The Technical Secrets of Longjiang Shipyard: Supporting Zheng He’s Seven Voyages

In the early 15th century, while Europe was still building coastal fishing boats, China was mass-producing hundred-meter-long treasure ships at a “Ming Dynasty super factory.” Ninety years ahead of Europe, it utilized tide-powered dry docks and bamboo-inspired internal structures to support 137-meter wooden vessels. Why did the world later forget this feat? Read on to discover how an industrial marvel buried in mud for five centuries was unearthed.

In 1405, a fleet of 317 ships set sail from Nanjing toward the Indian Ocean. According to the History of the Ming, the flagship treasure ship measured 44 zhang and 4 chi—approximately 137 meters—over five times the length of Columbus’s Santa Maria (about 25 meters). Carrying over 27,000 people—including soldiers, translators, physicians, astronomers, and diplomatic envoys—this fleet’s scale and organizational complexity far surpassed any contemporary maritime power.

Yet what was truly awe-inspiring was not the fleet itself, but the industrial powerhouse behind it: the Longjiang State Shipyard on the south bank of the Yangtze River in Nanjing. This was no romanticized “ancient marvel,” but a 15th-century mega-factory—a national engineering system integrating resource mobilization, standardized production, and cutting-edge R&D.

Joseph Needham, a Cambridge biochemist turned historian of science, wrote in his seven-volume magnum opus Science and Civilisation in China: “The shipbuilding techniques of Ming China, in scale, organization, and technology, were at least two centuries ahead of the rest of the world.” He specifically noted that Zheng He’s fleet relied not on individual heroism, but on a “highly rationalized national industrial system.”

Today, this site is a residential area and park in Nanjing’s Gulou District. Yet during the Yongle era (1402–1424), it was the world’s most advanced “maritime industrial base.” To understand how Zheng He’s voyages became possible, one must explore this forgotten Ming-era “SpaceX.”

First, let’s clarify its internal structure: Who handled mass production? Who drove breakthroughs?

Mass Production Base vs. Cutting-Edge Project Department: The Ming Dynasty’s “Dual-Track Supply Chain System”

Many sources treat “Longjiang Shipyard” as a single entity, yet this obscures its true organizational ingenuity. According to the 2006 Archaeological Excavation Report on the Longjiang Shipyard Site published by the Nanjing Museum, Ming Nanjing actually operated a dual-track shipbuilding system:

| Dimension | Longjiang Administration Shipyard (Mass-Production Facility) | Treasure Ship Yard (The Skunk Works) |

|---|---|---|

| Established | Early Hongwu reign (post-1368) | Yongle 3rd year (1405) |

| Function | Standardized warships & transport vessels (200+ per year) | Custom-built ocean-going treasure ships (giant, high-spec) |

| Core Mission | Standardization (replicable, efficient) | Pushing the Envelope (technological frontier) |

| Management | Ministry of Works; fixed procedures | Eunuch-directorate; priority resource allocation |

| Labor Force | Hereditary artisan households ensuring generational skill transmission | Top craftsmen drafted nationwide |

This division parallels the coexistence of conventional production lines and Lockheed Martin’s famed Skunk Works in modern aerospace. The Longjiang Administration Shipyard ensured daily naval operations, while the Treasure Ship Yard concentrated resources on breaching the physical limits of wooden shipbuilding—such as constructing 137-meter behemoths like Zheng He’s treasure ships.

But a question remains: Was such an enormous wooden vessel physically feasible? Western scholars have long questioned its structural integrity, arguing it would suffer “hogging” (midsection arching upward while ends sink), leading to fracture. To answer this, we must examine the ship’s internal architecture.

How Does a 100-Meter Wooden Ship Avoid Breaking? The Mechanical Truth Behind Watertight Bulkheads

Western naval engineers have long debated: Could a 137-meter all-wooden ship survive without snapping under wave stress? This skepticism holds—if the hull were a hollow cylinder.

But Ming treasure ships defied this assumption. Their secret lay in watertight bulkheads (Internal Cellular Structure).

Imagine a giant bamboo stalk: hollow externally, yet remarkably strong. Why? Because internal nodes segment the tube, distributing stress and preventing buckling. These “bamboo nodes” transform fragility into resilience.

