Ming Treasure Ship vs. Santa Maria: How Big Was Zheng He’s Fleet Really?

The Ming Treasure Ship (Baochuan) commanded by Zheng He was vastly larger than Columbus’s Santa Maria, sparking a long-standing debate over its actual size and naval engineering.

Today, most Westerners know the story of Columbus crossing the Atlantic in 1492. Yet few realize that 87 years earlier, Zheng He—a eunuch admiral of China’s Ming Dynasty—had already led an astonishingly large fleet on seven voyages, reaching as far as the East African coast. At the heart of this fleet stood the Ming Treasure Ship, famously known in Chinese as Baochuan (“Treasure Vessel”). The gap between it and Columbus’s Santa Maria was far more than a matter of size; it reflected two civilizations’ fundamentally different understandings of the ocean.

So, just how large were Zheng He’s Treasure Ships? Are the figures recorded in historical documents reliable? To answer this question, we must turn to an official historical text compiled over 300 years ago.

The Astonishing Figures in the History of the Ming Dynasty

The most frequently cited source regarding the dimensions of the treasure ships is the Biography of Zheng He in the History of the Ming Dynasty (Ming Shi), compiled during the Qing Dynasty in 1739. It records: “Large vessels were constructed, measuring forty-four zhang and four chi in length, with sixty-two vessels measuring eighteen zhang in width.”

To put this in perspective: the zhang was a traditional Chinese unit of length. During the Ming era, one zhang equaled approximately 3.2 meters (about 10.5 feet). Using this conversion, the largest treasure ships would have measured roughly 137 meters (450 feet) long and 58 meters (190 feet) wide.

For reference: a modern soccer field is 105 meters long, and a Boeing 747 is about 70 meters from nose to tail. A 137-meter wooden ship would surpass both.

The same text also states that during Zheng He’s fourth voyage to the “Western Oceans” in 1413, he commanded “sixty-three treasure ships,” with a total fleet exceeding 200 vessels and carrying 27,800 personnel. This figure is corroborated by Ma Huan, a Muslim interpreter who sailed with Zheng He and later wrote Yingya Shenglan (“A Survey of the Ocean’s Shores”) around 1416.

These numbers are staggering—but they raise a critical engineering question: Could a wooden ship of that scale, built without iron frames or steel reinforcements, survive the open-ocean stresses of the Indian Ocean?

To find out, we need to leave the archives and head to the excavation site.

