The Engineering of the Ming Fleet: Why Teak and Oak Made the Treasure Ships Unsinkable

On the global shipbuilding landscape of the 15th century, East and West followed radically different technological paths. Europe relied on oak to construct sturdy but vulnerable single-hull ships; in contrast, Ming Dynasty China utilized teak, nanmu, and cypress, along with watertight compartments, to create a robust “redundant” survival system. This deep understanding of shipbuilding materials and structural principles made Ming Dynasty vessels the most reliable ocean-going platforms of their time.

These two approaches embodied a fundamental clash of engineering philosophies:

- Europe focused on concentrated strength—using the hardest wood (oak) to resist external forces, but collapsing completely upon damage;

- China prioritized systemic resilience—using durable materials (teak) to extend service life, watertight compartments to contain flooding, and flexible structures to absorb dynamic stress.

This divergence ultimately determined who could truly “survive” the open ocean.

So how did this system function? And why did Ming treasure ships endure Indian Ocean storms and reefs with almost no recorded sinkings due to structural failure?

Teak and Oak: Two Woods, Two Maritime Fates

For 15th-century European shipbuilders, oak was the cornerstone of maritime power. Its hardness and density made it ideal for short voyages across the North Sea and Atlantic. Yet oak possessed a fatal flaw: it could not withstand long-term marine erosion on its own. More critically, European ships used a single-hull design. Once the hull was breached, water flooded the entire vessel, causing rapid sinking. Historical records indicate that a typical oak merchant ship operating in tropical waters rarely lasted more than 10 years (UNESCO, Maritime Silk Road Thematic Study, 2017).

Meanwhile, Ming engineers faced an entirely different challenge: three-year round-trip voyages across the Indian Ocean, with no access to repair ports. Their ships had to survive biological corrosion, monsoon storms, grounding, and even combat damage—yet still return safely to China. To meet this demand, they rejected reliance on any single “strongest wood” and instead developed a tiered material system.

Archaeological and textual evidence shows that critical components of Zheng He’s treasure ships—such as the rudder stock, keel, and deck—were built using teak (Tectona grandis). This tropical hardwood possesses two key natural defenses:

- High natural oil content (teak oil), which creates a hydrophobic barrier against moisture;

- Silica deposits (≈0.5%), which dramatically increase surface hardness and deter shipworms (Teredo navalis) from boring into the wood (Schmidt et al., Wood Science and Technology, 2018).

Laboratory tests confirm that teak can resist decay in saltwater for 50 to 100 years—two to three times longer than untreated oak under comparable conditions.

However, a common misconception must be addressed: Ming ships did not use European oak. China lacks native species of high-quality shipbuilding oak. The Ming-era technical manual Tiangong Kaiwu explicitly states: “For all ships… the keel uses nanmu, the sides use shanmu (Chinese fir).” Here, nanmu refers to Phoebe zhennan, a native Chinese hardwood with a density of 0.6–0.7 g/cm³ and a bending strength of approximately 80 MPa—comparable to oak in structural performance, yet far more accessible.

Thus, the phrase “teak and oak” should not be read literally. Instead, it symbolizes two complementary engineering roles: teak provided long-term durability against biological threats, while nanmu (functionally analogous to oak) delivered structural rigidity. This strategic material division proved far more efficient—and far better suited to transoceanic voyages—than Europe’s monolithic reliance on oak.

Teak, Oak, and Nanmu: Key Performance Comparison

| Property | Teak (Tectona grandis) | Oak (Quercus robur) | Nanmu (Phoebe zhennan) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Density (g/cm³) | 0.65–0.75 | 0.60–0.90 | 0.60–0.68 |

| Natural Oil Content | High | Low | Medium |

| Compressive Strength (MPa) | ≈100 | ≈110 | ≈80 |

| Silica Content | High (≈0.5%) | Low | Low |

| Service Life in Seawater | 50–100 years | 20–40 years | 30–60 years |

Materials solved the “time” problem—resisting corrosion and biofouling. But surviving sudden impacts required a revolutionary internal design.

Watertight Bulkheads: A Safety Innovation 400 Years Ahead of Its Time

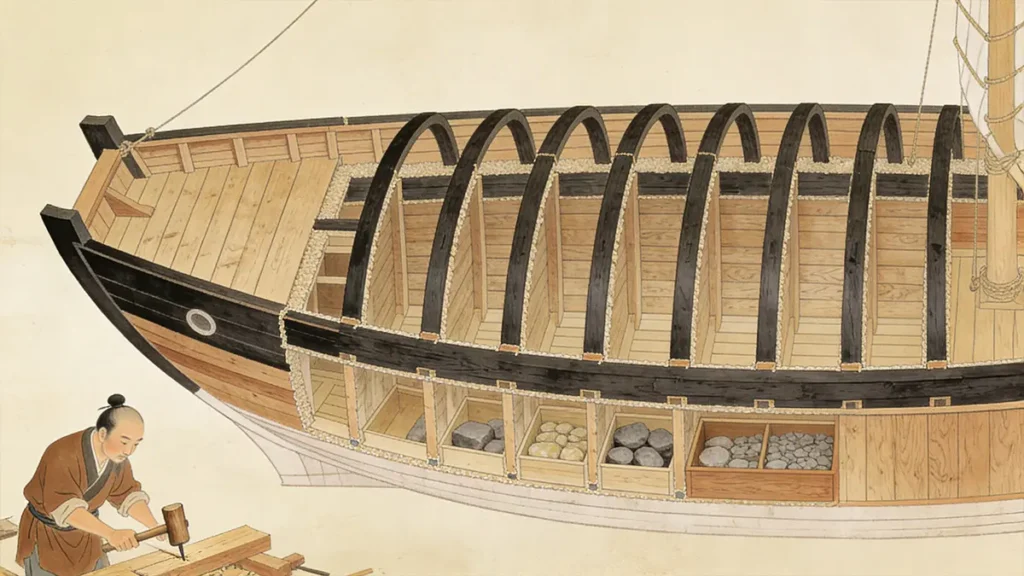

Imagine a bamboo stalk: even if one segment cracks, the rest remain intact. Ming shipbuilders applied this biomimetic principle to naval architecture through the invention of watertight bulkheads.