Treasure ships applied the same principle. Archaeological and textual evidence shows the hull was divided by 12 to 16 transverse bulkheads, spaced just 2–3 meters apart, extending from keel to deck. These were not merely watertight compartments—they functioned as internal structural ribs.

In materials science, a beam’s bending stiffness scales with its sectional moment of inertia. By inserting dense bulkheads, Ming craftsmen unintentionally created a box girder architecture, dramatically boosting longitudinal stiffness. This allowed the ship to resist hogging deformation across ocean swells.

The 1974 Quanzhou Southern Song shipwreck had 13 compartments; Zheng He’s ships were larger and more densely partitioned. This design predated Europe by over 400 years—the British Royal Navy only adopted similar structures in the 18th century.

This explains how treasure ships crossed the Indian Ocean intact. But strength alone isn’t enough—you must also steer it.

Dry Docks: Low-Cost, High-Intelligence Engineering Harnessing Tides

Skeptics often ask: “Even if the design worked, did the Ming have docks large enough?”

The answer lies beneath Nanjing’s soil. In 2004, archaeologists uncovered six zuotang (tidal enclosures)—essentially tide-powered dry docks. The largest measures 500 meters long, 40 meters wide, and 6 meters deep, with wooden-pile-reinforced floors and winch foundations on both sides—large enough to build three 130-meter ships side by side.

Even more ingenious is its operation: fully powered by natural tides.

Workflow:

- At high tide, floodgates open—river water fills the basin.

- Ships enter and anchor in place.

- Gates close; as the tide recedes, water drains out.

- Hulls settle on the dry floor, allowing workers to repair keels, replace rudders, or inspect planking from below.

This is low-tech, high-intelligence engineering: no pumps, no engines—just mastery of hydrology. It represents the pinnacle of pre-industrial systems thinking.

This technology predates Europe’s first dry dock (Lisbon, 1495) by nearly 90 years. Longjiang thus became the world’s first industrial complex with large-scale dry docking capability.

With infrastructure, structure, and organization in place, the fleet’s technical brilliance could flourish. Next, we dissect the five core technologies that made it all possible.

Five Core Technologies: A Pre-Industrial Systems Engineering Marvel

Building a 137-meter wooden ship wasn’t about stacking timber—it required solving five fundamental challenges:

How to prevent structural failure?

How to maneuver a colossus?

How to harness wind efficiently?

How to stay watertight under stress?

How to preserve wood for decade-long voyages?

Ming craftsmen answered with five synergistic innovations—not isolated tricks, but an integrated maritime engineering ecosystem.

1.Structural Ribs: How Watertight Compartments Prevent Fracture

Problem: Western engineers doubted a 137m wooden hull could resist “hogging” without breaking—valid for hollow tubes.

Ming Solution: 12–16 transverse bulkheads, spaced 2–3m apart, from keel to deck, acting as internal structural ribs.

Engineering Principle: The compartmentalized hull formed a box girder, maximizing longitudinal stiffness. This distributed bending stress across the entire frame.

Evidence: The 1974 Quanzhou wreck had 13 compartments; Zheng He’s ships were larger and denser. Europe didn’t adopt this until the 1700s.

This explains ocean-crossing durability. But control demands more than strength.

2.The Balanced Rudder: Steering a 140-Meter Ship with Six Men

Problem: Larger rudders require immense force to turn.

Ming Solution: In 1957, an 11.07-meter rudder post was unearthed in Nanjing (now in the National Museum of China) [2]. Proportional to a 120–140m ship.

The genius? The rudder blade was partially forward of the pivot axis—a balanced rudder (hydrodynamically assisted). Water pressure during turns generated counter-torque, slashing required manpower.

Operation: Connected to a winch, 4–6 sailors could steer. Even better: the rudder was height-adjustable—raised in shallow ports, lowered in deep sea for stability.

European Contrast: Contemporary ships used unbalanced stern rudders. Balanced rudders only became common in the West in the 19th century.

3.Multi-Mast Sail System: Flexible Wind Capture Across Monsoon Zones

Problem: The Indian Ocean features seasonal monsoons—reliable but unidirectional winds.