Archaeological Discoveries and Engineering Realities

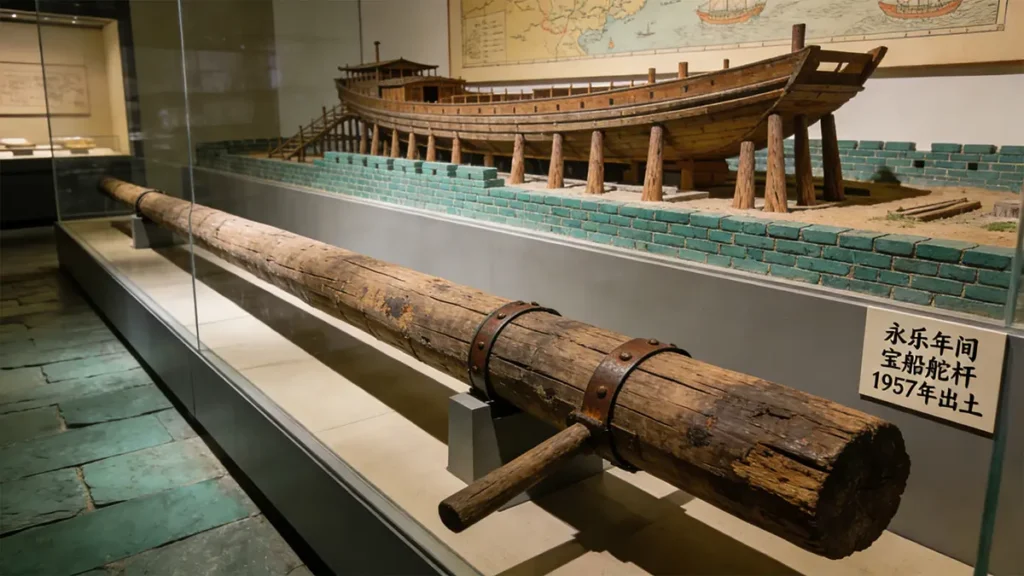

In 1957, workers at the Longjiang Shipyard in Nanjing unearthed a massive wooden rudder post—4.3 meters (14 feet) tall. This shipyard is explicitly named in the Veritable Records of the Ming as the construction site for Zheng He’s fleet, making this artifact the strongest physical evidence of the treasure ships to date.

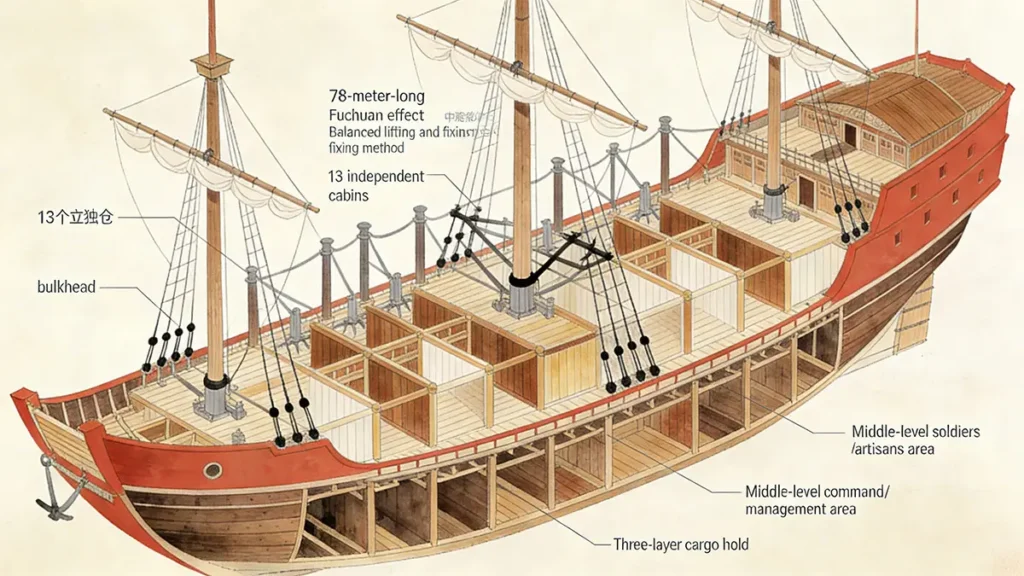

A team from Nanjing University, working with naval architects, used this rudder to estimate the ship’s true size. In traditional Chinese junks, rudder height typically ranges from 1/15 to 1/18 of the ship’s overall length. Applying this ratio, the vessel that carried this rudder would have been between 60 and 78 meters (197–256 feet) long.

This estimate aligns with principles of structural mechanics. Wood has natural limits in tensile and bending strength. Even with advanced Ming innovations—like watertight bulkheads and iron-reinforced joints—a wooden hull longer than 80 meters would flex dangerously in ocean swells, risking catastrophic failure.

Joseph Needham, the Cambridge historian, acknowledged Ming China’s maritime superiority in his landmark work Science and Civilisation in China (Vol. 4, Part 3), but called the 137-meter figure “almost certainly symbolic or exaggerated.” More recent scholarship supports this view. In her 2022 study Chinese Maritime Power in the Early 15th Century, Austrian sinologist Angela Schottenhammer concludes that 60–78 meters is the most archaeologically and mechanically plausible range.

So while the imperial records may have inflated dimensions for ceremonial effect, the real ships were still engineering marvels—just not mythical ones.

Now, let’s see how even this revised size compares to Columbus’s flagship.

The True Size of the Santa Maria

Unlike Zheng He’s fleet, no original hulls from Columbus’s ships survive. Our best estimates come from his logbooks, Spanish port inventories, and 19th-century reconstructions—such as the replica displayed at the 1992 Seville World Expo.

