasty, Admiral Zheng He led a floating city of 208 ships and 27,000 men—a navy so vast it made Columbus’s three-ship voyage look like a fishing trip. Yet within decades, China burned its own fleet, erased its maps, and turned inward. This guide reveals the lost tech, the peaceful empire, and the great reversal that changed world history.

- Who Was Zheng He? The Slave Boy Who Commanded the World’s Largest Fleet

- How Big Were Zheng He’s Treasure Ships? Separating Myth from Archaeology

- How Did 27,000 Sailors Stay Organized? The Navy That Rivalled a City

- What Made Ming Ships Unsinkable? China’s Secret Naval Tech

- How Did They Navigate Without GPS? Star Charts and Magnetic Compasses

- How Did They Avoid Scurvy? The Bean Sprout Solution

- Why Did China Burn Its Own Fleet? The Great Maritime Reversal

- Where Are the Lost Treasure Ships? Hunting for Ming-Era Wrecks

- FAQ (Frequently Asked Questions)

- What Can the West Learn from Zheng He’s Peaceful Empire?

Who Was Zheng He? The Slave Boy Who Commanded the World’s Largest Fleet

In the summer of 1405, at Liujiagang in Taicang, Jiangsu, 208 colossal ships formed a majestic line along the river—masts like a forest, sails blocking the sun. On the deck of the flagship stood Admiral Zheng He, a former Hui prisoner of war from Yunnan, now the Yongle Emperor’s most trusted naval commander.

In Western imagination, “eunuch” often evokes intrigue or weakness. But Zheng He was no court schemer—he was a true admiral, leading a fleet equivalent to a floating city on missions of diplomacy, trade, and soft power projection across the Indian Ocean.

Who was the greatest Chinese commander?

China has produced countless land generals—but on the global maritime stage, Zheng He stands alone. Napoleon never sailed; Nelson commanded fleets of a few hundred. Zheng He, by contrast, led seven expeditions with up to 27,800 crew, visited over 30 countries, and never conquered a single inch of land.

His patron, Emperor Yongle (r. 1402–1424)—builder of the Forbidden City and founder of Beijing as capital—wasn’t searching for a missing rival emperor. He sought to establish a “Pax Ming”: a China-centered order of peace, maintained through a tribute and trade network that echoed Rome’s Pax Romana. Foreign rulers acknowledged the Ming emperor’s symbolic supremacy—not through force, but through ritual exchange.

How Big Were Zheng He’s Treasure Ships? Separating Myth from Archaeology

According to The Official Records of the Ming Dynasty (Ming Shi), the Treasure Ships (“Baochuan”) measured “44 zhang in length and 18 zhang in width.” One Ming-era zhang ≈ 3.1 meters, yielding dimensions of ~140 meters long and 57 meters wide.

Skeptics argue wooden ships couldn’t reach such sizes. Europe’s largest pre-industrial vessel, Sweden’s Vasa (1628), was just 69 meters—and sank on its maiden voyage.

But physical evidence exists: in 1957, archaeologists unearthed an 11.07-meter-long rudder post at Nanjing’s Longjiang Shipyard—the largest wooden ship component ever found. Naval engineers estimate this belonged to a vessel 138–158 meters long (Xi Longfei, History of Chinese Shipbuilding).

Most scholars now accept a “compromise theory”: only 1–2 ceremonial flagships exceeded 120 meters; the rest of the fleet used practical 50–70 meter vessels.

What is the biggest ship ever built?

Zheng He’s Treasure Ships were the largest wooden sailing ships in human history—a record held for nearly 400 years. Not until 1858 did Britain launch the iron-hulled steamship SS Great Eastern (211 m). The modern record holder is the 1979 supertanker Seawise Giant (458 m), scrapped in 2010.

In an age without steel or steam, Zheng He’s fleet pushed wooden shipbuilding to its absolute limit—a testament to Ming engineering ambition.

How Did 27,000 Sailors Stay Organized? The Navy That Rivalled a City

Zheng He’s fleet was not a monolithic armada but a modular, multi-role task force:

- Treasure Ships (6–10): Diplomatic flagships carrying envoys, silk, and porcelain

- Horse Ships: Transported 200 warhorses for inland demonstrations of power

- Grain Ships: Carried 60+ tons of rice per vessel

- Troop Transports: Armed with early cannons, rockets, and matchlock guns

- Water Tankers: Dedicated freshwater supply ships. Managing the hydration and health of such a massive crew required a sophisticated logistics network.

