The Secrets of Celestial Navigation: How Zheng He’s Fleet Conquered the Seas

Zheng He’s fleet achieved precise transoceanic voyages across the Indian Ocean without modern instruments by using an advanced Chinese system of celestial navigation, combined with the water compass, monsoon knowledge, and detailed nautical charts¹.

This was not merely a technological marvel—it was the culmination of 15th-century global maritime wisdom.

In 1405, Zheng He’s treasure fleet departs from Longjiang Port in Nanjing. The massive Ming-era treasure ship looms against the morning mist of the Yangtze River, crewed by sailors in authentic early 15th-century attire.

Why Did Zheng He’s Fleet Never Get Lost?

Between 1405 and 1433, Zheng He led seven monumental expeditions, reaching as far as the east coast of Africa. His fleet visited more than thirty countries, covering tens of thousands of kilometers, yet rarely missed its intended ports².

At the same time, European ships still hugged Mediterranean shorelines, relying on visible landmarks. True open-ocean navigation remained beyond their reach³.

The critical difference? Zheng He’s team had mastered a complete system of celestial navigation—using star positions to determine latitude and enabling direct crossings of vast ocean basins.

So how did it actually work?

The Kamal Mystery: How Could a Wooden Plate Measure the Stars?

The most essential tool in the hands of Zheng He’s chief navigators—known as huo zhang (literally “fire chiefs,” a Ming-era title for shipboard leaders)—was not a complex instrument, but a simple set of ebony plates called the “star-sighting board.”

The set contained 12 pieces, graded from large to small, each edge marked in units called zhi (literally “fingers”), where 1 zhi ≈ 1.9°⁴.

To use it, the navigator stood on the rolling deck, holding one end of the plate against his brow while aligning the other with the North Star. He slowly lowered it until the bottom edge met the horizon. The zhi value of the plate used at that moment corresponded to the local latitude. For example, at 30°N (such as Hangzhou), the reading was about 16 zhi; near the equator, it approached zero⁵.

Though seemingly rudimentary, this method was remarkably effective. More importantly, it was not invented in isolation. Arab sailors in the Indian Ocean had long used a similar device called the kamal—a knotted cord held in the teeth at one end, with the other aligned to a star. The angle was estimated by the length of cord between the eye and the knot⁶.

Evidence of cross-cultural exchange abounds: an Islamic astrolabe from the Yuan dynasty was unearthed in Quanzhou, and Ma Huan’s Yingya Shenglan mentions collaboration with “foreign pilots” (fan huo zhang)⁷. Zheng He’s team likely synthesized Arab, Persian, and Chinese navigational knowledge.

What made the Chinese approach unique was its standardization: these techniques were codified into official manuals and deployed as part of a state-coordinated maritime system.

Beyond the Compass: What Made the Chinese “Water Compass” So Stable?

The magnetic compass originated in China, but Ming sailors refined it for ocean use.

Instead of mounting a dry needle on a pivot—as Europeans did—they threaded a slender magnetized needle through a lightweight lampwick and floated it in a bowl of still water. When the ship rocked, the water absorbed vibrations. The lampwick swirled gently with the waves, but the needle remained steady, pointing reliably north⁸.

This “water compass” proved vital in stormy seas like the South China Sea. In contrast, contemporary European dry compasses often spun wildly during heavy motion⁹.

Yet even the best compass couldn’t answer two basic questions: How fast are we moving? And how much time has passed?

No Clock, No GPS: How Did They Track Speed and Time?

Without mechanical clocks, Zheng He’s fleet devised clever analog methods.

One was the wooden-slip technique: a small chip of light wood was dropped from the bow. A sailor silently counted breaths—or recited a fixed phrase—until the chip reached the stern. Knowing the ship’s length, they could estimate speed.

Another was the incense-timer method: specially calibrated incense sticks were burned at sea. Each stick took about 30 minutes to burn completely, marking a standard sailing interval¹⁰.

These approximations, when combined with celestial fixes, allowed surprisingly accurate voyage planning.

But even perfect navigation requires a seaworthy hull—which brings us to another Chinese innovation long overlooked in the West.

The Secret Compartment: How Did Zheng He’s Ships Survive Storms?