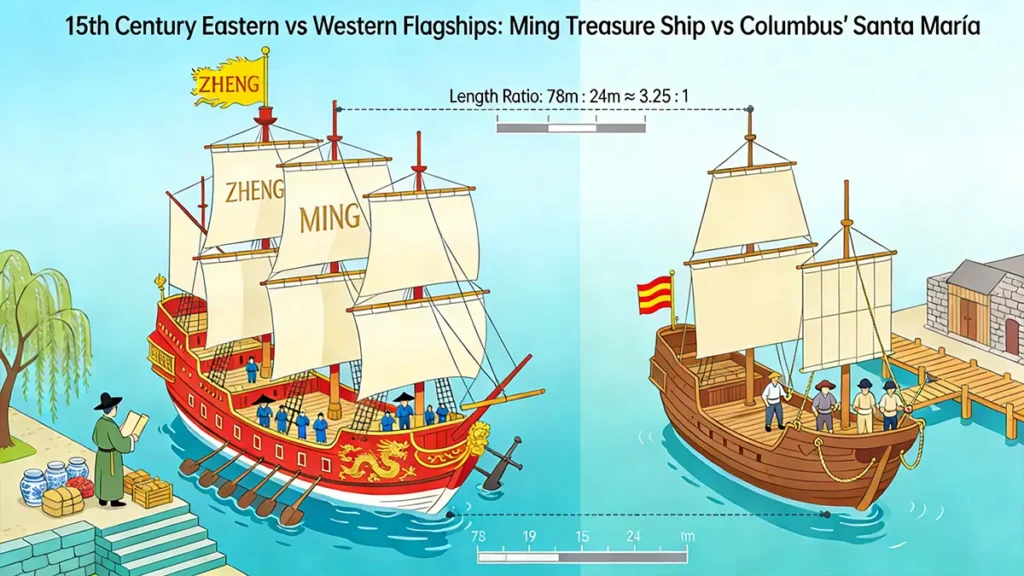

The Santa Maria was not a purpose-built exploration vessel. It was a nao—a slow, sturdy merchant ship adapted for transatlantic travel. Historians agree it measured about 24 meters (79 feet) long, 8 meters (26 feet) wide, displaced 100–150 tons, and carried a crew of roughly 40 men.

Columbus’s entire first fleet—Santa Maria, Pinta, and Niña—consisted of just three ships and about 90 men total.

Compare that to Zheng He’s 1413 expedition: over 200 ships and nearly 28,000 people. That’s not merely bigger—it represents a completely different order of state capacity and logistical ambition.

But raw numbers can feel abstract. To truly grasp the difference, imagine them side by side.

Visual Comparison: One Deck Could Hold an Entire Santa Maria

| Feature | Ming Treasure Ship (Realistic Estimate) | Santa Maria |

|---|---|---|

| Length | 60–78 m (197–256 ft) | 24 m (79 ft) |

| Width | 12–15 m (39–49 ft) | 8 m (26 ft) |

| Displacement | ~2,500–3,000 tons | ~100–150 tons |

| Crew per Flagship | 500–800 | ~40 |

| Total Fleet Size | 200+ ships, 27,800+ personnel | 3 ships, ~90 personnel |

Picture this: the entire Santa Maria could fit on the main deck of Zheng He’s Ming Treasure Ship—with room to spare. In fact, you’d need to line up three Santa Marias end-to-end to match the length of one treasure ship.

Scale models at the Nanjing Zheng He Treasure Ship Site Museum—based on the rudder post and shipyard foundations—confirm these proportions.

Yet the most striking contrast isn’t size—it’s purpose. Despite commanding overwhelming naval power, Zheng He never seized a single port. Why?

That question reveals the core difference between East and West in the Age of Discovery.

Peaceful Voyages vs. Colonial Expansion: Two Visions of the Sea

Zheng He’s expeditions were funded by the Yongle Emperor to “spread virtue and win over distant peoples”—a Confucian ideal emphasizing moral influence over military force. His fleet brought back giraffes (mistaken for the mythical qilin), spices, and foreign envoys, but never settlers, soldiers, or colonial administrators.