According to Ma Huan’s eyewitness account in Yingya Shenglan (The Overall Survey of the Ocean’s Shores), treasure ships were divided into 9 to 16 independent, sealed compartments by vertical bulkheads. Each bulkhead—15 to 30 centimeters thick—was carved from solid nanmu. Seams were caulked with an ancient “super adhesive”: a mixture of tung oil, lime, and hemp fibers. This compound expanded upon contact with water, improving its seal over time (Li, Chinese Shipbuilding and Maritime Technology, 2004).

The engineering logic was clear: if the hull was punctured in one section, only that compartment would flood. The others retained full buoyancy. Simple calculations illustrate this: assuming one compartment holds 50 m³ of water, flooding would reduce buoyancy by ~50 tons. Yet a fully loaded 70-meter treasure ship displaced about 3,000 tons—meaning the remaining 15 compartments could still provide over 2,900 tons of lift, far exceeding the ship’s own weight.

This concept did not appear in European shipbuilding until 1795, when British engineer John Elder introduced it to merchant vessels—nearly 400 years after Zheng He’s voyages (Bass, A History of Seafaring, Thames & Hudson, 1977). Before then, a single hull breach often meant total loss.

Structure solved the “localized failure” problem. But massive waves demanded yet another layer of defense: flexibility.

Extreme Engineering: Flexible Hulls and Layered Defense

Treasure ships were not rigid behemoths. Their design embraced dynamic adaptability.

The hull employed a double- or even triple-layer planking system: dense hardwoods like teak formed the outer shell to resist impact, while lightweight Chinese fir (Cunninghamia lanceolata) served as the inner load-bearing layer. Wood grains were laid in alternating directions to enhance crack resistance. Iron nails secured major joints, but critical seams retained slight gaps filled with tung oil putty—acting as a shock-absorbing buffer. This allowed the entire vessel to flex subtly in heavy seas, dissipating wave energy without fracturing—akin to the “ductile design” of modern earthquake-resistant buildings.

Propulsion was equally sophisticated: balanced rudders reduced steering effort; multi-masted junk rigs enabled sails to be raised or lowered independently, adapting instantly to shifting monsoons. In the early 16th century, Portuguese apothecary Tomé Pires wrote in his Suma Oriental: “Chinese ships are as steady as land—you can cook rice even in a storm.”

These were not exaggerations. They have been confirmed by both archaeological finds and digital simulations.

Archaeology and Simulation: From Quanzhou to Computer Models

In 1974, a Southern Song Dynasty ocean-going merchant ship (circa 1277) was excavated from Quanzhou Bay, Fujian Province. Its hull clearly preserved 12 watertight compartments, with bulkheads 12 cm thick. Chemical analysis confirmed the caulking contained tung oil and lime (Quanzhou Maritime Museum). This proves the technology predated Zheng He by over 150 years.

In the 21st century, researchers at Xiamen University used finite element analysis (FEA) to digitally reconstruct a Ming treasure ship. Simulations showed that under 8-beaufort seas (5.5-meter waves), watertight compartments reduced peak hull stress by 35%, dramatically improving survivability (Zhang et al., Journal of Nautical Archaeology, 2020).

Together, this evidence confirms: the “unsinkability” of Ming ships was no myth—it was a complete, replicable, and physically validated engineering system.

Conclusion: The Forgotten Pioneers of Naval Engineering

Today, every cargo ship, warship, and cruise liner features watertight compartments. The International Maritime Organization (IMO) mandates them as a core safety standard. Few remember that this lifesaving concept originated on the banks of China’s Yangtze River in the early 15th century.

Zheng He’s treasure ships were not monuments to imperial vanity. They were among the most sophisticated systems-engineering achievements of the pre-industrial world. By combining teak (for durability), nanmu (as a functional analog to oak), watertight bulkheads, flexible joints, and layered construction, Ming engineers built a maritime platform that operated at the very edge of physical possibility—yet remained virtually unsinkable.

As Joseph Needham observed:

“The Chinese achievements in shipbuilding constitute one of the most underestimated contributions to world civilization.”

— Science and Civilisation in China, Vol. 4, Part 3

This history reminds us: true technological leadership never relies on size alone—but on a profound understanding of materials, structure, and environment.

Frequently Asked Questions

Data and Authoritative Sources

- Treasure Ship Dimensions and Timber Records: Joseph Needham, Science and Civilisation in China, Vol. 4, Part 3 (Cambridge University Press)

- Quanzhou Ancient Ship Archaeology: Quanzhou Maritime Museum – www.qzsmuseum.cn

- Teak’s Durability: Schmidt, O. et al. (2018). Durability of Tropical Woods in Marine Environments. Wood Science and Technology, 52(3), 789–805.

- Introduction of Watertight Compartments in Europe: George F. Bass, A History of Seafaring (Thames & Hudson, 1977)

- FEA Simulation Study: Zhang, W. et al. (2020). Structural Analysis of Ming Treasure Ships. Journal of Nautical Archaeology, 49(2), 210–225.

- Portuguese Eyewitness Account: Tomé Pires, Suma Oriental (c. 1515), trans. Armando Cortesão (Asian Publishing House, 1990)