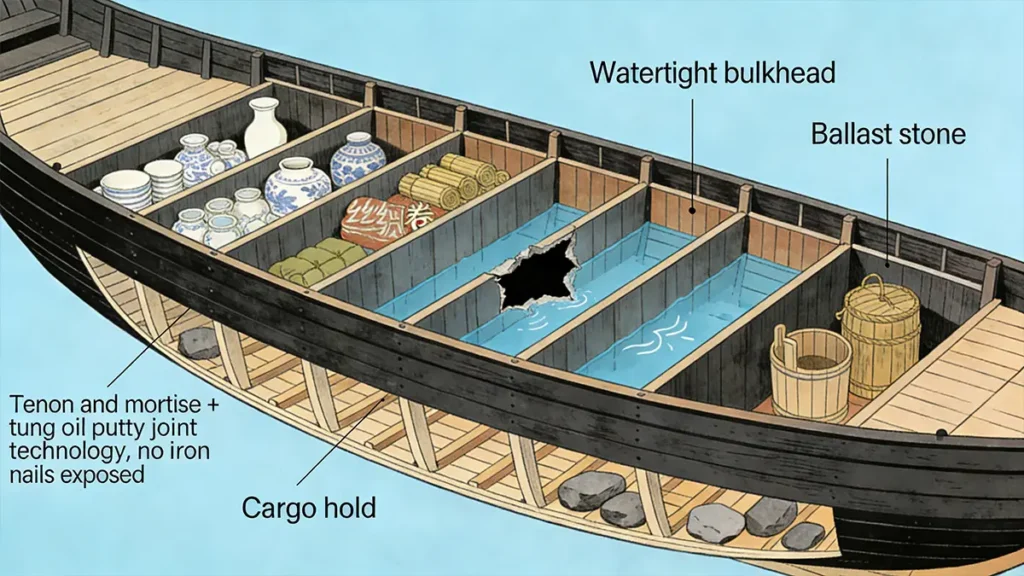

In 1415, a supply ship from Zheng He’s fleet struck heavy seas near Sumatra. Its hull cracked and began flooding. By all logic, it should have sunk quickly.

It didn’t—because its interior was divided into multiple watertight compartments by transverse bulkheads¹¹.

Even if one section filled with seawater, the others retained buoyancy, buying crucial time for repairs. This design dramatically improved survival odds in open-ocean emergencies.

A Ming-era Fujian junk model in the British Museum clearly shows this feature¹². The British Royal Navy wouldn’t adopt watertight compartments in warships until the 18th century¹³.

This “shipbuilding breakthrough” was key to Zheng He’s confidence in commanding fleets of 27,000 people across unpredictable seas.

Mapping the Unknown: How Did They Navigate Without Modern Charts?

The real challenge lay in uncharted waters. The Indian Ocean’s monsoons follow a strict rhythm: southwest winds blow from May to September (ideal for outbound voyages); northeast winds dominate from November to March (perfect for return trips)¹⁴. Miss this window, and a ship could be stranded overseas for a year.

To manage this complexity, Zheng He’s team produced the Mao Kun Map—now held at Oxford’s Bodleian Library. This scroll charts over 500 locations and includes notes like “here, the North Star appears at X zhi”¹⁵. It wasn’t decorative—it was an executable navigation database.

Even more impressive was logistics: how did they coordinate food, fresh water, medicine, and diplomatic gifts—including live horses—for 27,000 people?

The answer: a modular fleet system with synchronized timetables. Supply ships, war junks, and treasure vessels converged at hubs like Malacca and Calicut on prearranged dates—a level of national-scale coordination unmatched anywhere else in the 15th century.

And it all rested on one certainty: they always knew where they were. That is the true power of celestial navigation.

Frequently Asked Questions About Celestial Navigation

To deepen understanding, here are three common questions:

References

¹ Needham, J. (1971) Science and Civilisation in China, Vol. 4, Part 3: Civil Engineering and Nautics. Cambridge University Press, p. 596.

² Dreyer, E.L. (2007) Zheng He: China and the Oceans in the Early Ming Dynasty, 1405–1433. Pearson, pp. 50–55.

³ Taylor, E.G.R. (1956) The Haven-Finding Art: A History of Navigation. London: Hollis & Carter, p. 89.

⁴ Needham (1971), p. 598.

⁵ Ibid., p. 600.

⁶ “Kamal (navigation)” (n.d.) Wikipedia. Available at: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Kamal_(navigation)(Accessed: 28 January 2026).

⁷ Ma, H. (1416) Yingya Shenglan [The Overall Survey of the Ocean’s Shores]. Modern annotated edition, Zhonghua Book Company, 2005.

⁸ Needham (1971), p. 602.

⁹ Gardiner, R. (1994) Cogs, Caravels and Galleons. Conway Maritime Press, p. 45.

¹⁰ Ma (1416), Chapter 3.

¹¹ Schottenhammer, A. (2008) The East Asian Mediterranean: Maritime Silk Road and Cultural Exchange. Harrassowitz Verlag, p. 112.

¹² British Museum Collection Online. Object ID: MAS.618. Available at: https://www.britishmuseum.org/collection (Accessed: 28 January 2026).

¹³ Gardiner (1994), p. 78.

¹⁴ Dreyer (2007), p. 62.

¹⁵ Mills, J.V.G. (trans.) (1970) Ma Huan: Ying-yai Sheng-lan – The Overall Survey of the Ocean’s Shores. Cambridge University Press, Appendix: The Mao Kun Map.

¹⁶ Ming Shilu (Veritable Records of the Ming Dynasty), Xuangzong reign, juan 114, 1433.

¹⁷ U.S. Naval Academy. (2025) Navigation Curriculum Overview. Available at: https://www.usna.edu/Academics/Majors-and-Courses/course-details.php?course=NA221

¹⁸ Bowditch, N. (2022) American Practical Navigator, Vol. I. National Geospatial-Intelligence Agency, Ch. 11.