In stark contrast, Columbus sailed under a royal contract with Spain that granted him 10% of all profits from new lands and the title of viceroy over any territory he claimed. His mission was economic and territorial from the outset.

As historian Felipe Fernández-Armesto writes in Pathfinders: A Global History of Exploration: “Zheng He’s armada was the world’s first ‘soft power’ projection—impressive, peaceful, and ultimately unsustainable in a world moving toward empire.”

When the Ming court halted the voyages in 1433—citing cost, internal politics, and a shift toward agrarian conservatism—they weren’t falling behind. They were choosing a different path.

But that choice had consequences. Within 60 years, smaller European fleets, driven by profit and conquest, would dominate global sea lanes. The treasure ships vanished from memory—until archaeology brought them back.

So how should we weigh myth against reality?

Myth vs. Reality—And Why Both Matter

Yes, the 137-meter figure is almost certainly inflated. No known wooden ship in history has approached that length and remained seaworthy. The Wyoming, a six-masted schooner launched in 1909 at 107 meters, leaked so badly that constant pumping was required to keep her afloat until she foundered in 1924.

But dismissing Zheng He because of exaggerated numbers misses the point. Even at 78 meters, the Ming Treasure Ship was the largest wooden seagoing vessel of the pre-industrial world. And unlike European ships of the time, it featured innovations like:

Watertight compartments—described by Marco Polo in the 13th century as a reason Chinese ships “do not sink easily”

Balanced, retractable rudders that could be raised in shallow waters

Multiple masts with lug sails allowing precise control in crosswinds

These weren’t brute-force giants—they were intelligently engineered systems.

The real wonder isn’t that China built a 450-foot phantom. It’s that it built a 250-foot peacekeeping fleet that reached Kenya in 1418—without firing a single shot.

Which brings us to a final puzzle: if Zheng He’s achievements were so great, why don’t more people know about them?

Why Zheng He Was Forgotten—and Why He’s Being Rediscovered

For centuries, Eurocentric historiography framed global exploration as a European achievement. Textbooks from London to Boston celebrated Columbus, Magellan, and Cook—but rarely mentioned Zheng He.

Even today, a Google search for “largest wooden ship in history” often omits Chinese vessels entirely. Yet institutions like the British Library now digitize Zheng He’s navigation maps, and UNESCO recognizes his voyages as part of shared human heritage.

Part of the silence stems from China itself. After 1433, the Ming dynasty destroyed most fleet records and imposed strict sea bans. The treasure ships became legend—then myth—then forgotten.

But thanks to archaeology, engineering analysis, and global historical revisionism, Zheng He is returning to the world stage—not as a nationalist symbol, but as proof that global connection once existed without conquest.

And that’s a story worth telling—accurately.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQ)

A Fleet That Changed History—Without Firing a Shot

The Ming Treasure Ship may not have been 137 meters long. But at 60–78 meters, it was still the most impressive wooden vessel of the pre-industrial world. Paired with a fleet larger than any European navy of the time, it represented a vision of global engagement based on diplomacy, not domination.

Columbus’s Santa Maria changed the world through conquest. Zheng He’s fleet showed another way was possible.

In an age rethinking colonial narratives, perhaps it’s time we gave equal weight to the admiral who sailed farther—with more ships, more people, and no guns.

Sources & Further Reading:

Ming Shi (History of Ming), Chapter 304 – Chinese Text Project

Ma Huan, Yingya Shenglan (1416) – Translated by J.V.G. Mills (Hakluyt Society)

Needham, Joseph. Science and Civilisation in China, Vol. 4, Part 3 (Cambridge University Press)

Schottenhammer, Angela. “Chinese Maritime Power in the Early 15th Century,” Maritime China, 2022

Nanjing Zheng He Treasure Ship Site Museum – Official Site

Fernández-Armesto, Felipe. Pathfinders: A Global History of Exploration (W.W. Norton, 2006)