Ming Solution: Treasure ships featured nine masts carrying twelve square sails, each independently adjustable via bamboo battens.

Unlike European rigid sails, Ming sails used horizontal bamboo rods sewn into the canvas, allowing sailors to roll, tilt, or reef sections like Venetian blinds—maximizing thrust in variable winds.

Result: Ships could tack effectively and maintain speed even during monsoon transitions—a critical advantage for round-trip diplomacy.

4.Caulking Technology: Keeping Seams Tight for Years

Problem: Wood expands and contracts with humidity and temperature, opening seams.

Ming Solution: After fitting planks with mortise-and-tenon joints, workers stuffed seams with hemp fiber soaked in tung oil and lime—a natural polymer sealant.

Tung oil oxidizes into a waterproof film; lime acted as a filler and antifungal agent. This mixture remained elastic for years, adapting to hull movement without cracking.

Durability: Historical records note ships undergoing only minor caulking repairs after multi-year voyages.

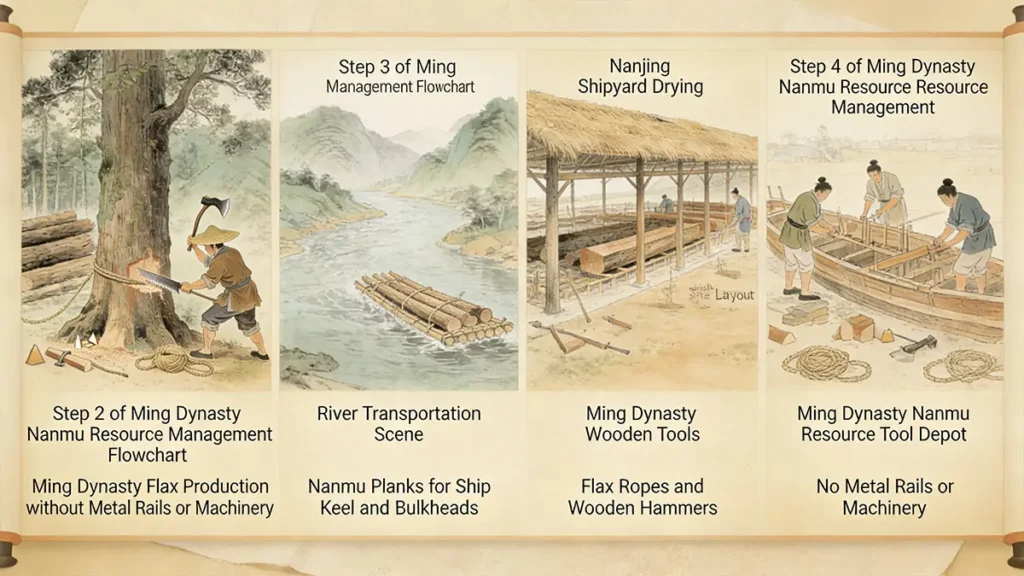

5.Nanmu Life Management: Full-Cycle Control from Forest to Keel

Problem: Freshly cut timber contains high moisture, leading to warping, cracking, or decay during long voyages.

Ming Solution: Treasure ships were primarily built from Chinese nanmu (Phoebe zhennan), a dense, aromatic, decay-resistant hardwood sourced from pristine forests in Sichuan and Guizhou. After felling, logs were immediately debarked and stored in ventilated sheds for 2–3 years of shaded air-drying. The Ming-era Treatise on the Arts of Industry emphasized: “Fresh wood is heavy with moisture; it must be dried for three years before use.”

Preservation Treatment: Analysis of iron nails recovered from the Longjiang River in 2010 revealed traces of arsenic and mercury, suggesting the wood may have been treated with mineral-based preservatives to deter insects and fungal decay—a sophisticated form of pre-modern anti-fouling technology.

Resource Assurance: The early Ming court enacted strict logging bans in key nanmu regions, creating a state-managed sustainable forestry system. This centralized resource strategy ensured a steady supply of premium timber—far surpassing Europe’s fragmented, market-driven timber practices.

Each of these five technologies stands as a masterpiece on its own. But their true genius lies in systemic integration—forming a closed-loop maritime industrial ecosystem stretching from mountain forests to tidal dry docks. Yet this entire system vanished almost overnight due to a single political decision.