With 27,800 personnel, roles were highly specialized:

- Command: Zheng He + Deputy Wang Jinghong

- Navigation: Firemasters (using star charts), helmsmen, depth sounders

- Support: 30+ doctors, interpreters (for Arabic, Swahili, Tamil), astrologers

- Logistics: Blacksmiths, carpenters, clerks, artists

This level of organization wouldn’t be matched until the 18th-century British Royal Navy.

What Made Ming Ships Unsinkable? China’s Secret Naval Tech

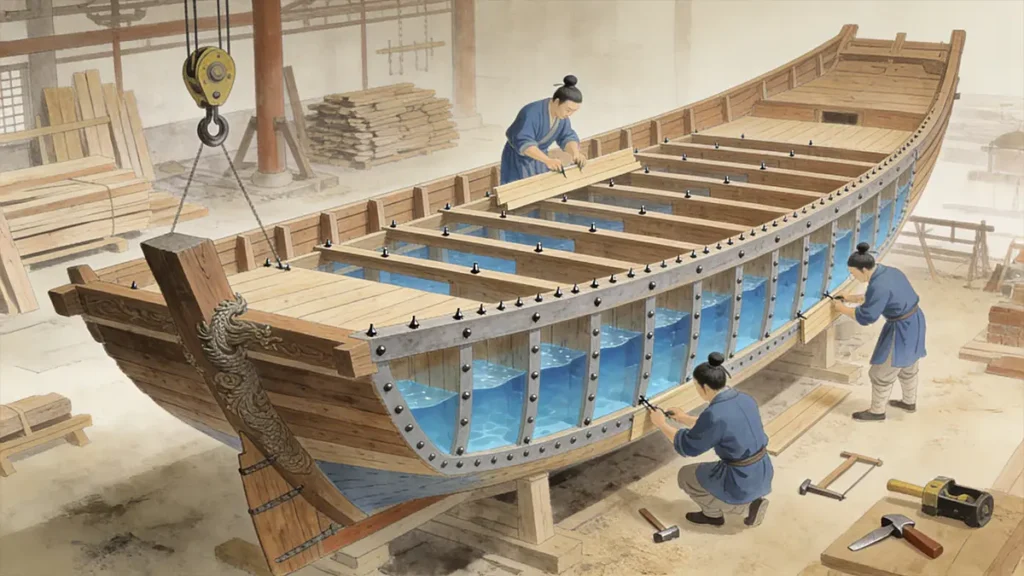

The Treasure Ships’ most revolutionary feature was watertight bulkheads—transverse wooden walls dividing the hull into sealed compartments. Even if two flooded, the ship remained buoyant.

This technology predated European adoption by 600 years. A 12th-century Song dynasty ship excavated in Quanzhou (1974) already had 13 watertight chambers. Cambridge University tests confirmed their remarkable survivability.

Other innovations:

- Balanced rudder and iron anchors: Reduced steering effort by 70%, allowing small crews to maneuver giants

- Junk rig: Bamboo-reinforced sails could be reefed sectionally—ideal for typhoons and tacking

- Flat-bottomed hull: Draft of only 4–5 meters, enabling access to rivers and shallow ports. By contrast, Columbus’s Santa Maria, despite being smaller, needed over 6 meters due to its deep keel.

These weren’t just ships—they were floating fortresses engineered for endurance.

How Did They Navigate Without GPS? Star Charts and Magnetic Compasses

By day, navigators used the “star-tracking board”—a set of 12 ebony rulers, each ~2.5 cm tall (≈1 finger-width), corresponding to 1 degree of latitude. Aligned with Polaris, it gave position within ±30 km.

In the Southern Hemisphere, they tracked Vega or the Canopy Star (part of Ursa Minor).

At night or in clouds, they relied on the magnetic compass, refined in the Ming era to 24 precise directions—far more accurate than earlier models.

Fleet coordination used:

- Day: Five-color flags (Red = anchor, Yellow = assemble)

- Night: Lantern codes (three red = emergency rendezvous)

- Fog: Gongs and conch shells

This system kept 200+ ships in formation across monsoon seas—a feat unmatched for centuries.

Beyond navigation, the sheer mechanical complexity of the fleet was a marvel of its own. To understand the physical mechanics behind their movement, explore how Ming Dynasty treasure ships worked across different sea conditions.”

How Did They Avoid Scurvy? The Bean Sprout Solution

While scurvy killed half of European sailors on long voyages, Zheng He’s fleet recorded almost no cases.

Their secret? Fresh mung bean sprouts, grown daily onboard in trays—rich in vitamin C.

Their diet also included:

- Sealed clay jars of rice and flour

- Ginger (anti-nausea), green tea (antibacterial), garlic (antimicrobial)

Medical care was advanced: 30+ physicians carried pharmacopeias like the Ruizhutang Prescriptions. In 1415, a feverish sailor was cured with Artemisia annua decoction—the same plant Tu Youyou would use 550 years later to win the Nobel Prize for malaria treatment.

Why Did China Burn Its Own Fleet? The Great Maritime Reversal

After Zheng He’s seventh voyage ended in 1433, the Ming Dynasty abruptly reversed course:

- Financial strain: Each expedition cost 2–3 million taels of silver—over 10% of state revenue (Ray Huang, Taxation in Ming China)

- Northern threats: The catastrophic Tumu Crisis (1449) saw 500,000 Ming troops annihilated by Mongols—defense funds shifted to the Great Wall

- Confucian backlash: Civil bureaucrats condemned ocean voyages as wasteful. In 1477, War Ministry official Liu Daxia ordered all Zheng He records burned to “prevent future emperors from repeating this folly.”

Why didn’t China sail to the Americas?

Technically possible—but strategically pointless. The Ming operated under the “tribute system,” where foreign kings acknowledged the emperor’s Mandate of Heaven (the divine right to rule) through symbolic gifts. The Americas had no states capable of participating in this ritual diplomacy—and no spices, gold, or strategic value compared to the Indian Ocean trade routes.

As the Book of Rites states: “Know where to stop, and you will find stability.”

It wasn’t inability—it was deliberate choice. The Ming saw the sea as a space for order, not conquest.

Where Are the Lost Treasure Ships? Hunting for Ming-Era Wrecks

Key evidence sites:

- Nanjing Longjiang Shipyard: 11m rudder post, 500m slipway, iron anchors

- Lamu Islands, Kenya: The Wamini people claim descent from Zheng He’s crew; DNA studies confirm East Asian paternal lineage

- Galle, Sri Lanka: The Trilingual Stele (1409) inscribed in Chinese, Tamil, and Persian records donations to Buddhist, Hindu, and Muslim sites—proof of Zheng He’s religious diplomacy (UNESCO verified)

Are any Treasure Ships still lost?

Yes. Ming Shi records that at least 12 ships sank off Sumatra during the final voyage. Marine archaeologists believe intact wrecks lie in the deep Indian Ocean—undisturbed due to depth and sediment.

If found, they’d rival Spain’s San José galleon—the “$20 billion shipwreck”—in historical significance.

FAQ (Frequently Asked Questions)

What Can the West Learn from Zheng He’s Peaceful Empire?

Zheng He’s voyages offer a radical alternative to the colonial narrative: power expressed through connection, not control.

While Europe would soon conquer the world with gunboats and greed, Zheng He brought porcelain, silk, calendars, and respect—and returned with giraffes, spices, and ambassadors.

Today, China’s 21st Century Maritime Silk Road echoes this legacy. And its decade-long anti-piracy patrols in the Gulf of Aden—conducted without occupying a single port—continue Zheng He’s tradition of peaceful presence.

The Treasure Ships may lie buried in Yangtze mud. But their message endures:

A civilization’s greatness lies not in how much land it conquers, but how many hearts it connects.

References:

- The Veritable Records of the Ming Dynasty (Zhonghua Book Company, 1974)

- Needham, Joseph. Science and Civilisation in China, Vol. IV (Cambridge University Press)

- Dreyer, Edward L. Zheng He: China and the Oceans in the Early Ming Dynasty (Oxford University Press, 2007)

- Huang, Ray. Taxation and Governmental Finance in Sixteenth-Century Ming China (Yale University Press, 1974)

- UNESCO: Galle Trilingual Stele Record

- China Ship Museum: www.china-ship-museum.org