Sudden Silence: From Global Expansion to Isolationism

In 1433, Zheng He returned from his seventh and final voyage. Shortly after, the Ming court executed a dramatic policy reversal—abandoning the Confucian maritime ideal of “xuān dé huà ér róu yuǎn rén” (“projecting virtue to pacify distant peoples”) in favor of maritime prohibition (haijin) and inward-looking isolationism.

The consequences were catastrophic for China’s naval legacy:

- Official treasure ship blueprints were ordered destroyed;

- Ocean-going voyages were banned by imperial decree;

- The Longjiang Shipyard was decommissioned and left to decay.

More fatally, wooden structures rotted rapidly in Nanjing’s humid climate, and archival records were lost amid bureaucratic neglect and later political turmoil. The world’s most advanced pre-industrial maritime system thus sank into historical oblivion.

As the Ming Dynasty burned its ship plans and sealed its ports, Europe stood on the brink of the Age of Discovery. This pivot didn’t just end an era—it quietly reshaped the global balance of power for the next 500 years.

It wasn’t until the mid-20th century, when an 11-meter-long rudder post was unearthed in Nanjing, that the world began to rediscover the astonishing engineering sophistication of 15th-century China.

Archaeological Evidence: Industrial Truths Unearthed Underground

- 1957: An 11.07-meter rudder post discovered in Xiaguan, Nanjing (National Museum of China, Inv. No. NM-1957-032) [2]

- 2004–2005: Nanjing Museum excavated six zuotang (tidal enclosures), tool pits, and timber yards, uncovering iron anchors (2.7 tons), ship nails (up to 32 cm long), wooden mallets, chisels, and caulking tools [1]

- Carbon-14 dating: Nanmu wood fragments dated to 1400–1430 CE, precisely matching Zheng He’s active years [5]

These artifacts do more than confirm the existence of treasure ships—they reveal a highly organized, state-coordinated pre-modern industrial complex operating at scale.

What Else Can You See at Nanjing’s Ming Dynasty Sites?

If ancient industrial systems intrigue you, visit the Nanjing Treasure Shipyard Site Park (Address: Sancha River, Gulou District, Nanjing)—one of the most compelling testaments to Ming engineering prowess.

Highlights include:

- A 1:1 scale replica of a conservative-engineering-reconstruction treasure ship (71 meters long)

- Dry Dock Ruins Exhibition Area with a glass walkway overlooking the 500-meter embankment

- Excavated Artifacts Hall featuring the original rudder post, iron anchors, and shipbuilding tools

Access: Take Metro Line 4 to Longjiang Station, then walk 10 minutes. Best visited in spring or autumn—avoid summer’s rainy season.

Standing at the edge of the ancient moat, you won’t encounter myth—you’ll sense the tangible reality of an empire built not on legend, but on institutional systems, technological integration, and deep ecological wisdom.

Quick Q&A (FAQ)

Notes and Authoritative Sources

- [1] Nanjing Museum, “Brief Report on the 2004–2005 Archaeological Excavation of the Nanjing Longjiang Shipyard Site,” Wenwu (Cultural Relics), No. 5, 2006.

- [2] National Museum of China official website, Collection Item “Ming Dynasty Rudder Post,” Catalog No. NM-1957-032: https://www.chnmuseum.cn

- [3] Xi Longfei, Research on Zheng He’s Treasure Ships, People’s Communications Press, 2003, p. 87.

- [4] Jiangsu Provincial Institute of Archaeology, Analysis Report on Metals and Timber Unearthed at Longjiang Shipyard, 2010.

- [5] Institute of Geology and Geophysics, Chinese Academy of Sciences, Radiocarbon Dating Report on Timber from the Nanjing Longjiang Shipyard Site, 2006.

- [6] Joseph Needham, Science and Civilisation in China, Vol. 4, Part 3: Civil Engineering and Nautics, Cambridge University Press, 1971.

- [7] Angela Schottenhammer, The Maritime Silk Road, Harrassowitz Verlag, 2008.

- [8] Nanjing Municipal Bureau of Culture and Tourism, Official Introduction to “Treasure Shipyard Site Park”: http://whly.nanjing.gov.cn